Human Flower Project

‘Give Me Land, Lots of Land…’

Flower farming, a venture with promise in Africa, is stagnating in many nations as “land reform” runs aground. And there are other high hurdles ahead.

Zimbabwe lands

Source: FAS/USDA

As recently as twenty years ago, Africa’s flowers were minor leaguers in the global flower market. That’s not so today, as Kenya (principally) but now also Ethiopia and more southerly African countries plow ahead. They hope to best South America and China by likewise capitalizing on sunshine, cheap labor and open land.

But whose land is it? Confusion and, in some nations, violence over that question have made flower farming enormously risky business. Brigitte Weidlich’s story of a cut flower operation in Namibia is fresh, and representative. She writes of the Wiese family’s 90 year old farm, Ongombo West near Windhoek, which once “exported arum lilies to the Netherlands worth several millions of Namibia dollars annually.”

In 2004, it was the first farm to be expropriated by the Namibian government, after a labor dispute. The white owners had to relinquish their rights to the property. In the years since, according to Weidlich’s report, the farm has been idle; “all infrastructure, including the large green houses for the defunct flower export business, has deteriorated.” Six “erstwhile farmers” who were resettled there to work the land have had to hire out on neighboring farms. And now the national Ministry of Lands has posted a want ad, hoping to attract “experienced and reputed engineering companies for the assessment of rehabilitation required for existing irrigation infrastructure.”

A Namibian official calls the situation at Ongombo West “a delicate issue”—another way of saying “big flat flop.”

In Zimbabwe, resettlement has been crueler. Land reform began with the election of Robert Mugabe in 1980. Britain, the former colonial power here, pledged 630 million GBP to implement a “willing seller, willing buyer” approach to land redistribution. Problems began right away and intensified with each passing decade. White farmers were not “willing” to sell; then, the Mugabe government gained first right to purchase available lands, but could not afford to do so. Agricultural production, further hampered by drought and rising fuel costs, stagnated.

In 2000 Zimbabwe voted on a new constitution that would have permitted Mugabe’s government to take lands away from white owners without compensation: i.e. expropriation. The referendum was defeated. But after the elections, pro-Mugabe forces decided to carry out their version of “land reform” anyway. They began forced “liberation,” taking about 42,000 square miles of white-owned lands.

“It is clear that the land resettlement program has been an economic disaster, with dramatic drops in agricultural productivity and economic growth,” writes Markus Scheuermaier.

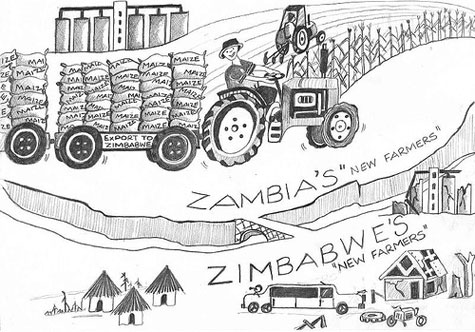

Cartoon pointing up Zimbabwe’s corrupt “cell phone” agriculture, dominated by elites, while Zambia’s farmers, many of them displaced from Zimbabwe, thrive.

Image: Sokwanele

African rights cannot overreach human rights, he contends. But this is just the most obvious flaw in Mugabe’s version of land-reform. Scheuermaier looks as issues of practicality as well as justice. Once an exporter of food, Zimbabwe has not been able to feed its own people since 2002. “In March 2004, an estimated 7.5 million people (or about 60 percent of the population) were dependent on food aid provided by the international community,” he reports. “Agricultural production has collapsed, and where land has been allocated to peasants the government has failed to provide inputs to allow them to sustain production on their new plots. Owing to poor rains, many have since abandoned their plots, and commercial farmers have not returned, fearing intimidation and violence.”

Meanwhile, South Africans have been monitoring Zimbabwe’s gruesome example closely as they, too, work toward land reform.

“At the onset of democracy in 1994, some 87 percent of (South Africa’s) agricultural land in the country was owned by whites, who make up less than 10 percent of the population. Thirteen years later, around four percent of land, or four million hectares (nearly 10 million acres), have been transferred to blacks.” The South African government has “promised to redistribute 30 percent of white-owned land by 2014.”

How will that happen, safely and fairly?

A bill that would have allowed the South African government to expropriate property from whites and turn those lands over to black South African farmers failed last week. White farmers are, of course, jubilant. Now, how will the promise be kept?

Economists, agronomists and policy-makers at the Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies are at work thinking options through, at least in the abstract. But hunger, land and, for that matter, flowers are not abstract, and making the leap from public policy to political reality is daunting, as Zimbabwe’s example proves.

About 150 years ago, Karl Marx was working on the same problem, also in the abstract:

“Centralization of the means of production and socialization of labor at last reach a point where they become incompatible with their capitalist integument. Thus integument is burst asunder. The knell of capitalist private property sounds. The expropriators are expropriated.”

All right. But then what happens? Considering the flower industry, a small but growing sector of southern Africa’s agricultural economy, both Marx and well-meaning 21st century scholars (Communist or not) typically fail to consider two crucial features of commerce.

First, it always takes intellectual capital to turn “means” like sunny land into productive use. In Zimbabwe, notably, the first lands “expropriated” were handed over to urban bureaucrats. What would they know about blackspot on roses?

There is evidence that traditional farmers, small shareholders, have managed some success on these newly acquired lands, despite all the forces against them in Zimbabwe. “This could be because they farm in more labour intensive ways and are less dependent on purchased inputs and fuel which have been in short supply because of wider economic problems,” writes Ben Cousins, director of the Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies. Cousins says these small land-holders have done especially well with cattle herds.

Cattle farmers, near Paul Roux in the Free State, South Africa

Photo: Aquila

They’ve been less successful in highly capitalised sectors of farming, or, Cousins says, “where long-nurtured market relationships have been undermined, such as in the tobacco or horticulture sector.”

In other words, it’s not just land, inputs and training that are lacking in southern Africa—but social capital. The flower market, more than most others, has historically functioned as a fairly tight-knit business, dominated as we all know by the Dutch. One of the most powerful investigations of this strange and beautiful commodity’s inner workings is Alex Strating’s study: “Kinship, Family and the Flower Trade in a Dutch Community.”

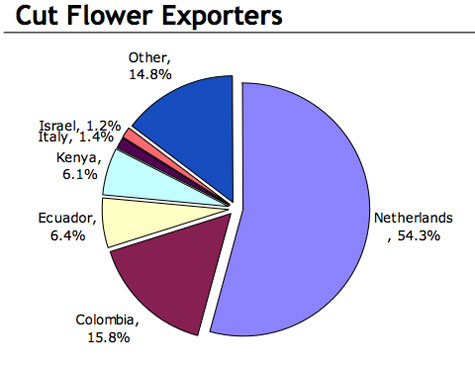

Global flower exporters by value ($5.7 billion market), 2005

Source: International Trade Center

Though Strating concentrated on the town of Rijnsburg, in the Netherlands itself, his study of closely-held firms there offers revelations about the flower industry as a whole. Through generational chains, family members (most of them male) pass along secrets of the trade. They also train novices in the multi-tasks involved—buying/packaging/transportation/sales—and can safeguard the names of their customers. Furthermore, Strating found that the tight ties of these lijnrijders made it possible to withstand the inevitable seasonal vagaries of this business – the crush of holidays followed by lean months, and, always, calamities of weather. Family members tended to be more willing to take pay cuts during hard times or stay after hours when orders flooded in, working along with the peculiar rhythms of the flower business.

This is not to say that such knowledge and social circuitry don’t exist in Namibia or South Africa or Zimbabwe. For in some respect, they must. But these are “means of production and socialization” that don’t come quickly or easily. And they sure don’t just happen with a windfall of property, whether that’s called “liberation,” “expropriation” or “land reform.”

An excellent essay. The inclusion of Marx is genius. Not to bring US politics to HFP, but the recent mocking of community organizing is nonsensical. One of the goals of organizing is to develop social capital. Social networks work as you brilliantly highlight with the example of the lijnrijders.