Human Flower Project

Sunday, May 03, 2009

Kew: A Horticultural Education

Allen Bush double-dug his beginnings as a plantsman; three decades ago, he was an International Trainee at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Alpine House, Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew

Photo: Martin Hamilton

Thirty years have gone by in the blink of an eye and, suddenly, the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, England, is celebrating its 250th anniversary. I slogged around Kew in 1979, deliriously happy with the gardens and history around me. I count my lucky stars. As a lowly International Trainee, way down the pecking order, I was thrilled to have a shot at doing Her Majesty’s service in Wellingtons—and getting an education to boot.

The 300-acre gardens at Kew, along the River Thames, upstream from London past Putney and Barnes, began as a royal getaway and grew into a powerful botanic preserve. Along the way the Kew’s Director Joseph Banks, in 1787, engaged Captain Bligh in what turned-out to be high-seas infamy, and by the early 20th century Kew plant collectors had gathered rubber tree seeds in the South American rain forest, unwittingly turning a boom into a bust.

Captain Bligh’s breadfruit cargo was tossed overboard, 1789, but rubber tree seed from other Kew collecting expeditions made the trip back to England

Etching: Robert Dodd, via wiki

Bligh’s collection of breadfruits got thrown into the Pacific, with the Mutiny on the Bounty, but collected seeds of wild Brazilian rubber trees made it to England. They were propagated at Kew, exported to Ceylon, and grew so well that the ensuing overproduction in Malaysia and the Dutch East Indies burst the economic bubble in the Amazon basin, that had grown so dependent on its native species. It took massive rainforest deforestation before the Brazilian government forgave the injury; by the late 1970s Brazil desperately needed Kew’s expert botanic involvement to help catalog uncharted tropical species.

Director of students Leo Pemberton, a brilliant educator but an impossibly disorganized administrator, greeted the students and trainees in the so-called melon yard behind the Jodrell Laboratory in late August 1978. Standard issued Wellington boots and donkey jackets were handed-out. I was introduced as a colonist and Pemberton facetiously pointed-out that King George III had spit watermelon seeds where I was standing. Pemberton’s mind often wandered. He took me aside a little later and asked whether I was here for one or three years. No one seemed to know, he said. I assured him that I had applied and been accepted – in a letter signed by him—for one year. In spite of constantly grumbling students and trainees, Pemberton’s regime produced remarkably well-trained gardeners.

I arrived with a working knowledge of Max Weber and Karl Marx that didn’t help me a bit with cellular meiosis. Even with a sociology degree and several years under my belt as a jackleg landscaper, I was in way over my head compared to the three-year Kew Diploma students—precocious young horticulturists—who had been accepted after years of practical training and rigorous schooling in natural history. I tried not to embarrass myself, but I had painstakingly avoided the slightest hint of science since high school biology.

When I find myself in the company of scientists, I feel like a shabby curate who has strayed by mistake into a room full of dukes.

W.H. Auden

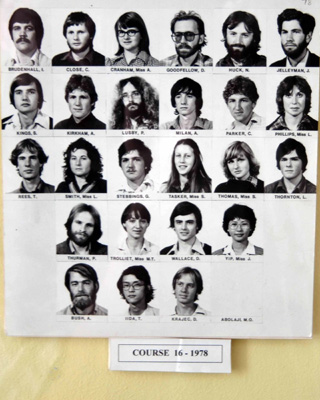

Kew incoming class 1978; find author Allen Bush on the bottom row, left

Kew incoming class 1978; find author Allen Bush on the bottom row, left

Photo: Martin Hamilton/Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew

I was accepted to Kew as an International Trainee simply because The Kentucky English Speaking Union had the 2nd largest chapter in the world in 1978, trailing only London. Josh Everett, a retired banker and zealous Anglophile, had made it happen. The British Empire was Everett’s megachurch, and the Kentucky E.S.U. his franchise. He drummed-up hundreds of local members who enjoyed attending periodic lectures on odd things English, or pretended because Mr. Everett cared. They also graciously raised money for scholarships and wrote letters on behalf of starry-eyed students who wanted to study in England. I was accepted to tend the hallowed Kew grounds for a year for no good reason. (My family fortunes with the E.S.U. didn’t end here. My daughter Molly won their 1998 Kentucky Shakespeare Competition and traveled to New York’s Lincoln Center and finished 4th in national competition. She had a good bit more talent.)

The trainees jumped in with the first-year diploma students, who began their Kew careers with an intense block of classes: three and one-half months of taxonomy, plant physiology and pathology, before being turned-out into the garden for the next year. They returned in January for the 2nd year block, completing the routine of sciences, garden design, construction, and management studies in the summer of their third year. I could pick and choose classes from among this three-year offering. I spent Saturday mornings in the herbarium library overlooking the Thames, or wandering the garden, studying in the Palm House, Order Beds, Temperate or Alpine Houses for plant identification tests. Stinky voodoo plants, fussy Juno Iris and alpine gentians so blue were all new and exquisite.

The students organized a popular public lecture series called The Kew Mutual Improvement Society. Beth Chatto’s presentation of perennials is unforgettable. The successful nurserywoman, and ten-time Gold Medal winner at the Chelsea Flower Show, is a gifted speaker and writer. She pulled individual flowers from a bucket hidden behind a lectern, snipped earlier from the nearby Order Beds, and then threw several balls in the air at once – describing the plant, its growing habits, and its prefect garden companion – before placing each stem in a vase. She continued adding stems until the clever sleight of hand could hide no more – an exuberantly crafted floral arrangement. The Kew students could draw stars like Chatto and garden designer Russell Page, author of Education of a Gardener, because this was a hot bed of the plant world. Chatto and Page appreciated the students’ efforts. (I was very pleased to see the Kew Mutual had invited Landscape Architect Martha Schwartz this past March. Her 1979 Boston townhouse bagel garden design, a wonderful spoof couched in humdrum architectural jargon, stirred-up the staid profession and set her sailing on a very innovative career.)

The Alpine House and Rock Garden, Kew

The Alpine House and Rock Garden, Kew

Photo: Martin Hamilton

I was rotated around the gardens, first serving in the South Arboretum near the Japanese pagoda tending a heather garden, then moving to the North Arboretum where I shuffled around the rose beds behind the Palm House before taking a turn in the “temperate pits”—sowing seeds and cleaning pots with a smelly solvent. The students and trainees were a very ambitious and hardworking lot who overcompensated for permanent staff that was – at the time—a mixed bag (a shovel can be a handy tool to lean on).

During this time of national labor unrest, growing unemployment and rising inflation, the garden managed comfortably with financial largesse from the Ministry of Agriculture. Margaret Thatcher was elected Prime Minister in May 1979, and the new fiscal austerity meant that Kew would soon begin charging – out of necessity and amidst public outcry – more than the traditional penny entrance fee to cover a portion of its expenses. Its 1,200,000 visitors brought in a paltry £12,000 ($25,000) in 1979 – enough to keep the students and trainees in Wellies and Donkey Jackets, with a little left over for massing lavish bedding schemes in front of the Palm House. Now, like most public gardens, Kew charges an admission (£13 / $19.20) and has gift shops and restaurants; the gardens are run like a business to survive.

Kew’s global conservation work continues to expand

Photo: Martin Hamilton

And though governments may have looked upon gardens and botanic research as frivolous extravagance, the British now understand the scientific imperative of ecological salvation and support partnerships with the Millennium Seed Bank at Kew’s satellite garden at Wakehurst Place in West Sussex. Already, one billion seeds are safeguarded, in cooperation with other local seed banks, and Kew is headed toward a goal of preserving 24,000 species by 2010. The days of imperial callousness are over – botanically, at least. Kew, now, mercifully looks over the planet. Kew was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2003.

One of Kew’s current objectives is: “Building a global network to restore damaged habitats.” In the foreword to Allen Paterson’s The Gardens at Kew, a sumptuous new coffee table book, Stephen D. Hopper, now director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, writes, “At no other point in history have plants been so critical to sustainable life on earth.”

Kew students and trainees, Fall 1978, Wakehurst Place, West Sussex

Photo: Allen Bush

I love Kew and wonder, sometimes, if another four seasons, like those thirty years ago, might be in the cards. My prayers go out, in hopes that – somehow—I might be fortunate again to double-dig planting beds in the sandy soils along the Thames. If I am twice blessed, I promise I won’t come back late from Friday pub lunch on Kew Green.

Culture & Society • Gardening & Landscape • Politics • (0) Comments • Permalink