Human Flower Project

Ecology

Tuesday, April 03, 2012

The Pollination Racket

A new study of birds finds that human noise is tough on pines but a boon to skyrocket flowers.

Will earplugs be the next trendy gardening accessory, this year’s Crocs?

New research by Clinton D. Francis and his colleagues suggest that in some environments anyway, noise may actually improve flower pollination. It’s a finding that will much dismay those of us who think of puttering outside as a respite from racket.

Francis and his team examined the effects of noise on plant pollination by setting up experimental stations at two spots within the Rattlesnake Canyon Wildlife Area in northwestern New Mexico. One location was relatively quiet, but the other was adjacent to a natural gas well operation, with big machinery and compressors at work around the clock.

Wednesday, February 15, 2012

Weaving among Hardiness Zones

Kentuckian Allen Bush pushes the limit with new plants from Florida, seduced by the USDA’s new maps.

Edgeworth chrysantha: an early bloomer, “insanely intoxicating”

Photo: W.J. Hayden

By Allen Bush

The long awaited interactive garden tool was released a few weeks before our Florida vacation. I didn’t study the new map, though I could see Louisville, Kentucky, was colored some shade of green. There were adjacent greens but I’m red-green colorblind. It was all a muddle.

On our vacation to Sanibel Island, a few weeks later, Mary Vaananen, my Jelitto colleague, emailed and announced that Louisville had been upgraded from 6b (-5 F to 0 F/-20.6 C to -17.8 C) to 7a (0 F to 5 F/-17.8C to -15 C). I started shopping for native Florida plants the next day. Florida and Kentucky have a lot in common. Florida once sat at the bottom of an ocean floor; so did Kentucky. In 1824, botanist Constantine Rafinesque wrote in Annals of Kentucky: “The briny oceans cover the whole land of Kentucky.” Kentucky was only 10 degrees north of the equator, when we were sitting under a shallow ocean in the Devonian Period 380 million years ago.

Saturday, January 14, 2012

Ash Assassin

Taking out one endangered tree seems to cause more alarm than the threat to a whole species. Allen Bush takes out an ash and takes on the neighborhood.

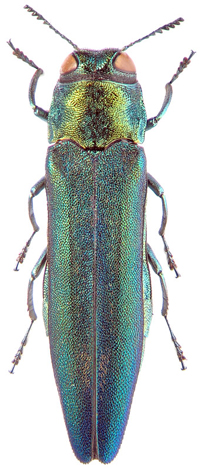

The Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis B)

The Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis B)

Photo: Zin

By Allen Bush

Arborists cut down our big white ash tree a few weeks before Christmas. It had stood in the front yard since 1974. My neighbors weren’t happy with me. My pleas for any understanding fell on deaf ears throughout the holidays in coffee shops, at parties, on the street. I promised everyone that there would be a better tree that goes in its place.

“Good luck,” I was told.

“We’re tree huggers!” one critic added. No one seemed to know what kind of tree it was, or even care why I’d taken it out. None of that mattered. Our tree was their tree. “What a bummer,” one passerby lamented.

At least the neighbors weren’t marching down Top Hill Road in solidarity, carrying Louisville Slugger baseball bats made from white ash wood, at least not yet. “I see you took the down the tree,” is not a neutral declaration. It means I have looted the neighborhood. I am the ash assassin.

Nobody cared that the tree removal was a preemptive strike, ahead of the emerald ash borer (EAB). This insect has already launched an assault on tens of thousands of ash trees in Louisville alone.

Our white ash (Fraxinus americana) should never have been planted in the first place, at least not in our front yard. (White ash grows naturally from Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, south to northern Florida. It extends west to eastern Texas and eastern Minnesota.)

Thursday, December 15, 2011

The Unforeseen: Yahoo Falls

Plantsmen Allen Bush and Paul Cappiello, hunting for pink muhly grass, fall down a rabbit hole of botanical wonders in McCreary County, Kentucky.

Silene rotundifolia blooming near Yahoo Falls

McCreary County, Kentucky, November 2011

Photo: Allen Bush

By Allen Bush

I had no idea what was in store last spring, when Paul Cappiello began talking about an autumn day-trip to Eastern Kentucky. Paul is the Executive Director of Yew Dell Gardens in Crestwood, Kentucky. The premise – or the excuse for a fun walk in the woods – seemed simple enough: try to find cold-hardy native stands of the pink muhly grass, Muhlenbergia capillaris. They were there, somewhere in the Cumberland Mountains; we knew that. Julian Campbell had said so. And Julian knows where just about every native plant is, in every nook and cranny across the state. He had found pink muhly seedlings in Rowan County earlier in the year.