Human Flower Project

To Paint Two Roses

An artist in Cambridge, Massachusetts, sets out on a new subject. With Manet to help him over triviality-block, Nick Read finds flowers “obstinate” and glorious.

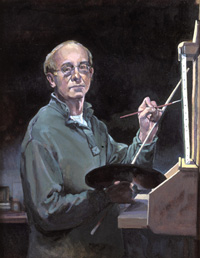

Self-portrait, by Nicholas Read

Self-portrait, by Nicholas Read

By Nicholas Read

When a friend asked me recently to describe what it was like to paint flowers, I had no ready response. I am a painter, but the subjects I choose do not include flora. Nothing against it, but the question caused me to wonder whether flower painting Is different from painting, say, the Maine shoreline, a pretty young woman, a dog, a horse, a ship, or any of thousands of possible subjects?

This is what I found out.

A trip to Google brought me immediately to “Painting Flowers.” The BBC teamed up with the National Gallery and public galleries across the UK to create this unique online art exhibition of flower paintings. They were joined by the Royal Horticultural Society—“ to explore the vivid theme of flower painting in art.”

The site includes interesting information. For example, flower painting is over 3500 years old: paintings of lilies dating from 1580 BCE were found in a villa in Crete. The figure of Flora in Botticelli’s famous painting in the Uffizi, Primavera, strews identifiable flowers over the garden on which she walks (as discussed, for example, in Levi d’Ancona, Botticelli’s “Primavera”: A Botanical Interpretation, Olschki, 1983).

The intensity of van Gogh’s sunflowers reflects innovation in the fabrication of artists’ pigments, notably the introduction of chrome yellow. (By the late 19th century, the vibrant yellow was one of a series of new and exceptionally vivid colors. Chrome yellow is actually a lead salt, lead chromate (PbCrO4). The pigment is still used today but it has been replaced in many cases by similarly colored, less toxic organic pigments. Unfortunately chrome yellow degrades over time; van Gogh’s once brilliantly glowing sunflowers, for example, now appear to be dry, drab ocher shadows.)

Branche de pivoines blanches et secateur (1864)

Edouard Manet

Photo: Musee d’Orsay

But what about actually painting a picture of flowers? How does one get started? Which flowers does one choose? Coral Guest, a contemporary British artist featured on the BBC website, describes it this way:

“You can simply pick the plant up, put it in front of you, and say “All right, that’ll do,” or you can look and turn and experiment and sketch and find within that flower an arrangement which has a kind of naturalistic appeal which says something about the real character, the real personality, real demeanor of that subject that you are looking at.

“When you do look at the plant in that way, you find that as you look between the leaves and stem and the angle of the flower, what you get is a particular, almost an arabesque shape. When that’s placed on a white page, you have to consider those shapes in between the parts of the plant because the whole thing holds together as one. And this happens almost intuitively when the artist finds the right place or the right way to display the plant on the page. It can be the difference between someone looking at something and being interested and looking at something and being amazed by it.”

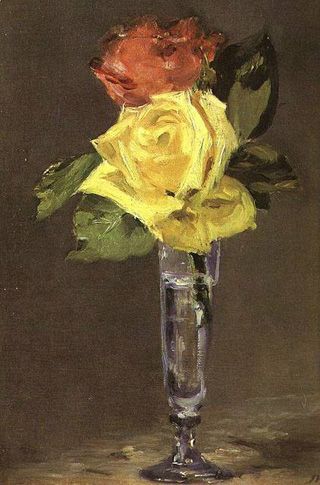

Des Roses dans un Verre à Champagne (1882)

Des Roses dans un Verre à Champagne (1882)

Edouard Manet

Photo: SCVRS

I looked at many pictures of flowers from my own library such as Flower Painting (Robin Harris, Phaidon, 1976). And I looked again at the Internet. A listing for the Santa Clarita Valley Rose Society’s “Roses In Art” webpage describes the history of rose painting. It says that the 19th century was the heyday of rose painting, noting a fine example in the Glasgow Museum’s Burrell Collection, called A Pink Rose and a Yellow Rose or, alternatively, Des Roses dans un Verre à Champagne . It was painted by the French artist, Édouard Manet in 1882, the year before his death.

Manet was seriously ill with a rare nerve disorder when he painted Pink Rose/Yellow Rose. He painted some seventeen flower still-lifes, including this one, in the two years before he died at age 51. Many of these small paintings show oeillets (carnations), pensées (pansies), lilacs, peonies, tulips, pinks, clematis and roses, most of which were brought as gifts to the artist by his friends. These paintings probably did not require too much of Manet’s failing energy and they gave the artist “enormous pleasure.” They are lovingly reproduced, together with tributes by Manet’s friends, in The Last Flowers of Manet (Robert Gordon & Andrew Forge, Abrams, 1986)

I find it gratifying to think that Manet’s debilitating illness was the genesis of his flower painting. It strips the genre—in this case at least—of any hint of triviality or preciousness. The flowers he painted were given to Manet by caring friends when he was a semi-invalid. One writer described the scene this way:

“He was sitting up in bed, painting flowers—the gifts of his visitors—in glass vases, pinks, roses and clematis in water, which combined the limpid lucidity of Vermeer’s paintings of stems in water with his own unmistakable thick, creamy brush strokes. …These were his last masterpieces, fragile impressions of refracted colour and light.” (Sue Roe, The Private Lives of the Impressionists: Harper Collins, 2006), pp. 246-47). Not only was Manet able to paint flowers, but he was also able to derive great enjoyment—and, I would add, dignity—from the exercise.

Manet’s last days cannot have been easy. He died of tabes dorsalis caused by untreated syphilis and rheumatism, which he had contracted in his forties. The disease caused him considerable pain and partial paralysis due to a slow degeneration of the nerve cells and nerve fibers that carry sensory information to the brain. Toward the end, his left foot was amputated because of gangrene; eleven days after the operation Manet died.

Pink Rose/Yellow Rose was purchased by the Scottish shipping magnate Sir William Burrell in 1937 and, as part of Burrell’s art collection, was donated in 1944 to the City of Glasgow. Burrell donated money for a gallery as well, but he was concerned that urban air would adversely affect the collection. On account of delays finding an appropriate rural site, the collection was not permanently displayed until the 1970s.

The painting is a modest 13 1/2” by 9 5/8” (34.2 x 24.8 cm.) Manet has posed a crystal flute vase in which are placed a pink rose and a yellow rose, against a neutral greyish-blue background. According to the Glasgow Art Museum’s catalog, his “painterliness is evident in the broad brushstrokes he uses to convey the forms of the petals and the leaves.”

If the heyday of flower painting was the 19th century, and if Manet was a serious practitioner of the genre—to the point even of providing relief from a progressive, fatal disease—what better way to understand the challenge and the reward of painting flowers than by walking in the artist’s footsteps? To do this it is not necessary to copy or even imitate Pink Rose/Yellow Rose, but merely to start where Manet started: using the elements of his painting—the vase, the pink rose, the yellow rose, rose leaves and a neutral background—as the building blocks of a painting.

I cannot leapfrog over Coral Guest’s hurdles; my vase, my flowers and my background will not be the same as Manet’s, so I will still have to “consider … shapes in between the parts of the plant because the whole thing holds together as one.”

Nick’s model

Nick’s model

Photo: Nicholas Read

So I bought a similar vase at the local Goodwill. I went to the florist in Central Square and showed Mariou, the saleswoman there, Manet’s painting and said I wanted flowers the same as those pictured. Mariou sold me two roses, but said that it might be a day or two before they would be as open as the flowers in the painting (although you can, she added, accelerate opening by putting the flowers into warm water).

I brought all this back to my studio and set up the painting.

That’s when I started having problems. While I had elements of the Manet painting, the flowers were not the same size, not exactly the same color, and were not open in the same way; their leaves were configured altogether differently than those Manet painted. Try as I might, I could not contort the elements into a tableau of Pink Rose/Yellow Rose.

I then remembered that I had set out to do a painting of flowers, not a painting of a painting. I’m sure Manet would have said, let the flowers do what they will. It’s not about the result, but about the doing. Freed from the mistaken goal of copying, I could “look between the leaves and stem and the angle of the flower, [to the] particular, almost an arabesque shape.”

Nick’s painting, stage one

Nick’s painting, stage one

Photo: Nicholas Read

For me a painting is a two step process. First, I need to understand and set down in a general way the structure of the subject (which includes the darks and lights). Second, I need to understand and capture the surface (or color) of the subject. If I were merely copying the painting Pink Rose/Yellow Rose, Manet would have already taken the first step for me. A painting is two-dimensional; its structure has already been committed to a flat surface. But the buds of the roses, their stems and leaves, the vase, the water in it, and the surface on which they all sit are three dimensional objects. It is up to the painter to describe them in two dimensions.

Having set up the vase and flowers in my studio as shown in the photograph, I start to paint. On the first day, I lay in the basic composition, including the lights and darks that define the shape and structure of the forms, leaving off the yellow rose for the time being in the hope that it would open in a way that would be at least similar to that in Manet’s painting.

Waiting was not a solution, however. Flowers in a vase are already dead; water, light and temperature only keep them looking alive. After a day or so, waiting for a hoped for metamorphosis didn’t seem like a good idea. The bloom was opening (slowly), but the leaves were starting to go limp! So I proceeded with what I had. (I should have done this to begin with!)

Stage two

Stage two

Photo: Nicholas Read

The second is step is interpreting the surfaces. There are many. The rose petals are translucent and fine, with intense color and subtle shadow—very much like a baby’s face. The leaves are opaque, but they are veined and waxy. There is the vase also, with its smooth and patterned surfaces. And there is the background—artificial to be sure, but a means by which to focus the viewer and eliminate distracting details.. These elements all combine and contract to make a visually interesting composition and, hopefully, evoke something of the spirit of a vase of flowers.

But in painting these colors and textures, I ran up against a second problem: try as I might, I could not seem to capture the intense translucence of the roses in oil paint. For my pinks I would mix cadmium red, vermilion, scarlet lake, alizarin crimson and rose madder with white to come up with the elusive pink, whose shadows were purple, green and red. The yellows were challenging too. No combination—cadmium yellow light, cadmium yellow deep, cadmium orange, Naples yellow and yellow ochre—could evoke the intensity of the yellow rose, and the petals’ capacity to transmit light.

It is always a good idea when confronting a painting problem to see how other painters have handled a similar problem. I went to the library and checked out three books: Josephine Walpole, A History and Dictionary of British Flower Painters 1650-1950 (Antique Collectors’ Club 2006); Peter Mitchell, European Flower Painters (Adam & Charles Black 1973); and Wilfred Blunt, The Art of Botanical Illustration (Antique Collectors’ Club and Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew 1950). I also visited the nearby Boston Museum of Fine Arts. The MFA did not have many flower painting on display that day, but I was able to see a variety of solutions adopted by such artists as van Huysum, Gainsborough, Burne Jones, Fantin Latour, Alma Tadema, Dewing, LaFarge, Gaugin and Renoir. Paintings not on display but appearing on postcards in the museum shop included those by Heade, Hills, Redon and Matisse.

I was surprised by what I saw. Each example was expert, insightful, gifted and elegant, but very little of it came close to capturing the characteristics of a flower that has so baffled me. It was the light. It wasn’t there. I look again at the photograph. The same.

I imagine it is because paint and printing ink are opaque. When light meets the surface of the paint, it stops. The paint cannot emit light. Certain techniques will suggest the emission of light. The watercolors in the book I looked at, for example, captured the incandescent quality of flowers better than the oils. This is because watercolors, when applied in a wash, allow the light to pass through the paint and refract off the white paper and back to the viewer, resulting in an impression of luminosity. Oil paints can be applied in this way but the medium is inherently heavier and darker, so the same lightness is difficult, if not impossible to achieve. The old masters obtained a glow through the use of glazes. Thin layers of transparent color are applied so that the light passes through them to reflect off the under painting below. Most modern painting—including that of Manet—was painted all prima, however. That means that the artist has identified the color and matched it (or rendered his “impression” or it), and the identified colors collectively created an image with structure and light.

Aware now of these limitations (and feeling less inadequate), my painting moved quickly to completion.

Finis

Finis

Photo: Nicholas Read

All I can now say is that it represents my best effort to capture what I see before me. A flower painting is unique because of the intensity and type of color required, very different from that of, say, a dog or a ship. Even looking at different reproductions of Pink Rose/Yellow Rose, I never came to a clear understanding of what the colors in fact are. They were sometimes too yellow, something too dark, sometimes garish, sometimes mute. One would have to go to Scotland, I suppose, to identify them with any certainty.

But even then, would they be the same as the colors Manet painted? Color is not immutable. I recently looked at the glass flowers at the Harvard Museum of Natural History. As ingenious as they were, I was struck by how little life they had. Apparently they were for many years exhibited in natural light. This had probably faded them. Or maybe they were always that way. As has been suggested, even van Gogh’s flowers are less yellow today than they were a century ago.

Flowers are obstinate. They defy capture. They remain completely autonomous and unique, and cannot be reproduced in paint , glass, or even in words. Their moment of glory is also fleeting, and in that way became a representative of life itself. And that, I think, is the source of their allure.

And why a dying man might be drawn to them.

To capture so elusive a subject is a challenge indeed, and makes the words of John Ruskin completely understandable: “If you can paint one leaf you can paint the world.” (5 Complete Works, “Of Leaf Beauty”: Bryan, Taylor & Co. 1894, p. 61).

I read spellbound. Nick, the combination of text and images really conveyed your process.