Human Flower Project

Botanical Gardens, It’s Time to Make Our Case for Plant Research

James Wandersee and Renee Clary see the economics of botanical science changing. For plant research programs to survive within botanical gardens, they may need to show profits and/or make the benefits of their discoveries better known.

A Louisiana first-grader studying leaf structure

A Louisiana first-grader studying leaf structure

Photo: Vermilion Parish Schools

By James H. Wandersee and Renee M. Clary

EarthScholars™ Research Group

A recent Human Flower Project article entitled “Mr. Bromeliad Heads for Singapore,” presented the story of a famous Florida botanical garden that is losing some of its acclaimed research scientists, as that institution trims its budget and juggles multiple priorities. Recently, two of the garden’s orchid experts were dismissed, and now “Mr. Bromeliad,” Harry Luther, has left for a new job in Singapore.

The back-story source hyperlinked in the essay suggests that the garden’s current board is not principally interested in botany and considers plant science research to be tangential to its newly emphasized garden focus of engaging the public with plants—in aesthetic and utilitarian ways.

From a different perspective, one of the fired scientists put it this way: “Science, I think, intimidates the board. They don’t understand it; they don’t like it; they have no interest in it.” Another said, “I don’t think they see any value in the [botanical] research.” (quoted in Levey-Baker, 2010). As a result, the garden may have lost its hard-won, international scientific reputation as an orchid and bromeliad research center.

A plant science researcher at one of his study plots on native plant seed germination

Photo: Beacon Hill Park History

Research is important to botanical literacy and to the nation. Back in 1944, Vannevar Bush, Director of the US Office of Scientific Research and Development, began to plan for the future. Convinced that after WWII, the country still required ongoing support for research, Bush published “Science—The Endless Frontier” in March of 1945, outlining the importance and value of continued government funding for scientific study. Bush explained that scientific knowledge is derived from research, and a subset of that ever-growing body of knowledge is essential for the public to know and understand.

We think the central rationale for public understanding of plants may be found in the motto of London’s Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: “All life depends on plants.” This statement sets out the first of many reasons why we the people should know about plants.

The global scientific prominence of Kew across its 300 delightful acres can be credited to a series of enthusiastic plant collectors, visionary plant scientists, inspired landscape architects, and authoritative gardeners who, over three centuries, have grown and expanded the gardens, and the living and preserved collections they contain.

Linnaeus’ home alongside the former University of Uppsala Botanic Garden in Sweden, 2009

Photo: EarthScholars Research Group

As Linnaeus (1745) himself demonstrated in Uppsala, Sweden, botanic-garden-based research should drive and continually improve botany teaching. Linnaeus lived on the grounds of the garden where he carried out his studies, and he taught students on the second floor of his home. His wonderfully organized garden and adjacent house were the locus for his research and teaching.

Botanic gardens provide convenient sites for research, and their plant science researchers can help botanic gardens fulfill their mission of public education. Besides conducting basic research studies, plant scientists today increasingly provide related services to the garden’s visitors, plant aficionados, schools, commercial plant-related businesses, artists and photographers, government agencies, the scientific community, and even the cybersphere.

The Wellington Botanical Society’s CBD logo, promoting public understanding of plants

The Wellington Botanical Society’s CBD logo, promoting public understanding of plants

Image: Wellington Botanical Society

Our own science education research group has defined botanical literacy this way: It is the public’s understanding of a core set of pervasive plant science principles appropriate to making informed personal and societal decisions about plants in everyday life. In some of our studies, we have used the content of a representative sample of major U.S. newspaper news stories first to determine what kinds of plant-science-related information the U.S. public regularly encounters and then to help us to decide which botanical knowledge appears to be of greatest value to 21st-century citizens.

In 1998, the American Society of Plant Biologists (formerly ASPP) developed the following 12-item set of plant science principles which we have found very useful as criteria for anticipating what today’s public botanical knowledge core might contain.

Findings from our own botany education research studies have shown us that, especially in urban areas, the public only pays attention to and cares about the plants in their environment after a person or persons whom they respect help them to observe, identify, grow, interact with, and eventually, scientifically understand plants and their importance to human affairs as well as to the biosphere—and it’s best when such teaching takes place in personally meaningful and experiential ways. We’ve also hypothesized that the more botanically literate the public becomes, the greater its multifaceted interest in plants and the greater its support of botanic gardens, including plant science research. It is an astute conservation principle that the more we understand something, the more likely we are to value it and to want to preserve it.

The board of the Florida botanical garden that is terminating some of its plant science researchers seems to be saying that it wants to grow and display plants but doesn’t want to support botanical research—mainly for the reasons that (a) it is only marginally important to fulfilling the garden’s mission and (b) it can’t be justified as it doesn’t generate a substantial income stream.

While the first assumption above clearly seems misguided to us and worthy of a separate article, the second one may well be a defensible argument for a traditional institution under financial stress. Yet we believe it reflects 20th-century thinking in 21st century circumstances. Here are some alternatives we see.

Today, science and technology research models are changing. No longer are many research centers independently-supported or fully government-supported entities. Critical management skills in the new hyper-collaborative arenas of the global economy include the ability to transform the fruits of research into economic value. Botanic gardens, too, are forming alliances with other gardens, with businesses, industry, and academia. The conversion of their researchers’ expertise and their new findings to intellectual property is the process used by some innovative, budget-constrained botanic gardens to create assets that can ultimately be converted into economic value.

British scientist Michael Faraday (1710-1867)

British scientist Michael Faraday (1710-1867)

Image: University of Toronto

Basic research is indeed necessary for a field of science to progress, but, alas, few of its discoveries may have immediate economic value. A mix of basic and applied research can be more sustainable. When the great British scientist Michael Faraday, one of the giants who helped shape our current understanding of electricity and magnetism, was questioned by Chancellor Gladstone as to the use of this electricity he was working on, Faraday’s reply was, “I do not know Sir, but I wager that one day you will put a tax on it.” Faraday knew just how to satisfy his sponsor!

The support-me and leave-me-alone researcher of the past seems headed toward extinction. So does the I-am-so-famous-amongst-my-peers researcher. Salaries today are justified by sphere of responsibilities, economic productivity, and the number of clients served. Fewer and fewer research center scientists have the luxury of doing just basic research—seeking knowledge for knowledge’s sake. Currently, curiosity-driven research is less economically sustainable than is solution-seeking research. In times of economic contraction, sustainability and networking become the litmus tests of research center success. Innovation and income require that ideas, people, services, knowledge products, and physical products flow across institutional boundaries to and from allied gardens, companies, universities, and countries. Many research centers can no longer afford to be insular, independent, and externally funded—providing freely available services. We all must recognize that we are living in a time of profound change, and we can either bemoan that fact and pine for the return of the good old days, or we can adapt to our changing economic climate and implement new models to fund plant science research.

After all, plant research always pays off—although the specific time frame for that return-on-investment is unpredictable. Old scientific knowledge is sometimes untrustworthy, so contemporary research updates are often useful.

Garden rhubarb (Rheum x hybridum)

Garden rhubarb (Rheum x hybridum)

Photo: About

For example, during World War I, rhubarb leaves (Rheum x hybridum) were widely recommended to the public as a substitute for other greens unavailable in war-time. As a result, there were cases of acute poisoning and even some deaths. Researchers who investigated the plant found oxalates in all the organs of rhubarb plants—especially in the green leaves. There was some evidence that anthraquinone glycosides were also present. Scientists suspect leaf-poisoning may be a result of both biocidal compounds’ synergistic effects. The rhubarb stalks contain only low levels of oxalates and may be eaten safely. When poisoned from the rhubarb leaves, a person could experience weakness, burning in the mouth, difficulty breathing, burning in the throat, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, convulsions, coma, or death from cardiovascular collapse.

Poisonous leaves of Senecio vulgaris (not salad greens!)

Poisonous leaves of Senecio vulgaris (not salad greens!)

Photo: wiki

Here’s a closing example of the value of educating citizens, who then comprise a botanically literate and botanically observative public. In 2009, the German magazine Der Spiegel reported that a Hannover discount-chain supermarket customer noticed that packages of rocket salad greens (Eruca sativa) were, in fact, mislabeled. They also contained a poisonous plant with dangerous alkaloids as well! The potentially lethal poisonous plant, Senecio vulgaris, found all across Germany, has leaves that look quite similar to the otherwise-distinctive rocket salad greens. The tainted salad packet was determined to contain 2,500 micrograms of Senecio by University of Bonn botanical researcher Helmut Wiedenfeld. He told Der Spiegel that one microgram is the maximum amount a person can safely consume. The supermarket chain was fortunate this customer was “plant savvy,” recognizing the differences in leaf color and shape right away and sparing his liver and others’ from potentially life-threatening damage. Thanks to him, the stores quickly removed all the product from their shelves and nobody was harmed (as reported by Devins, The Local, 2009).

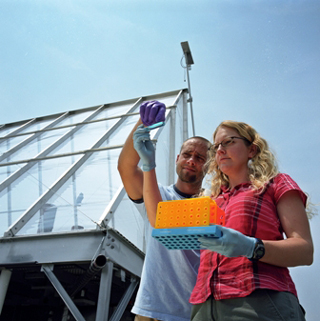

Researchers at the University of North Carolina—Chapel Hill

Researchers at the University of North Carolina—Chapel Hill

Photo: Sustainability, University of North Carolina

Our last point is that a botanic garden must interpret its own research and enlighten non-scientists if it expects the public to appreciate and support its work. We think the Missouri Botanical Garden does this well—beginning with these words of introduction to its visitors: “While most visitors discover a heightened appreciation and understanding of the world’s rich botanical heritage, few realize that beyond the floral panoramas and exhibits there exists another realm; our internationally renowned research enterprise. This is the “Unseen Garden.” Consider, too, this

“ title=” 21st-century description of the research”>21st-century description of the research conducted by the Missouri Botanic Garden.

Perhaps it’s time for all botanic gardens to make their unseen gardens visible and their research widely understood.

Comments

Excellent follow-up, Julie.I’ll try to keep you posted on the sad drama here in Sarasota.

Meanwhile, our thoughts are turning to spring in Turkey and one of our Turkish botanical colleagues compiling the first field guide to flowering plants of Lycia (SW Asia Minor). Stay tuned!

Holly (at) hollychase (dot) com

Unfortunately too many such governing boards are made up of well-meaning amateurs, and science is too intimidating, too boring, too expensive for them, so to cut corners research units are being trimed. After interviewing to be director of one of these gardens it was very clear that the trustees did not like my perspective although the garden staff seemed very supportive of my education and research ideas. Even worse, botany oftens fares very poorly in academic settings where it is an immersed minority in biology, and even worse than that, organismal botany has been shrinking at such a rate that it looked like botanical gardens would be the only botanical refuge. This is a grim scenario indeed.

The lesson presented in the salad story is very convincing!

Another option: Botanical gardens might consider framing their plant collections in terms of ecosystem services; their extensive planted areas could offset the costs of stormwater management and urban heat island reduction for the municipalities in which they are located.