Human Flower Project

Dole Won’t Bring You Flowers Anymore

The produce giant has sold its flower division, until now the biggest importer of flowers to North America.

Dole Fresh Flowers, offices and distribution center

Miami, Florida

Photo: Tilt-Up

Dole, which has been the largest importer of flowers to North America and the largest producer of cut flowers in Latin America, has sold its flower interests.

AP reports that the combined sales of Dole Fresh Flowers, some of its banana plantations, and additional real estate in North America will net $130 million “to pay down debt or to reinvest in the business.” As yet we’ve found no more information about why Dole chose to sell its immense international flower interests, how much the company gained from its flower division alone, or who its buyer(s) are. As always, we welcome those in the know to post comments (sources that prefer anonymity can contact us via .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)).

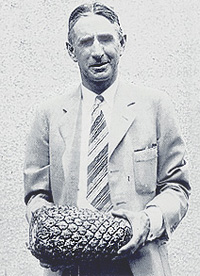

James Drummond Dole, founder

James Drummond Dole, founder

Photo: Harvard Library, via business history

The corporate king of perishables was born in the 19th century, growing and canning Hawaiian pineapples. Over the next hundred years the company diversified into other fruits and vegetables (and must have created several millionaires in the labeling and adhesive businesses along the way).

In 1998, Dole bought up several big players in the cut flower industry: Sunburst Farms, Inc., “the largest U.S. importer and marketer of fresh cut flower[s]”; rose importer and seller Finesse Farms; Four Farmers, Inc., an assembler and marketer of bouquets; and CCI Farms, an import business based in Miami. Dole anticipated that its flower division “would generate revenues of more than $200 million a year in the United States,” and initially the business decision seemed to pay off. “The floral industry’s growth” during these years “was attributed in large part to the increased availability of fresh-cut flowers in supermarkets, an arena in which Dole already held a commanding position.”

By December 2001, Dole had opened an immense cut-flower distribution center in Miami and was operating farms in Colombia and Ecuador that grew over 800 cut-flower varieties. A company report (undated) boasts that Dole produced more than 250 million stems of roses a year. The parent company’s net revenues in 2007 (including flower proceeds) were $6.93 billion.

Dole Fresh Flower greenhouse somewhere in Latin America

Photo: Dole Fresh Flowers

So why sell a goose that’s such a golden-egg machine? Over the past decade, Dole Fresh Flowers’ ongoing disputes with workers made for very poor public relations. (Isn’t just calling farm operations “plantations” a confession?)

Workers at two of the Colombian farms organized unions—Sintrasplendor and Untrafragancia – in 2004-05. But Dole refused to negotiate with the unions until public furor forced the company to do so, in late 2005.

At that same time Dole Fresh Flowers began “restructuring”: “The fresh flower business is highly fragmented and competitive,” reasoned company president John Amaya. “Industry oversupply has driven prices down, creating significant pressure on growers to improve performance. Latin American growers are also facing new competition from emerging markets in Africa and Asia.”

All this was wind-up to his announcement of “difficult decisions”: Dole would close all its Ecuadorian farms and two in Colombia – including Splendor-Corzo (where workers had first formed a state-sanctioned union). Dole would layoff 1275 more workers at its other “downsized” flower farms, as well as 35% of its “global sales force” and 29 percent of its management staff.

Dole flower processing operation

Dole flower processing operation

Photo: Dole Fresh Flowers

By the spring of 2006, the International Labor Rights forum reported that Dole Fresh Flowers had “reversed itself” on earlier agreements with workers – “and is backing a different process that does not provide protections for workers from possible reprisals for supporting the independent union. Dole has used a variety of ploys to deny Sintrasplendor its right to a collective bargaining agreement. It has also blocked the efforts of Untraflores-affiliated workers at its Fragrancia plantation to negotiate a contract.”

Adding to the confusion – OUR confusion anyway – a year ago, just in time for Valentine’s Day, Dole Fresh Flowers received certification from Florverde, one of a number of independent boards intended to vouch for cut flower producers, assuring that they “grow their flowers in compliance with environmental, social, labor and occupational health and safety standards.”

Sorry, we’re baffled. How does a company that closes down operations when workers unionize or penalizes workers who attempt to unionize qualifty? Had Dole Fresh Flowers come to an agreement with its union workers by this time?

We’re not sure but we don’t think so. And herein lies yet more evidence that trying to achieve justice for workers via industry-led certifications doesn’t make sense.

According to The International Labor Rights Forum, Florverde does evaluate firms on many counts, important ones like the regulation of pesticides in the work place. “Since 2003, 25% of Colombian flower farms have received a Florverde certificate, with a further 17% on track to do so. That means complying with 165 criteria, including commitments to seal off areas recently sprayed by pesticides and to impose a maximum working week of 48 hours with no more than 12 hours overtime,” according to the International Labor Rights Forum. Yet ILF has strongly criticized Florverde; Eva Seidelman of ILF writes, “Florverde’s certification process is weak. It ignores input from local worker advocacy groups and unions and thus, strong enforcement of standards is nearly impossible.”

This is a big hitch. Likewise,  “Cactus, an advocacy organisation, recognises some environmental improvements, but maintains that workers’ key right to association is still not respected on certified farms.”

“Cactus, an advocacy organisation, recognises some environmental improvements, but maintains that workers’ key right to association is still not respected on certified farms.”

We aren’t sure whether or how these labor conditions applied in the case of Dole Fresh Flowers, but we still ask – If certification of flower farms permits blacklisting of workers who try to unionize, what good is it?

Workers’ rights within the cut-flower trade still appear to be unenforceable. And for Dole, that’s now an un-problem.

Comments

I work for the International Labor Rights Forum, quoted several times in the article. The article makes it seem like we have positive views of the “Florverde” label: “According to The International Labor Rights Forum, Florverde DOES evaluate firms on many counts, important ones like the regulation of pesticides in the work place.”

ILRF HAS MANY CRITICISMS of the Florverde label. Despite the stats cited, the Florverde’s certification process is weak. It ignores input from local worker advocacy groups and unions and thus, strong enforcement of standards is nearly impossible.

The ILRF has been pushing ASOCOLFLORES, the owner of Florverde, to improve its weak standards for years and the industry association has taken few steps to adopt most flower worker advocacy groups’ recommendations. The certification and label initiative Fair Flowers Fair Plants, based out of Holland has a model process, far better than most of the other “ethical” flower labels.

Please read our blog post. “How sustainable is Florverde?” on this and correct your article, if possible. http://laborrightsblog.typepad.com/international_labor_right/2009/02/question-the-sustainability-of-the-florverde-flower-label.html

I heard that Dole has abandoned some if its fruit fields in the Sacramento Delta – it is cheaper to import fruit from China. Some of these former orchards now support vineyards.