Human Flower Project

Search Results for:Kew

Kew 1978 A Horticulcutral Education

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Sunday, May 03, 2009

Kew: A Horticultural Education

Allen Bush double-dug his beginnings as a plantsman; three decades ago, he was an International Trainee at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Alpine House, Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew

Photo: Martin Hamilton

Thirty years have gone by in the blink of an eye and, suddenly, the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, England, is celebrating its 250th anniversary. I slogged around Kew in 1979, deliriously happy with the gardens and history around me. I count my lucky stars. As a lowly International Trainee, way down the pecking order, I was thrilled to have a shot at doing Her Majesty’s service in Wellingtons—and getting an education to boot.

The 300-acre gardens at Kew, along the River Thames, upstream from London past Putney and Barnes, began as a royal getaway and grew into a powerful botanic preserve. Along the way the Kew’s Director Joseph Banks, in 1787, engaged Captain Bligh in what turned-out to be high-seas infamy, and by the early 20th century Kew plant collectors had gathered rubber tree seeds in the South American rain forest, unwittingly turning a boom into a bust.

Captain Bligh’s breadfruit cargo was tossed overboard, 1789, but rubber tree seed from other Kew collecting expeditions made the trip back to England

Etching: Robert Dodd, via wiki

Bligh’s collection of breadfruits got thrown into the Pacific, with the Mutiny on the Bounty, but collected seeds of wild Brazilian rubber trees made it to England. They were propagated at Kew, exported to Ceylon, and grew so well that the ensuing overproduction in Malaysia and the Dutch East Indies burst the economic bubble in the Amazon basin, that had grown so dependent on its native species. It took massive rainforest deforestation before the Brazilian government forgave the injury; by the late 1970s Brazil desperately needed Kew’s expert botanic involvement to help catalog uncharted tropical species.

Director of students Leo Pemberton, a brilliant educator but an impossibly disorganized administrator, greeted the students and trainees in the so-called melon yard behind the Jodrell Laboratory in late August 1978. Standard issued Wellington boots and donkey jackets were handed-out. I was introduced as a colonist and Pemberton facetiously pointed-out that King George III had spit watermelon seeds where I was standing. Pemberton’s mind often wandered. He took me aside a little later and asked whether I was here for one or three years. No one seemed to know, he said. I assured him that I had applied and been accepted – in a letter signed by him—for one year. In spite of constantly grumbling students and trainees, Pemberton’s regime produced remarkably well-trained gardeners.

I arrived with a working knowledge of Max Weber and Karl Marx that didn’t help me a bit with cellular meiosis. Even with a sociology degree and several years under my belt as a jackleg landscaper, I was in way over my head compared to the three-year Kew Diploma students—precocious young horticulturists—who had been accepted after years of practical training and rigorous schooling in natural history. I tried not to embarrass myself, but I had painstakingly avoided the slightest hint of science since high school biology.

When I find myself in the company of scientists, I feel like a shabby curate who has strayed by mistake into a room full of dukes.

W.H. Auden

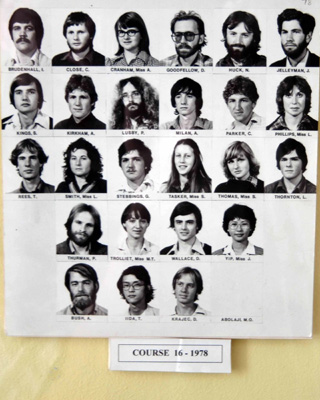

Kew incoming class 1978; find author Allen Bush on the bottom row, left

Kew incoming class 1978; find author Allen Bush on the bottom row, left

Photo: Martin Hamilton/Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew

I was accepted to Kew as an International Trainee simply because The Kentucky English Speaking Union had the 2nd largest chapter in the world in 1978, trailing only London. Josh Everett, a retired banker and zealous Anglophile, had made it happen. The British Empire was Everett’s megachurch, and the Kentucky E.S.U. his franchise. He drummed-up hundreds of local members who enjoyed attending periodic lectures on odd things English, or pretended because Mr. Everett cared. They also graciously raised money for scholarships and wrote letters on behalf of starry-eyed students who wanted to study in England. I was accepted to tend the hallowed Kew grounds for a year for no good reason. (My family fortunes with the E.S.U. didn’t end here. My daughter Molly won their 1998 Kentucky Shakespeare Competition and traveled to New York’s Lincoln Center and finished 4th in national competition. She had a good bit more talent.)

The trainees jumped in with the first-year diploma students, who began their Kew careers with an intense block of classes: three and one-half months of taxonomy, plant physiology and pathology, before being turned-out into the garden for the next year. They returned in January for the 2nd year block, completing the routine of sciences, garden design, construction, and management studies in the summer of their third year. I could pick and choose classes from among this three-year offering. I spent Saturday mornings in the herbarium library overlooking the Thames, or wandering the garden, studying in the Palm House, Order Beds, Temperate or Alpine Houses for plant identification tests. Stinky voodoo plants, fussy Juno Iris and alpine gentians so blue were all new and exquisite.

The students organized a popular public lecture series called The Kew Mutual Improvement Society. Beth Chatto’s presentation of perennials is unforgettable. The successful nurserywoman, and ten-time Gold Medal winner at the Chelsea Flower Show, is a gifted speaker and writer. She pulled individual flowers from a bucket hidden behind a lectern, snipped earlier from the nearby Order Beds, and then threw several balls in the air at once – describing the plant, its growing habits, and its prefect garden companion – before placing each stem in a vase. She continued adding stems until the clever sleight of hand could hide no more – an exuberantly crafted floral arrangement. The Kew students could draw stars like Chatto and garden designer Russell Page, author of Education of a Gardener, because this was a hot bed of the plant world. Chatto and Page appreciated the students’ efforts. (I was very pleased to see the Kew Mutual had invited Landscape Architect Martha Schwartz this past March. Her 1979 Boston townhouse bagel garden design, a wonderful spoof couched in humdrum architectural jargon, stirred-up the staid profession and set her sailing on a very innovative career.)

The Alpine House and Rock Garden, Kew

The Alpine House and Rock Garden, Kew

Photo: Martin Hamilton

I was rotated around the gardens, first serving in the South Arboretum near the Japanese pagoda tending a heather garden, then moving to the North Arboretum where I shuffled around the rose beds behind the Palm House before taking a turn in the “temperate pits”—sowing seeds and cleaning pots with a smelly solvent. The students and trainees were a very ambitious and hardworking lot who overcompensated for permanent staff that was – at the time—a mixed bag (a shovel can be a handy tool to lean on).

During this time of national labor unrest, growing unemployment and rising inflation, the garden managed comfortably with financial largesse from the Ministry of Agriculture. Margaret Thatcher was elected Prime Minister in May 1979, and the new fiscal austerity meant that Kew would soon begin charging – out of necessity and amidst public outcry – more than the traditional penny entrance fee to cover a portion of its expenses. Its 1,200,000 visitors brought in a paltry £12,000 ($25,000) in 1979 – enough to keep the students and trainees in Wellies and Donkey Jackets, with a little left over for massing lavish bedding schemes in front of the Palm House. Now, like most public gardens, Kew charges an admission (£13 / $19.20) and has gift shops and restaurants; the gardens are run like a business to survive.

Kew’s global conservation work continues to expand

Photo: Martin Hamilton

And though governments may have looked upon gardens and botanic research as frivolous extravagance, the British now understand the scientific imperative of ecological salvation and support partnerships with the Millennium Seed Bank at Kew’s satellite garden at Wakehurst Place in West Sussex. Already, one billion seeds are safeguarded, in cooperation with other local seed banks, and Kew is headed toward a goal of preserving 24,000 species by 2010. The days of imperial callousness are over – botanically, at least. Kew, now, mercifully looks over the planet. Kew was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2003.

One of Kew’s current objectives is: “Building a global network to restore damaged habitats.” In the foreword to Allen Paterson’s The Gardens at Kew, a sumptuous new coffee table book, Stephen D. Hopper, now director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, writes, “At no other point in history have plants been so critical to sustainable life on earth.”

Kew students and trainees, Fall 1978, Wakehurst Place, West Sussex

Photo: Allen Bush

I love Kew and wonder, sometimes, if another four seasons, like those thirty years ago, might be in the cards. My prayers go out, in hopes that – somehow—I might be fortunate again to double-dig planting beds in the sandy soils along the Thames. If I am twice blessed, I promise I won’t come back late from Friday pub lunch on Kew Green.

Culture & Society • Gardening & Landscape • Politics • (0) Comments • Permalink

Botanical Gentry Make Room For Pokeweed

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Friday, July 13, 2007

Botanical Gentry, Make Room for Pokeweed

As the unruly “salat” maker vies for space in her garden, horticulturist and garden designer Jill Nokes puts in a good word for a disparaged plant. Jill, we and the mockingbirds thank you!

Pokeweed in flower, Austin, TX, July 2007

Photo: Jill Nokes

By Jill Nokes

Around here, the summer of ’07 will surely be remembered for freakishly abundant rainfall. It’s already mid-July, yet my garden looks more like Vietnam’s Mekong Delta than Central Texas. But after two years of scary drought conditions, I’m not complaining. Even ordinary plants are super-sized and showing off, hoping to get a full-time gig in the permanent display. I’m especially enjoying a bumper crop of pokeweed (Phytolacca Americana var. Americana).

Pokeweed

Pokeweed

Phytolacca Americana var. Americana

Photo: Jill Nokes

Pokeberry and elderberry are among the plants that fall into the red-headed stepchild category: they are interesting, and even useful, but for most people they are just too unruly or free-spirited to mingle well with the botanical gentry. Horticultural literature in general disdains them and insists that every serious gardener must learn to separate the sheep from the goats when making plant selections. But, I wonder, why must it be an either/or proposition? Many rejected plants are well suited for remnant, overlooked and underused areas in the yard, like alleys or the narrow space between a garage and fence, where the trash cans are kept. There, they can grow freely and be enjoyed for what they are.

Pokeweed (also called pokeberry) is a large-leaved branching plant with reddish stems and long clusters of small white flowers that develop into dark purple-black fruits. It freezes back to a perennial rootstock, and also enlists avian assistance in seed dissemination. As with other berry-producing plants such as chile pequin, lantana, and possum-haw holly, mockingbirds are crazy about the fruit. Recently I read that the population of many common songbirds was dropping, so I believe I’ll leave those extra plants where they are for now.

Preparing poke salad

Preparing poke salad

near Marshall, TX, c. 1930

Photo: via answers.com

Folklore tells us that pokeweed or poke salad, like early spring dandelion and chicory, was a welcome addition to a pioneers’ winter-weary salt pork diet, though one is warned to boil only the young greens from shoots no longer than six inches long, before the stems turn crimson, because the older plant has toxic properties. You must “throw off” the boiling water twice before eating. One of pokeweeds “reputed virtues” is as a cathartic—I believe I’ll leave the taste testing to my mockingbirds.

Someone once told me that during the Civil War, soldiers used the purple stain from the fruit as an ink substitute. I wonder if those pokeweed letters are still legible, or if they have faded into the ground like the plant itself after the first frost. Pokeweed’s range is so widespread, that I like to imagine hungry and lonesome soldiers happy to recognize it as they were bivouacked in temperate forests far from home.

Widely Winged

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Friday, February 03, 2012

Widely Winged

After years of assiduous transnational work, botanists at Kew coax an iris into bloom for the first time.

Iris stocksii bloomed in cultivation for the first time 1/23/12, at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew.

Photo: Andy McRobb

We imagine Tony Hall swinging through the door of a hospital maternity ward: “It’s an Iris stocksii!”

Congratulations to Tony, to Kit Strange, Juan Piek and everyone else involved in finding the rare bulbs in Afghanistan and handling them with such wisdom and care that the first flowered last month at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. (And our thanks to Allen Bush for informing us all along the way.)

We are delighted and grateful to post in full Tony Hall’s fine description of this beautiful flower, its “gestation” and birth. A more complete scientific description may be found here.

If you’ve ever wondered how a top notch working horticulturist thinks (hyper-observant, meticulously historical), this account is revealing. (We’ve taken the liberty of dividing Hall’s four paragraphs into shorter passages for ease of reading online.)

With Wreaths

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Monday, May 30, 2005

With Wreaths

Why do circular flower arrangements mean “in memoriam”?

Memorial Day and Halloween are the only two dates on the calendar when U.S. citizens admit to death. The other 363 days a year, we’re getting ahead, we’re working out with weights. We’re just fine!

Keven Outman

Keven Outman

at the grave of

Lt. Michael Joseph Blassie

St. Louis, MO

Photo: Associated Press

Today’s solemn occasion was first observed 137 years ago, when an Illinois Union general sent an order to Civil War veterans. John A. Logan wrote:

“The 30th day of May, 1868, is designated for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village and hamlet churchyard in the land. In this observance no form of ceremony is prescribed, but posts and comrades will in their own way arrange such fitting services and testimonials of respect as circumstances may permit.”

In many places throughout the U.S., Memorial Day will be publicly observed with the laying of wreaths; aboard the U.S.S. San Diego; at Hollywood Cemetery, near Richmond, Virginia, “honoring 76 former John Marshall High School cadets killed in the service of their country”; at the Intrepid Museum in New York. In Newport, Oregon, a fleet of boats will take memorial wreaths out into Depoe Bay, a custom six decades old.

And of course at Arlington National Cemetery, President George Bush laid a wreath this morning at the Tomb of the Unknowns.

Why all the circular arrangements? This story about the history of Memorial Day notes: “The fact that the (Civil) war ended during the flowering of springtime had much to do with the form the holiday eventually took. Some historians, including the one-time Chicago newspaper editor Lloyd Lewis, have also seen the day’s roots in the North’s elaborate grieving after the April 14, 1865, assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.”

In other words, this holiday for remembrance of the war dead was born in a flowering season, and in a floral era, when public expression took form in roses and sweet peas rather than opinion polls and souvenir t-shirts. That explains how flowers became part of Memorial Day, but why have they—floral wreaths in particular—endured, an observance even in our decidedly non-floral times?

Pres. George Bush

Pres. George Bush

Arlington National Cemetery

May 30, 2005

Photo: Mannie Garcia, for Reuters

According to Nora T. Hunter’s essay in The Centennial History of the American Florist, the wreath symbolized eternal life, eternal love, and “victory over death.” Before flat sprays came into fashion, in the latter part of the 19th century, “the wreath was the most requested sympathy design.”

I see wreaths used today, in the U.S. anyway, as emblems of collective sentiment, something different from personal emotion. As sympathy arrangements, they usually come not from the bank president but from the bank, not from John Wilkes Booth, but the Booth Family.

Likewise, when Bush lays the wreath at Arlington, he does so not as George Bush grieving a fallen soldier, but as the President of the United States honoring all of the nation’s war dead. Perhaps wreaths used to convey faith in everlasting life. Now, it seems to me, they symbolize community itself, whether of the living “posts and comrades” who present them or “the Unknowns” who receive them.

Wreaths acknowledge what Karl Marx called our “species being.”

Vascular Visionaries Do Georgia

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Saturday, May 22, 2010

Vascular Visionaries Do Georgia

Allen Bush “commences” once more with his gang of indefatigable plantsmen, scouring north Georgia in the funky month of May.

Georg Uebelhart goes vertical, plant hunting

Georg Uebelhart goes vertical, plant hunting

Yunnan, China, 1999

Photo: Dan Hinkley

By Allen Bush

I love graduations that feel like a tent revival: a mixture of triumph and prophecy. I see the light, no more darkness, no more night – and no more college tuition. Hallelujah!

My stepson just graduated with a mathematics degree from Reed College in Portland, Oregon. He’s an algorithm guy. I’m really proud of him. There were close to 400 graduates and each had to do a senior thesis. These papers aren’t cobbled together with consecutive all-nighters; they take more than a year to finish – no cakewalk.

The titles of some fascinated me. Take this anthropology thesis: “Constructing Das Deutsche Wessen through the Native American Other. German Indian Hobbyist Identity Development through the Experience of the Noble Savage and the Pursuit of the Imagined Authentic in American Indian Culture.” I should ask my Jelitto folks, in the German home office, to look at this. Or the history thesis “The Highland Bagpipe: Tradition and Transformation in Scotland, 1600 – 1850.” Reminds me of the joke: What is the definition of the perfect gentleman? Someone who knows how to play the bagpipes and doesn’t. The physics thesis was way over my head: “Accretion Disk Geodesics in Extreme Kerr Geometrics.” One history major’s thesis intrigued me: “The Secret’s Friend: Solitude and Masturbation in American Medical Discourse, 1800 – 1850.” But that was before my time.

And then there was the sociology thesis: “‘But I, Somehow, Someway/Keep Coming Up With Funky-Ass Shit Like Every Single Day!’: Artists’ Collaboration Networks and Success in the Case of Popular Music, 1992 – 2007.” Now, we’re talking! Not the music part, but coming-up with Funky-Ass Shit Like Every Single Day. I get that. It’s the gardening life— one enriched by friendships and collaboration with funky-ass folks who’ve never had a dull day in their lives. I am never disappointed visiting friends’ gardens or making a detour with them for the woods.

The Vitex Queen

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Friday, May 26, 2006

The Vitex Queen

Gardener and herbalist Ellen Zimmermann shares the glories of the “chaste tree.”

Vitex agnus-castus (with Turk’s cap)

Photo: Human Flower Project

Does the chaste tree enhance or suppress libido?

Now coming into bloom here in Austin, Vitex agnus-castus is also known as “chaste tree” and “monk’s pepper.” We’ve heard it was once planted around monasteries and “touted as an herb capable of helping Monks maintain their vows of chastity.” But if that’s true, wouldn’t it be called “monk’s balm” not “monk’s pepper”?

Herbalist Ellen Zimmermann discreetly recommends, “You be the judge.”

Ellen is known around these parts as “The Vitex Queen.” Through classes, demonstrations, her beautiful garden and her own glowing good health, she’s been spreading the news about this plant’s benefits for “women of all ages.” She names the chaste tree among her Top Ten Herbs: “The medicinal berries are used to treat PMS and menopausal symptoms, such as hot flashes and excessive bleeding. As a hormonal balancer, Vitex regulates progesterone and estrogen, treats fibroids and re-establishes normal ovulation and menstruation.” Hear me roar!

Ellen Zimmermann teaches in her garden southwest of Austin, TX, July 2004

Ellen Zimmermann teaches in her garden southwest of Austin, TX, July 2004

Photo: Human Flower Project

Ellen makes a simple tincture of vitex berries, usually harvested in July; they’re also a key ingredient in her “Menopause Made Easy” tincture. Find out lots more on Ellen’s website. Our favorite corner there is the monthly herbal newsletter, one of the very first dedicated, of course, to vitex. Ellen affirms that it “helps the body retain its natural balance after using the birth control pill. Vitex can also treat fibroids, inflammation of the womb lining and will enhance the flow of mother’s milk.”

If you’d like a second opinion, how about Hippocrates? He set down in the 4th Century B.C., “If blood flows from the womb, let the woman drink dark red wine in which the leaves of the chaste tree have been steeped. A draft of chaste leaves in wine also serves to expel a chorion (afterbirth) held fast in the womb.”

Interiors aside, we most appreciate lilac chaste tree for its beauty and hardiness here in the scorching South. Ellen suggests, “plant a small tree, in the sun, nurture it at first and then just about let it be. Vitex loves our summer heat and will thrive for years.” Bill Hopkins, a North Texas gardener and terrific blogger at prairie point, likewise paid tribute to vitex.

Its effects on libido? When Bill writes, “I can’�t imagine living without (a chaste tree) now,” and Ellen calls vitex “my husband’s favorite herb,” we get the picture, a mighty pretty one.

The Awakening

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Saturday, March 15, 2008

The Awakening

Cattle ranchers, church-goers, writers—those who look for signs will see them, especially in early spring. A yearning for fresh collards leads Jill Nokes to revelations in the fields of Granger and on the street in Houston. Thank you, Jill!

Testimony from the yard of Erma Lee, Houston, TX

Photo (detail): Jill Nokes

By Jill Nokes

At the end of February, I came across a recipe for minestrone soup that called for collard greens to be used in place of kale. Collard or turnip greens are typically not part of my cooking repertoire, as my mother was from New England and we never had that kind of food. But as I pondered over the selection of the large, coarse, bundled collard leaves in the grocery store, I held in my mind the many memories of driving past “truck” gardens in the country in late winter. I recalled endless versions of the same dirt plots, bare of everything except a few new onion sets and these tattered clumps of greens, waiting for spring. Old tin cans and wire cages would be hanging on the fence posts, ready for the tomatoes and purple-hull peas.

Spring in Texas is all about pure potential. Our short winters have usually brought us enough cold blasts to make people eager for the warm, soft nights of late March and April, and for a while we enjoy being in denial about the inevitable brutal heat and drought that waits on the other side of Easter.

Texas redbud (Cercis canadensis var. texensis)

March 15, 2008, Austin, TX

Photo: Human Flower Project

I always want to slow down the last days of winter and the earliest signs of spring. I don’t want my redbud to fade in eight days, and I don’t want the temperature to jump up to 85 degrees so soon after being in the comfortable upper 60’s. But signs of “The Awakening” appear more vividly with each day, even in between the last cold fronts.

I first heard the term “the awakening” from my friend Betsy Ross, who, with her son J.R. Builta, operate a grass-fed organic beef operation in the blackland prairies near Granger, Texas. After years of struggling to support their farm using conventional herbicide and fertilizer treatments for their land and feedlot finishing for their cattle, they discovered that only if they focussed on restoring the depleted soil biology in their pastures could their herds and planted forage crops thrive. To acquire the knowledge of just what their different pastures were missing, Betsy had to learn to be a keen observer of the signals Mother Nature was sending. And one of the most important things to watch for were the mystical signs that spring was on its way.

“What I heard from the Oregon Tilth folks a couple of years ago was that the earth begins to awaken slowly and, then one day everything pops up at once,” Betsy explained to me. “It is that ‘awakening’ that appealed to me, as for several years I could pick up a slow rise of upward energy out in the pastures. One can almost feel it beginning throughout 2-3 week period. When one is grazing intensively as we do, ‘catching this wave’ means we can begin grazing aggressively – because we know old winter is about over with and wonderful spring is about to explode and every green plant jumps up out of the ground. We can feed out the last of the hay with confidence, and let the cattle graze the grass a little shorter.”

Betsy’s description revives all kinds of notions of the romantic pastoralists: farmers who get intoxicated by the smell of warm, moist, living earth, the sounds of animals lowing in the evening, and the satisfaction of collaborating with Mother Nature to make things grow. The best thing about it is that they are actually succeeding in this holistic method of farming, and inspiring others to join them.

The Gathering Area, behind Erma Lee’s house in the Heights, Houston

Photo: Jill Nokes

Inspiration and awakening were also on my mind when I recently met Ms. Erma Lee, resident of Houston, in her amazing garden. On the way to meet a friend of my daughter’s soon-to-be new mother-in-law, we stopped off in the Heights neighborhood to meet Erma.

Erma’s “Inspirational Art Garden” is completely preposterous. Facing a busy street, the whole thing is made up of glass jars and vases, balls and vessels of all kinds, filled with colored water. Her special front bed is actually enclosed in store-front glass. It is ridiculously generous and fragile. Everything could be destroyed instantly by someone chunking a brick into the yard from a passing car. To Erma, this is not a concern, because God directed her efforts after she had “an awakening.”

Lee explains the biblical messages in “The Inspirational Art Garden”

Photo: Jill Nokes

As a member of Joel Osteen’s huge Lakewood Church (the 16,000 seat “worship facility” is located in the former Houston Rockets sports area), Erma was taught to make herself ready at any moment for a personal epiphany. So when it came about three years ago, she went into a whirlwind of activity, changing everything inside and out of her house, and began incorporating messages from biblical scripture into decorative arrangements on view for all to see. In the rear “gathering area,” she has constructed colorful backdrops using a signature style of figures made from old patio furniture and decorative fans from the Dollar Store. When giving tours of her place, she explains the meaning behind her decorations with the fervent zeal of a performance artist, and as someone who has been “awakened” to a higher purpose. For us lucky visitors, whether we are there because we are attracted to all the shiny glass like magpies, or because we yearn to be changed by a holy touch, we all benefit from Erma’s ardent creation.

Ecology • Gardening & Landscape • Religious Rituals • Permalink

The Botanist Gene

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Wednesday, June 30, 2010

The Botanist Gene

Is there a plant scientist among the limbs of your family tree? What kinds of fruit do botanists bear?

Tweedy’s Willow (Salix tweedyi): Thanks, Uncle Frank!

Image: State of Washington

Is there a gene for botanical talent? John Bartram seems to have passed it on to son William. There were the famous Hookers, father William and son Joseph, who both directed the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. And the Millers: Philip of the Chelsea Physic Garden and his son Charles, who became first Curator of the Cambridge Botanic Garden (1762).

On the eve the Tweedy family reunion out in Knickerbocker, Texas, this weekend, we are elated to have found a botanist-ancestor to call our own: Frank Tweedy (1854-1937). He worked for the U.S. Geological Survey in the late 19th century, exploring and collecting mainly around Yellowstone National Park, and several species from Washington State and the Rockies bear proof.

Cisanthe tweedyi (formerly known as Lewisia tweedyi) is all anyone could want for bragging rights. This beauty, native to Washington’s Cascades, is “valued by many experts as the world’s premier rock garden plant.” (Sounds like something alpine gardeners could debate long into the night.) Marc Dilley writes:

“It was named after Frank Tweedy, a U.S. Geological Survey botanical collector who made the first ascent of Mt. Stuart on August 5, 1883. Much of L. tweedyi’s renown is due to its extravagant bloom.”

Semana Santa

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Friday, March 25, 2005

Semana Santa

Alfombras (or floral carpets) glorify the sacred procession on Good Friday in Antigua, Guatemala

Alfombra

Alfombra

Photo: Semana Santa in Guatemala

With dirge music of brass bands and streets filled with the faithful and the merely amazed, Good Friday is the high-low point of Holy Week in Antigua, Guatemala.

For days in advance, various social and neighborhood groups construct alfombras—carpets made of sawdust, fruits, and flowers—both in the churches and along the streets. Some include Christian symbols—a cross, or an ox for St. Luke—others owe their designs to the woven patterns of huipiles, the garments of Guatemala’s indigenous people, still others incorporate more contemporary, popular messages.

But as human flower projects, the most spectacular are the alfombras along Antigua’s streets, meticulously designed and, ideally, completed just before the Good Friday procession begins. “Sand or sawdust is generally used to level the cobblestone roadway. Sawdust is then collected and dyed in different colors. Favorite colors are purple, green, blue, red, yellow and black. Flowers such as bougainvillea, chrysanthemums, carnations, roses and other native plants and pine needles are also used.”

There are several other interesting sites with explanations and images of the alfombras. But here is the most marvelous introduction I’ve found (in Spanish) to Semana Santa—Holy Week—throughout Guatemala. For the non-Spanish speaking, it’s still well worth visiting, with beautiful photography of processions all across the country, as well as the music of Good Friday marches, played by Guatemalan bands.

Good Friday Procession

Good Friday Procession

Antigua, Guatemala

Photo: Semana Santa in Guatemala

As for the alfombras, no one knows whether this custom came with the Spanish from Western Iberia (where floral carpets are made for Corpus Christi processions) or if the pre-Hispanic cultures of Guatemala were already making such ephemeral artworks from local flora. (We welcome your observations or research into this subject, por cierto.)

In any case, this tradition reaches to core of flower culture, likewise the human condition. Like Tibetan mandalas, but on a magnificent citywide scale, the alfombras are made to be destroyed. Here the message goes beyond our transitory nature. The alfombras pour out the spirit of sacrifice, in the re-enactment of Christ’s walk to Calvary.

Rose Of Jericho For Openers

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Saturday, December 30, 2006

Rose of Jericho—For Openers

The Resurrection Plant breathes life into the dead of winter.

Before: Odontospermum pygmaeum after years in a brown bag

Photos: Julie Ardery

Several winters ago at the turn of the year, we visited the shrine of Don Pedrito, famed folk healer of the Texas-Mexican border, down near Falfurrias. At the tiny gift shop next to the curandero’s shrine, we spotted what looked like a ball of dry, dead moss. What’s this?

“Rose of Jericho,” we were told, a plant that comes back to life, bringing good health and fortune. Sold to the gringa from Austin.

We brought this weird knot of vegetation home in a paper bag, and it sat on a shelf up high, untouched, until last week. This Christmas we would be traveling and couldn’t stand the thought of getting a tree and decorating it only to abandon it for the holidays. Then we spotted the old brown bag, took it down, and pulled out the Rose of Jericho. Maybe it could provide a miracle of Christmas greenery.

After: Two days in warm water—Ta-da!

After: Two days in warm water—Ta-da!

Submerged in a bowl of lukewarm water, over the next few hours and days it “bloomed.” The dry fist opened wide, turning a dark olive. Amazing. We changed the bowl-water each day to keep our “rose” fresh, and on the morning we left town splashed some of the healing water all four wheels of the car we’d be driving 2500 miles. We left the splayed out Rose of Jericho on a couple of paper towels to dry out as we’d been told to do, and returned—safely and happily—a week later, finding it brown and balled up again.

The name Rose of Jericho is used for several plants with these same magical behaviors: “Anastatica hierochuntica of the family Cruciferae (mustard)” and Odontospermum pygmaeum, “a member of the family Asteraceae (aster).” Ours appears to be Odontospermum pygmaeum or Selaginella lepidophylla.

An article from Garden and Forest (1892) says Resurrection Plants were brought to Europe from Asia Minor in the Middle Ages. “Many specimens were brought home by the Crusaders, and so highly were they prized, for semi-religious reasons, that they were often represented in the paintings on old shields which still exist in France.” (We quite like the idea of “semi-religious” and would describe the Human Flower Project as such.)

A semi-philosophical account of Rose of Jericho is of interest, too:

“For long periods, these ‘roses’ live in desert regions, growing and reproducing as any other plant until the environment no longer supports an adequate existence. When this time comes, they lose moisture, retract their roots from the soil and allow the desert winds to carry them across the desert, until one day they arrive in a place where they can continue to grow and spread. You could say they feel their way through this process, as they don’t necessarily remain in the first place they stop, but feel into the nature of the place to see if it is adequate to enhance growth. There they may stay, and grow, or indeed they may move again many times. But at all times, they feel, and trust to the movement that surrounds them.” Balled up, rolling, or in the flow.

A sales site from the UK considers the plant Mexican, claiming that Rose of Jericho has been “known since antiquity by its Nahuatl name Texochitl yamanqui and also as Flor de piedra or Doradilla. In Yucatan it is called Muchkok.” And this source refers to Selaginella lepidophylla as the Resurrection Plant, with a tale of the baby Jesus and Mother Mary. (Here’s a botanical look at it.)

Clearly, there are a number of wild things with this capacity for rebirth, a quality that has inspired knights and looters, voodoo priests and botanists alike. German-speakers seem especially keen on Anastatica hierochuntica. If our stills don’t thrill, check out this wonderfully choppy video of the Rose Anastacia opening.

After-after: Redried and ready for the next miracle-assignment

We weren’t the first to make Resurrection Plant part of a Christmas celebration and/but we intend to perpetuate the custom after this year’s “semi-religious” trial. A writer from Holland contends the plant “is said never to die, and thus being kept in families for over generations.”

To all of you, may the New Year bring generations of faith, experimentation, wonder.