Human Flower Project

Monday, March 03, 2008

Chicory: The Root of Today’s Coffee Break

Jim Wandersee and Renee Clary provide a tantalizing trip through the Chicory underground, resurfacing in the French Quarter of New Orleans. All we’re missing are the beignets—and are we missing them!

Half-dollar-sized Chicory flower head consists of many individual petal-like flowers, squared-ended and toothed

Photo: Cirrus

By James H. Wandersee and Renee M. Clary

EarthScholars™ Research Group

Chicory, also known as Coffeeweed, Succory, and Ragged-Sailors, is a landlubber—a sky-blue member of the Aster (Asteraceae) family. Beautiful as Cichorium intybus (pronounced ”sigh-co’-ree-um inn’-ta-bus”) is, it’s not grown commercially for its flowers but as a salad foliage crop (radicchio) or as a root crop. Herein lies the “coffee connection”: this Chicory’s roots have been used for hundreds of years as a coffee substitute and a coffee additive— and to some people’s joy, it doesn’t contain any caffeine.

A Chicory root harvest

A Chicory root harvest

Photo: Chicory, S.A.

The root of the plant is cut, sliced, and kiln-dried, then roasted at 325 °F on a conveyor-type roaster and ground up to make commercially available “ground chicory root.”

A craving for “coffee with chicory” emerged in France. During that country’s civil war in the 18th century, coffee was scarce. The French found that roasted and ground chicory added body and flavor to the brew or, in a pinch, even substituted for coffee. The Acadians who journeyed from Nova Scotia brought this culinary delight and many other French customs to Louisiana. During the Union Naval Blockade of the War Between the States, coffee was unavailable, and New Orleanians added ground chicory to their coffee (in a 3:7 ratio) to stretch their unpredictable, precious, and expensive coffee supply. They liked how the coffee-chicory blend made their coffee darker, thicker, and what they termed “bittersweet.” To them, chicory powder not only added a complex flavor to coffee, it also somehow intensified it.

Café du Monde, New Orleans

Café du Monde, New Orleans

Photo: Cloud Travel

To this very day, you can depend upon the fact that a cup of café au lait served in New Orleans at its landmark, open-air coffeehouse, Café du Monde (open 24 hours a day, except on Christmas), will be made with rich, dark-roast coffee, ground chicory, and boiled milk—just as it was almost two centuries ago. New Orleans’ chicory coffee is seldom consumed black—it’s typically served mixed with 170°F milk (au lait) and paired with several hot beignets (“ ben-yays’ ”), a local delicacy—square, deep-fried French donuts dusted with powdered sugar. In Louisiana’s capital city of Baton Rouge, the popular coffeehouse most similar to Café du Monde is Coffee Call. Within the Crescent City and surrounding South Louisiana, coffee with ground chicory is sipped in greater quantities than anywhere else in the world.

Café du Monde’s signature coffee-chicory blend

Photo: mabjo

New Orleans is currently the number one coffee port in the country (unloading a quarter of a million tons of beans per year) and it clearly loves its coffee. In the mid- 19th century, the city boasted over 500 coffeehouses. All of them served coffee with chicory. They became places where business information was shared and were sometimes called “coffee exchanges” for that reason. We have New Orleans to thank for the work-day coffee break. As late as the 1920s, the coffee break had not yet become a part of the daily routine of American workers. But by 1928 in New Orleans, the mid-morning coffee break had become accepted as a hallmark of “The Big Easy’s” business practice and reflected a philosophy of life that included small pleasures.

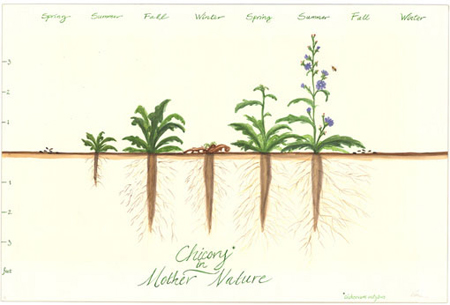

Wild Chicory is an easily recognizable roadside biennial. Sometimes this plant can even be weedy or invasive. Flowering occurs from June through September. The average plant produces about 3,000 seeds. It grows wild in all of the “lower 48” states, plus all of the Canadian provinces, and is partial to limestone soil.

The biennial life cycle of the Chicory plant

Photo: California Vegetable Specialties

The famous Swedish botanist and taxonomist Carolus Linnaeus used Chicory as one of the flowers in his floral Clock at Upsala (1751), because of the regularity with which its flowers opened and closed. Here in the US, Chicory flowers open about 6 a.m. and close around noon. A floral clock planted according to his principles is still flourishing at the University of Uppsala, where Linnaeus was a professor.

Beignets with at café au lait

Beignets with at café au lait

served at Café du Monde

Photo: Jeenybeen

If you find you are now insatiably curious about the Chicory plant, how would you like to visit one of the world’s Chicory museums? There are three—the Chicory Museum in Alholmen, Finland (housed in a former Chicory processing factory), the Chicory Museum in Geuzenberg, Belgium (focusing on Belgian endive, an edible blanched-leaf vegetable form of Chicory), and the Maison de la Chicore (housed within a family mansion) in Orchies, France. The latter is run by the Laroux family, the world’s number one Chicory root producer and processor today. Why not explore these unique travel possibilities while sipping a delicious cup of New Orleans-style café au lait?

Note: This article follows the practice of capitalizing the plant’s common name, but not capitalizing the name of its derivative commodity—namely, the ground powder or the name of the coffee blend.