Human Flower Project

Wednesday, May 03, 2006

Grow a Landmark: Wisteria

Some controversial flowers outlive their enemies.

Wisteria in bloom, Cinque Terre, Italy

Photo: Virginia Lohr, Washington State University

We think of flowers as here today, gone tomorrow: sped up versions of ourselves.

Then there’s wisteria. This strong, long-lived plant has been somewhat vexing (and overpowering) for gardeners. Maureen Gilmer‘s recent article unwinds several mysteries of the May bloomer: “Among seed-grown wisteria, some individuals may not flower for 20 years,” which by 21st century standards amounts to an eternity. (She suggests seeking out faster-performing varieties: “Big Johnny,” “Longissima,” “Issai Perfect,” and “Purple No. 1”.) Gilmer also describes, though does not recommend, some sadistic methods that gardeners have used to terrorize wisterias into hastier flowering.

It seems that those who aren’t rushing these plants into bloom with hatchets are chopping them down altogether. For all its vigor, wisteria is considered by some an invasive species. This article describes how Manhattan landscapers are struggling to coexist with the beautiful old Chinese wisterias (Wisteria sinensis) of Greenwich Village. “Wisteria vines can break glass, break windows, break wood,” says Neil Mendeloff (good thing Rudi Giuliani’s no longer mayor!). “It can be dangerous for homeless to sleep under,” Mendeloff says, because the big vines’ canopies can suddenly collapse under their own weight. “Moreover, wisterias are poisonous — two wisteria floribunda seeds can kill a child.”

Wisteria at Ashikaga Flower Park

Wisteria at Ashikaga Flower Park

Silk Road Lake

But there’s another approach to wisteria, one that savors its amazing patience, strength and longevity. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the wisteria is native to cultures that appreciate such qualities: China and Japan. This primer by Chris Beardshaw claims that the giant wisteria in Ushijima, Japan is “estimated at 1200 years old.” Knock yourself out with this portfolio of pictures from the Ashikaga Flower Garden, where big crowds enjoy the fuji blossoms every spring.

And we found a marvelous story from Shanghai Daily about the effort to relocate a 500 year old wisteria in the Minhang district. “The species is scarce in the city and this ancient sample makes it a treasure,” said Ye Xinlong, the local “green director.”

Ye persisted in a human flower project to move this plant that wound up costing thousands of hours and $8 million Yuan (USD $963,000). He spoke of the wisteria with respect and awe: “It has pulled through all the hard times and become a wordless historic witness. That makes it as worthy as anything to be protected…. We treat the old wisteria like a senior man who needs tender care.”

Even in the West, some wisterias have outlasted their detractors and become beloved landmarks. There are any number of “Old Wisteria” hotels and B&B’s that boast their wisteria vines as beautiful greeters. In our memory are planted the wisteria-covered arbor at University of North Carolina; we stumbled beneath that vine in the moonlight many an evening returning to Kenan dorm. And on a spring visit to D.C., in the fine company of Anne Ardery, we found the huge wisteria at Dumbarton Oaks in full bloom (Anne has a lovely wisteria in her own front yard in Louisville, too).

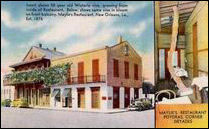

Maylie’s Restaurant, New Orleans

Maylie’s Restaurant, New Orleans

Photo: Ashleigh Austin

Both those vines are probably in bloom today, as is the famed wisteria at Ashikaga Flower Park in Japan. Just a few other wisteria landmarks of note include the vine at Grey’s Court in England, the biggie at New York’s Central Park, and we can only hope that Maylie’s Restaurant, New Orleans, is still going strong, with its wisteria vine coiling right up through the center of the dining room. Such plants seem to have exceeded the evanescence we associate with flowers: they’ve become citizens emeriti—important presences on the local scene.

A final twist of wisteriana: we have learned from Berkeley horticulturist Margaret that Chinese (sinensis) and Japanese (floribunda) wisterias can be easily distinguished by noticing “what direction the vines are twining. Wisteria floribunda, the Japanese Wisteria, twines clockwise (picture forming the letter J, for Japan), while the Chinese Wisteria twines counter-clockwise (picture forming the letter C, for China).”

So why is the venerable Ashikaga plant turning counterclockwise? Because the Japanese are especially fond of their “Chinese gardens.”

Culture & Society • Gardening & Landscape • Secular Customs • Travel • Permalink