Human Flower Project

Search Results for:Kew

Geobotany Rocking The Garden World

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Tuesday, April 22, 2008

Geobotany: Rocking the Garden World

Nature first put flowers on stone pedestals, but gardeners of the Picturesque school followed, with painterly landscapes of their own. Well done, say the EarthScholars: But, please, give rocks equal time!

Trees, Fort Greene Park, 2004

by Kerry O’Neill

By James H. Wandersee and Renee M. Clary

EarthScholars™ Research Group

Unwittingly, people view landscapes through the lenses of their prior knowledge and experiences. They compare the new landscapes they visit with ones they already know. Given that more than half of the world’s inhabitants now live in big cities, more and more people lack an extensive personal knowledge of nature. Nor have most people, urban or otherwise, traveled to explore a variety of conserved natural ecosystems —experiences they could use in making comparisons and aesthetic decisions about the new landscapes they encounter.

There are many theories about how humans perceive landscapes. The Australian environmental scholar Andrew Lothian poses the question: Is landscape quality inherent in the landscape or in the eye of the beholder? He opts to defend the latter.

R.P. Taylor, writing in the journal Leonardo, recalls that, “In art school I was told that Monet’s water lilies calm the observer, while van Gogh’s sunflowers electrify. To what extent, however, do paintings [of landscapes] really affect the observer’s physical condition? The foundations of this question date back to 1890, when the connection between psychological states and physiological states was first considered.”

A famous African Savannah,

A famous African Savannah,

the Maasai Mara

Photo: Masai Mara

Judith Heerwagen, in her article on the Psychosocial Value of Space, notes: “Drawing on habitat selection theory, ecologist Gordon Orians argues that humans are psychologically adapted to and prefer landscape features that characterized the African savannah, the presumed site of human evolution….If the ‘savannah hypothesis’ is true, we would expect to find that humans intrinsically like and find pleasurable environments that contain key features of the savannah that were most likely to have aided our ancestors’ survival and well-being.”

Features of the savannah landscape include a fairly unobstructed “big sky” view, a high diversity of flowering plants, scattered clusters of trees with high canopies, swaths of open grassland, occasional rocky outcrops, multiple visual corridors, and topographic changes to enhance predator surveillance and long-distance escape movements.

Do humans really prefer these, or other, particular landscapes? History shows us that colonialists and emigrants sometimes attempted to transform their new landscapes of residence into replicas of those they had known. Presuming the superiority of “The Old Country,” they tried to mimic what they considered “civilized spaces”—importing plants, seeds, and even rocks from their landscapes of origin.

Just as people’s first maps showed their tribes or cities at the center of the world, it is common for us all to judge new landscapes by the rather xenophobic criteria of familiarity and congruence with our original cultural values and preferences.

In 18th century England, complex debates developed about the essence of beauty in the landscape—with followers of the ‘Sublime’ school inspired by wild, natural landscapes (simultaneously fascinating and startling), while those of the ‘Picturesque’ school wanted ‘painterly’ landscape views (human-designed to be blurred, disjointed, and soft composites of color and contour).

Followers of the latter were willing to have flowering plants moved from their traditional positions in borders or against walls, provided they were regrouped to form non-linear, painterly compositions (“painting with plants”). The eye of the landscape artist (painter), with its aesthetic understanding of nature and training in the principles of composition, was thought to be the best guide to good planting design.

Plant Hunter Joseph Dalton Hooker’s Rhododendrons of the Sikkim-Himalaya (1849-51)

Plant Hunter Joseph Dalton Hooker’s Rhododendrons of the Sikkim-Himalaya (1849-51)

Image: Garden Visit

The Picturesque school had a pronounced effect on landscape design. It both justified using foreign plants in British gardens and provided a system of compositional principles to harmonize the intermingling of exotic and native plants and natural objects. Instead of the plantings being natural of themselves, landscape designers were to use art to imitate rugged natural scenes in aesthetic ways.

In the second half of the nineteenth century the Picturesque Style was used, for example, in the making of woodland gardens. Landowners on the western shores of the British Isles installed rhododendron woods, arranged in “painterly compositions.” As can be seen from Hooker’s print (above), the art that inspired Paxton’s landscape (below), making effective use of jagged irregular lines of plant and rocks, represents the furthest possible conceptual distance from an artificial geometrical regularity. In contrast, fractal geometric patterns predominate—for both plants and rocks.

Landscape at England’s Birkenhead Park, Designed by Joseph Paxton

Photo: Garden Visit

Like Charles Darwin, Joseph Dalton Hooker saw the need to integrate botany and geology to understand nature. When he was only 5 years old, Joseph regularly attended his father’s botanical lectures at the University of Glasgow, and displayed a genuine interest in the subject. Because his parents thought Glasgow High School’s curriculum was too limited, he and his brother were withdrawn from formal schooling to be home-schooled. In those days, botany was still regarded as merely a branch of medicine, so like every other young Glaswegian botanist in his day, Hooker studied for his medical degree at the University of Glasgow. This education later proved to be quite expedient because, in 1839, Sir James Clark Ross, famous discoverer of the magnetic north pole as well as his father’s good friend, offered young Joseph the position of Assistant Surgeon on Clark’s expedition to the Antarctic, aboard the discovery ships Erebus and Terror.

This four-and-half-year voyage allowed Hooker to botanize in many lands and also to notice the natural relationships between botany and geology. At the Kerguelen Islands, where Captain Cook had managed to collect just 20 new species of plants, Joseph identified and collected over 150 different species, including flowering plants, 3 ferns, 35 mosses, and the rest lichens and seaweeds. This was no easy task, as the cold, harsh weather and rough terrain made collecting very challenging. Hooker wrote: “Many of my best little lichens were gathered by hammering out the tufts, or sitting on them till they thawed.” Joseph later became assistant director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, near London.

One result of the English affinity for Picturesque landscape design was an enthusiasm for rock gardens. A European rock garden, also known as an alpine garden, features extensive use of rocks or stones, along with plants native to rocky alpine or tundra environments.

Alpine flowers on tundra along Trail Ridge road

Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

Photo: Q.T. Luong

In 1803, Europe’s first alpine garden was constructed at Belvedere Castle in Vienna. The best rock gardens were designed and built to look like natural outcrops of bedrock (e.g., limestone, sandstone). Stones were aligned to suggest a bedding plane and plants were often used to conceal the joints between the stones. This type of garden was especially popular in Victorian England as well.

The first rock garden of appreciable size to be constructed at an American botanic garden opened at Brooklyn Botanic Garden in 1917. Today, some of the best alpine rock gardens may be viewed at the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh, Scotland; Le Jardin Botanique Alpin du Lautaret, Grenoble, France; Cambridge University Botanic Garden, Cambridge, England; Royal Horticultural Society Garden, Wisley, England; New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY; Devonian Botanic Garden, Devon, Alberta, Canada; Göteborg Botanical Garden, Gothenburg, Sweden; Betty Ford Alpine Gardens, Vail, Colorado; Jardin Botanique de Montrèal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; and the Tromso Arctic-Alpine Botanic Garden, Tromso, Norway.

A Picturesque rock garden at Chatsworth Manor, England

Photo: Michelle Anstett

Although the use of rocks as decorative and symbolic elements in gardens can be traced back to very early Chinese and Japanese gardens, rock gardens dedicated to growing alpine plants have a shorter history. During the age of the great plant explorers (basically, the 1800s) there was great interest in the exotic discoveries being brought back to England, and people wanted to grow these amazing new treasures successfully. Although others had previously written about growing alpine plants, it was actually Reginald Farrer who, with the 1919 publication of his two-volume book The English Rock Garden, rocked the gardening world for the first time. There was great interest in Farrer’s method and approach to creating large-scale, naturalistic settings for growing alpine plants.

(For more about the man credited with starting the rock gardening craze, read Nicola Shulman’s biography of Farrer).

Alpine Crevice Garden

Alpine Crevice Garden

Alpine Garden Society Center

Pershore, Worcestershire, England

Photo: Stone Garden

Because our own research group focuses on the integration of botanical and geological knowledge, we strongly recommend that public rock gardens interpret both the plants and the rocks that are present. The public trails we have designed always include geobotanical interpretation. As visitors tread the rock garden’s paths examining the alpine plants, we think it is helpful for the visitors to understand the geologic history of any garden site, to know what kind of rocks they are seeing and their influences on plant growth.

We appreciate, for example, University of Florence’s Botanical Garden exhibit that interprets the geobotany of the alpine plants of Italy’s Dolomite region via a simulated outcrop of limestone derived from the Dolomite Mountains themselves. Similarly, we think the rock garden at the Botanic Garden of Montreal is exemplary from a geobotanical perspective. It’s not only a rock garden, but also a mineralogical garden, with rocks and minerals drawn from all over Canada.

Finally, if you live in the US, be sure to experience the Denver Botanic Garden’s remote 1.5-mile Walter Pesman Trail through the alpine tundra on Mount Goliath, a mountain peak section of the Mount Evans area within the Arapaho National Forest (17 miles from Idaho Springs). Volunteer guides will interpret not only the plants but also the rocks that you see in this “nature-made” alpine rock garden, but only during the summertime days when the alpine flowers are in bloom, June 26th to August 7th. (Reservations are required: phone 720-865-3539). The Denver Botanic Garden within the city also has a fine rock garden, with thousands of different rockery plants collected by Panayoti Kelaidis—the godfather of American rock gardening.

We conclude with a passage from author Donna E. Schaper: “Building a quiet [sanctuary] of stones and plants, slowly and meditatively over time, is [a rock garden’s] true meaning. Process over product, journey over destination, forever a work in progress—rock is the best metaphor we have of everlastingness.”

Art & Media • Culture & Society • Gardening & Landscape • Travel • Permalink

Get Around Garden Panoramas

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Sunday, July 22, 2007

Get Around: Garden Panoramas

This garden project by an international band of geo-photographers will knock your socks off and turn your head all the way around.

19th Century Garden, Dolenjska, Slovenia

Boštjan Burger

Via: World Wide Panorama

A garden is a 360-degree experience, hard to capture in a still photograph. Close-ups are too short and buggy, wide angles too distant and angelic. And we miss what’s going on above, below, behind the camera.

Rubbernecks and inquiring eyes will be twistfully delighted by Gardens, a collection of interactive panoramas all taken between June 20-25, 2006. Here from Damascus, Syria, Gloucester, Massachusetts, to Himi City, Japan, are scores of gardens—garden visits, really—since, as we move the virtual “eye” across the screen, we are turning around in each environment. You can look down a path in Bodoe, Norway or over a field of pink wildflowers to the Spanish Coast at Coruna, or behind you at a group of hikers in flowerless Queens Garden, Utah.

Photographer and geographer G. Donald Bain at the University of California Berkeley founded the World Wide Panorama project with Landis Bennett. Here on the web, 360-degree photographers from around the world come together four times a year (at the equinoxes and solstices) to document a different theme. In advance of last year’s summer solstice, Don sent out a probing invitation to Gardens. He’s graciously permitted us to excerpt his letter:

A Garden of Delight, Kammeny Privoz, Czech Republic

Jeffrey Martin, Prague

Via: World Wide Panorama

“Nobody need travel very far to find an interesting subject, or interpret the theme as a metaphor. Just look around, think about what makes gardens in your particular place special and distinctive, then find a good example with photographic possibilities.

“Gardens range from prim little front yards, just lawn and flowerbeds, to elaborate landscapes with plants originating from all over the world, or for that matter fruits and vegetables. Some gardens are small and private, others open to the public and world famous.

“One way of looking at gardens is that they embody our ideals for a vegetated space – filtered by cultural context and physical environment. What makes a garden in Arizona different from one in Connecticut, Hawaii, Italy, Mexico, Alaska, Japan, or Brazil? Each will have distinctive aspects that set it apart from the others….

“Given our ability to alter the environment, even more important than physical factors are our expectations and desires. What do we want from a garden – organic vegetables, brilliant flowers, species native to the region, unusual plants from all over, shade from the sun, shelter from the wind, impressive vistas or intimate spaces? How do we want to manage it – manicured, casual, or wild?

“Each culture evolves its own aesthetic of landscaping. Some are widely understood and emulated – everyone recognizes a classic Japanese garden, for example. But most gardens are subtle variations on a cultural/environmental theme, modulated by local circumstances and individual preferences, and sometimes by institutional mandates.

19th Century Garden, Dolenjska, Slovenia

Boštjan Burger

Via: World Wide Panorama

“Every major city has one or more famous gardens, often city parks. London has the Chelsea Physic Garden, established in 1673 to collect and study medicinal plants. San Francisco has the Japanese Tea Garden, a by-product of the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition. Kyoto is famous for its temples, including the unique raked gravel Zen gardens. The Missouri Botanical Garden in Saint Louis is a world leader in botanical research as well as a public park. Banyan Park in Lahaina on the Hawaiian island of Maui is covered by a single huge banyan tree.

“Vegetable and fruit gardens reflect culture and environment. In what environments would you expect the following to be grown: olives, apples, papayas, avocadoes? Tomatoes, rhubarb, vegetable marrow, okra, tomatilloes?

“Botanical gardens serve two purposes, research and public education. Some display the vegetation of the world, others focus on the local area. They are usually laid out geographically and all the plants should be labeled. Some contain unusual or unique plants, such as the Victoria lily at Kew Gardens near London, or Captain Bligh’s breadfruit on the West Indian island of Saint Vincent….

“So, take a good look around you, try to interpret the physical and cultural reasons for what you see planted, where and why. Choose a garden, large or small, private or public, flowers or vegetables or lawns. Find a way to bring out its special beauty and interest in your panoramic photography. Learn all about it and write a good caption. Easy!

.(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

Don Bain

Geographer at Berkeley”

Livia’s Garden, near Front Royal, Virginia, USA

Rose Hughes Steuart’s reproduction of a Roman fresco

at Poplar Forest, a recreation of Thomas Jefferson’s home

Skip Steuart

Via: World Wide Panorama

Scan through thumbnails of all the panoramas or look for gardens by region and nation. This is surely the most amazing human flower project we’ve encountered in months. We especially enjoy how some photographers have dwelled on the human—for example, Rodolpho Pajuaba in his Garden of Ronaldos from Brazil—while others focused on flora or fauna, (feline, in this case). Many of the gardens are grand and famous, others humble.

A Garden of Delight, Kammeny Privoz, Czech Republic

Jeffrey Martin, Prague

Via: World Wide Panorama

We hope that readers will get around this thrilling site and let us know your favorites. And we thank Don Bain and these three marvelous photographers for permitting us to share their work here. One final note and question, while looking at these panoramas, we have had the distinct sense of visiting each garden WITH someone. Is it this 360-degree format that turns photography—normally a private and contemplative experience—into something that feels sociable?

Garden Going Since Before Gardens For

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Thursday, September 13, 2007

Garden Going Since Before ‘Gardens For’

Revisiting nurseries and public gardens, John Levett catches sight of Henry James but still hasn’t found “The Pottering Garden.” If you have a map to it, .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address) in Cambridge, England.

At Cambridge Botanical Gardens

At Cambridge Botanical Gardens

Photo: John Levett

By .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

Since when did the thought of going to a garden bring about palpitations of anticipation? Not recently? Not since the last time? Err…about 1984? Well, sometime around then. Or maybe it was just the last time when the arrival matched the picture in the head. Maybe I’ve had enough of gardens. Not gardening (although I start to flag this time of year). Just other people’s.

I was walking with a friend around Docwra’s Manor just outside Cambridge last year and realised it was the walkin’ and the talkin’ that made it and the thought of ‘this is the sort of place you get cream teas with scones and clotted cream and homemade blackcurrant jam and sticky fingers and nuclear strength tea imported in wooden casks from the Empire’ (it wasn’t).

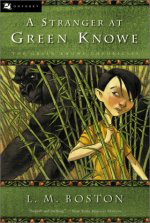

Similar thing the year before. A friend was house-sitting for the Summer somewhere on the river near Hemingford Grey and would I fancy coming over for the evening and I did and it was The Manor where Lucy Boston had written the Green Knowe books. It was late evening and chilling up and friend’s dog went missing and so did I on the search and walking through the garden silence gave grounds for belief in the underworld.

Similar thing the year before. A friend was house-sitting for the Summer somewhere on the river near Hemingford Grey and would I fancy coming over for the evening and I did and it was The Manor where Lucy Boston had written the Green Knowe books. It was late evening and chilling up and friend’s dog went missing and so did I on the search and walking through the garden silence gave grounds for belief in the underworld.

So back to 1984, which had the best of times. And Ingwersen’s Nursery down in Sussex. For reasons now lost I’d got a passion for alpines. Read the books, bought the troughs, got the greenhouse (Yes! I know it’s not the same as an alpine house but it could pass for one!), seed from the Caucasus and points east sown but I wanted Instant Alpine and Ingwersen’s looked like it had the pedigree.

It was early April, bright, frosty, dawn. I drove down the A1, cleared London passing a ‘Troops Out’ protest in Parliament Square (Ireland in those days) and ate breakfast of salmon sandwiches at Biggin Hill overlooking the Weald listening to Johnny Mathis singing ‘Stardust.’ It’s still that clear. Ingwersen’s wasn’t a let down. They had the troughs and the alpine houses and the stone outcrops and the miniscule flowers which looked just like the illustrations and a steam railway at the bottom of the garden. It only needed three children in buttoned-up costume and their mother gathering her skirt and an old gentlemanly gentleman and ‘They were not the railway children to begin with.’ The thing I can’t recall is how much I spent. Guilt and memory consorting.

From that moment that nursery came to be a special place. Mustn’t go there too often then. So I didn’t but when I did it was always the first Saturday in April and the start time and the route and the salmon sandwiches on Biggin Hill stayed the same. Going back to special places needs its routines and its history. Then going back’s past its time. My last visit reminded me of what I knew—place has to do with time and how we were then and who and what was in our life.

Kew Gardens is like that for me, too. My mum, gran and me were always going to go to Kew for a day out but we never did. Gran died, then mum, by which time Kew had taken on myth. I got there in 1988 when life was spiritless and a friend called and said ‘Here’s a day out.’ We had lunch at The Old Rangoon near Hammersmith and thence to Kew but for my life then it was Hardy’s heath or Bronte’s moor at their most bleak. I arrived back there last year to see the new alpine house. Closed for repair, so I walked through the trees and sat by the Thames at Syon Reach, out of the crowd’s way, read and slept.

Cambridge Botanical Gardens

Cambridge Botanical Gardens

Photo: John Levett

I had similar feelings last week. I had a morning when I wake up and think ‘I’m closer to death than I was ten years ago so why am I spending time doing this’ and then restructure my morning accordingly but fall off the plan at half-past-one and take the (metaphorical) dog for a walk. To Cambridge Botanical Gardens. I’ve lived near botanical gardens (or ones that look like them) throughout my life and can see the Nineteenth Century point of them and they make sense in the current epoch when seen as places of work but I’ve never got much fun out of them. Which meant that I turned up there with a strop on. (Going places annoyed at the thought of being there is a part of me I should deal with.)

History first. Darwin learnt there and C.C. Hurst speculated there on the origin of the rose. Enough.

I got taken with incidentals—the age of one to whom a seat was dedicated (forty-four’s no age to die); the noise of grass cutting, tree felling and traffic on Trumpington Road; a cat stalking ducks; a group of day-trippers tripping from bed to bed; yet another alpine house under renovation. And gardening as an industry.

It wasn’t so many decades ago that I used to stop off at the Rose Society’s gardens in St. Albans on my way home from a day’s teaching, shattered and in need of head-space; hardly a soul around; seats and beds and acres of island. Standing-room only now. Last Thursday it touched me that I’d become a Larkin-like mitherer—the crowds and the prams; the intrusions of working days into one’s own day; the concessions to the current public taste. Maybe it was the acknowledgement of the current zeitgeist that we have to be gardening ‘for’ something—the Dry Garden (no watering required), the Fen Garden (repopulate the wetlands), the Winter Garden (no time off for good behaviour elsewhere in the year), the Fragrant Garden (now with wind chimes).

The Pottering Garden? I couldn’t see it. The one where you walk about clipping a bit, thumb-in a cutting, layer a trailer, scrape a space for some bulbs, shift this to there. I passed the ‘listers’, secretary-like with pen and pad, readying for the raid on garden-centre, website and Tesco. Clear the space, break the pot, heel in. Sorted ‘til the next generation. Like decorating a room.

Towards the end of the afternoon I walked out towards the far edges of the garden to where the staff were finishing off. There was a young lad there, maybe late teens, maybe an apprentice. I remembered leaving school in 1960 aged fifteen. There were three employment options open—metalwork, carpentry and gardening. It was still (just) the age of ‘a job for life’ and there were still lads who’d go into gardening, maybe in the municipal gardens, maybe on an estate, and stay there for the duration and into a pension. I wondered if this lad tidying up the beds of hardy geraniums, wiping off his tools, collecting the scattered pots would still be hoeing fifty years hence, not rushing but giving plants, and himself, time.

Cambridge Botanical Gardens

Cambridge Botanical Gardens

Photo: John Levett

I was going through one of my periodic ‘Modern Times’ moments—remembrances of gardens strolled through by Barbara Pym characters and maiden aunts with grans. Then, for reasons unknown, thought of Henry James. James furnishing Lamb House in Rye; choosing plants for his walled garden as he chose furniture for his rooms; matching foliage to brick as he would tapestry to panelling. Then I thought of him arranging his papers and his pens, his shelves, his working ways with his views, his chairs with his fireplace, his comfort with his protection.

Then I thought ‘just like me’. The garden as comforter. I reflected on how I arrange my chairs around my garden; the morning site, the mid-morning-coffee site, the lunch-time-snack site. How the time must be ‘just so’ to catch the sun above the warehouse wall (no problem for James with that one!); the annoyance of next door’s children out early on Sunday (very Henry); saving the un-read article to partner the cake-treat from Fitzbillies (how to explain that, should he be seen?) My garden for me is the pair of slippers, the useful cardigan, gloves that fit, Marty’s recliner, Norm’s bar stool. Sometimes ‘the garden for the bone idle’; other times ‘the GWF Hegel garden’; in my mind’s eye ‘the John Cassavetes garden’ (think scripted but improvised); never ‘the Princess Diana bring your lame and sick garden’ (ten years and still no miracles?).

I walked towards the exit in late sun and met a couple sitting near the water garden; a daughter and her father who was working in the gardens at the outbreak of war in 1939. I thought of a conversation with him but thought better; he looked tired, or lost elsewhere. I left with a pleasantry and went looking for tea. I snuck something out and sat in the part of my plot known as the woodland garden—nine square metres underneath next door’s tree, next to my ferns and R.Davidii with its autumn heps. There was probably noise. No mithering.

Art & Media • Culture & Society • Gardening & Landscape • Travel • Permalink

Flowers Eclipses

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Wednesday, March 29, 2006

Flowers & Eclipses

A solar eclipse brings hush, grey light and—for some flowers— a strange nap.

Partial solar eclipse, Amman, Jordan: March 29

Photo: Ali Jarekji, for Reuters

While others were straining to look through safety telescopes or special protective glasses, Ali Jarekji of Reuters sighted today’s eclipse on flower petals (via a pinhole, we suspect). The golden crescent of partial eclipse appeared on a flower in Amman, Jordan, and Jarekji had the brilliance to capture it with his camera.

The path of the eclipse began in Brazil, touching (among other lands) Ghana, Libya, the Greek Island of Kastellorizo, and Turkey, before “setting” in Mongolia at 11:48 GMT.

“It was more fabulous even than we expected,” said Jay Pasachoff, a U.S. astronomer, viewing his 42nd solar eclipse. “It’s one of those experiences that makes you feel like you’re part of the larger universe,” said Janet Luhman, a scientist with NASA.

A garden, under 60% solar eclipse, March 2003

A garden, under 60% solar eclipse, March 2003

Photo: Haneveercoreman

As a new moon passes between the sun and Earth, the light becomes green-gray. The picture at right shows an eerie garden during an eclipse March 10, 2003.

In some cultures, this sudden nightfall during the day was cause for serious self-appraisal. Here’s a bit of Ethnoastronomy from Lithuania.

Until recently, “the belief was still alive that during solar eclipse it’s best to stay at home, pray and beg God to forgive our sins and protect from disaster. When at home close window shutters and cover the windows. Sometimes (people) lit candles and burn(ed) the Sunday palm flowers. The cattle would be kept inside the sheds in fear that during the solar eclipse they may contract a disease or get blind if they stay outside. It is said that during solar eclipse the cattle would make wild sounds and bend on their knees.”

Birds and flowers are likewise subdued. Daytime bloomers—like gazania, poppies, tulips and portulaca—all close as the moon intervenes. Perhaps they “think” it’s night or —like early Lithuanians—they, too, feel chastened.

Wild Flower Eclipse

Photo: by John Foster

This site notes: “There may well be sudden bursts of wind around totality – resulting from the sudden change in temperature. Watch for unusual patterns and shadows on the ground and on buildings. Watch the behaviour of people around you!”

Good advice, eclipse or no.

(Many thanks to John Foster of Portland, OR, for permitting us to post his fine photo of what happens when a wildflower passes between the sun and Earth.)

Elites Wildflowers And Conservation

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

Elites, Wildflowers, Conservation

How does wildlife preservation come about? Two examples suggest it’s the exertion of human wealth and power, not the threat of natural or even cultural extinction.

Carpenteria californica blooming at the Mary Elizabeth Miller Preserve near Prather, California.

Photo: Irfan Khan, for LA Times

What does it take to save a flower, an acre, a mountain, a cultural region?

Diana Marcum’s fascinating story for the Los Angeles Times is a microcosm of conservation history, recounting the the survival of Carpenteria californica, a rare white wildflower of the Sierra foothills.

It was “discovered” by a 19th century explorer, John Fremont, who lost his way back to the original wild clump. Later a Swedish scientist came upon the plant, collected seed, and sent it to Kew Gardens, where Carpenteria californica was grown into showy specimens, a wonder for horticultural pros and visiting amateurs.

Carpenteria’s homeland in Fresno County was purchased by two “Utopian” sisters, who eventually amassed 1500 acres in the area. One of them took a special interest in the wildflower and came to consider it her private emblem of peaceful resistence during World War I.

The tale goes on…. Crucially, it involves other California elites—wealthy landowners, intellectuals and philanthropists. As we read Marcum’s account, it’s clear that through their resources of leisure time, money, organizational experience, and clout, they were able to create a nature preserve on the plant’s habitat. In league with the national Nature Conservancy, the Mary Elizabeth Miller Preserve was founded.

Detailed Enough To Insult Flower Sculptures By Shou Ping

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Sunday, May 18, 2008

Detailed Enough to Insult: Flower Sculptures by Shou Ping

With paper, paint, and scrutiny, a Taiwan-born artist tames the wildflowers of her adopted country.

Passionflower (Passiflora incarnata), by Shou Ping

Photo: Human Flower Project

When we think of paper flowers, usually we envision blooms like these, de rigueur for any good party in South Texas or Mexico. So how mind-expanding to encounter the works of Shou Ping recently at the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center.

Shou Ping’s paper sculptures combine the delicacy of a confectioner and the precision of a botanist. She shapes flower replicas, right down to the threadlike stamens, from paper, paints them in watercolors, and then frames them in glassed shadow boxes. (Note: her Wildflower Center show ends today.) Nothing could be less like the gay bobbing stems of crepe paper flowers you see at a Cinco de Mayo fiesta. Shou Ping’s pieces are ultra still, studious and quiet. For us, they possess an elegance reminiscent of porcelain flowers (topic for another day’s post, to be sure). We also found them slightly morbid; pressed flowers usually strike us this way, too.

Sunlight applauds a stunning piece by Shou Ping

at the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center

Photo: Human Flower Project

Trained in both art and commerce, Shou Ping has worked as a cartoonist and graphic designer. A native of Taiwan, she moved to the US in 1993 and now lives in San Antonio. Perhaps her paper works are inspired in part by cork sculpture, a popular craft in Asia, for it, too, often depicts plants and landscapes and likewise is displayed under glass. But she’s quite obviously been swept up with a fascination for native Texas plants. How carefully she’s looked at wine-cup (Callirhoe involucrata), white dog’s tooth violet (Erythronium albidum), and—our favorite of her depictions—dayflower (Commelina erecta), also known as “widow’s tears.”

Dayflower (Commelina erecta)

Dayflower (Commelina erecta)

detail from a paper sculpture by Shou Ping

Photo: Human Flower Project

We learned in Geyata Ajilvsgi’s excellent Texas wildflower guide that this flower, with its two larger bright blue petals and one tiny “teary” white one, conveys a put-down. “Swedish botanist Linnaeus named this plant for the three Commelin brothers, Dutch botanists, two of whom were very productive in their field. The third brother published nothing and was relatively unknown. Linnaeus used the flower’s three petals to represent the traits of the three brothers.” Shou Ping’s rendering is true, right down to the insult.

For more about this artist, her watercolors and paper sculptures, visit her website.

Widely Winged

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Widely Winged

After years of assiduous transnational work, botanists at Kew coax an iris into bloom for the first time.

Iris stocksii bloomed in cultivation for the first time 1/23/12, at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew.

Photo: Andy McRobb

We imagine Tony Hall swinging through the door of a hospital maternity ward: “It’s an Iris stocksii!”

Congratulations to Tony, to Kit Strange, Juan Piek and everyone else involved in finding the rare bulbs in Afghanistan and handling them with such wisdom and care that the first flowered last month at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. (And our thanks to Allen Bush for informing us all along the way.)

We are delighted and grateful to post in full Tony Hall’s fine description of this beautiful flower, its “gestation” and birth. A more complete scientific description may be found here.

If you’ve ever wondered how a top notch working horticulturist thinks (hyper-observant, meticulously historical), this account is revealing. (We’ve taken the liberty of dividing Hall’s four paragraphs into shorter passages for ease of reading online.)

Self-portrait of a juno iris expert, Tony Hall

Image: Courtesy of Tony Hall

Iris stocksii flowers at Kew

By Tony Hall

“I observed two flower buds forming on one plant of Iris stocksii in late December 2011. I had not expected such recently collected bulbs (2010) to flower so soon, especially as this species come from a semi-desert habitat with searing hot summers (in my experience, junos from such regions are notoriously difficult to maintain and flower, e.g. Iris postii & I. edomensis from the Middle East). However, our hero Juan Piek had very carefully cared for and packed his bulbs before despatch so that, although the fragile storage roots were detached (which invariably weakens bulbs), the bulbs arrived at Kew in remarkably good condition.

An image of one of the bulbs of I. stocksii, taken by Kit Strange in September 2011, during repotting, shows how well its rootstock, with newly formed slightly fleshy roots, had recovered during its first year in cultivation. Kit is our Bulb Horticulturist in the Alpine Unit at Kew, who repots and cares for the juno collection from day to day, with some guidance and advice from me. The 1st flower opened fully at Kew on the 21st January 2012, and was taken to Kew’s photographic studio for Andy McRobb to photograph three days later.

Bulb of Iris stocksii, a year after arriving at Kew, showing newly formed fleshy roots, September 2011

Bulb of Iris stocksii, a year after arriving at Kew, showing newly formed fleshy roots, September 2011

Photo: Kit Strange

“Iris stocksii is well represented in herbaria although it has never been successfully cultivated before, as far as I can ascertain. Furse’s material of the closely related I. odontostyla was grown for a time and even flowered, in the late 1960s/early 1970s, at both R.H.S. Gardens, Wisley, and in the private collection of the late Dr. Jack Elliott, a very skilled grower of bulbous plants. Alas, few of those Paul Furse juno iris treasures from Afghanistan, collected in the 1960s, nor the slightly later collections of Kit Grey-Wilson & Tom Hewer, are still around and that includes I. odontostyla.

“Iris odontostyla is represented by a single type specimen in Kew’s Herbarium, although that is accompanied by wonderful notes and line drawings executed by Furse in the wild; unfortunately, the capsule and seed characters of I. odontostyla are unknown, but this taxon is likely to have non-arillate seeds like I. stocksii.

“Iris odontostyla appears to be restricted to Herat Province in W. Afghanistan, whilst I. stocksii, although found in this Province, has a much wider distribution in W., E. & S.E. Afghanistan; it also occurs in adjacent Pakistan (N. Baluchistan).

“It is worth comparing the colour image of I. odontostyla in the British Iris Society’s 1968 Year Book with Juan Piek’s plant of I. stocksii…they are remarkably similar in overall habit and flower colour, although the former is said to have slightly more greyish tints to its flowers and its outer tepals (or falls) a slightly different outline, and not so widely winged as in I. stocksii.

“Another distinguishing feature of I. odontostyla (as its specific epithet suggests) is irregularly toothed or scalloped style lobes, but Andy McRobb’s images show clearly that this feature can be observed in I. stocksii as well.

Close-up: the flower parts of Iris stocksii, January 26, 2012

Photo: Andy McRobb

“The chromosome count and karyotype of Iris stocksii were unknown, but have now been studied at Kew’s Jodrell Laboratory by Jaume Pellicer; I. stocksii has a count of 2n=20.

“We were also able to sacrifice a few of Juan’s original seeds for DNA extraction, in time to be added to our molecular study of the junos (Ikinci, N. et al. 2011. Molecular phylogenetics of the juno irises, Iris subgenus Scorpiris (Iridaceae), based on six plastid markers. Bot. Journ. Linn., 167 (3), 281-300). This study shows that I. stocksii falls into a small clade of rather distantly related species, primarily from the Hindu-Kush, which includes Iris cycloglossa and I. aitchisonii. Probably I. microglossa also belongs here but is unresolved in the analysis, as well as I. odontostyla, which was not available to sample.”

Comments

Commenting is not available in this channel entry.Urmas Laansoo Lets Do The Moss Crawl

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Urmas Laansoo: Let’s Moss Crawl

Allen Bush introduces us to an Estonian plantsman who specializes in lichens and pillowcases. Thank you, Allen.

Hallan Kivisaar’s sculpture garden, Estonia

Photo: Allen Bush

By Allen Bush

I traveled to Austria and Italy with The Ratzeputz Gang in September 1991 to visit nurseries and gardens. My favorite memory is a leisurely luncheon on nurseryman Lorenzo Crescini’s hillside near Brescia (Italian plant hunting requires eight-course nourishment and Barbaresco wine). Before heading back to North Carolina, where I had my own nursery at the time, I left my horticultural running mates and flew to England, making a beeline to Cambridgeshire. It was dark by the time I arrived at Joe Sharman’s home – too dark to look around for new perennials at Sharman’s Monksilver Nursery, a few miles down the road.

It was dinnertime. Sharman’s’ business partner, Alan Leslie, was there. He works full-time as a botanist at the Royal Horticultural Society garden at Wisley in Surrey and comes-up on weekends to tend to nursery chores. Joe’s mother prepared a nice meal for a table of gardeners and guests. It felt like a tiny arena. Hundreds of books were stacked high like bleachers around the edges of the dimly lighted room. There was plenty of jostling Latin binomial nomenclature at ringside.

Urmas Laansoo, lichen and pillowcase expert

Urmas Laansoo, lichen and pillowcase expert

Monksilver Nursery, Cottenham, Cambridge England 1991

Photo: Allen Bush

At the opposite end of the table was an unidentified man. I guessed he could be Sharman’s brother. No one introduced him; no one spoke to him – perhaps for familial good reason. I wasn’t sure. He didn’t say a word. Finally, late in the dinner, Alan Leslie presented the quiet one—a visitor from the Tallinn Botanic Garden. I’d never met anyone from Estonia. Urmas Laansoo surprised me and said he’d never met anyone from the United States. For better or worse, I had presumed that everyone had met an American.

(Ten years later, in 2001, a few days following September 11, I was in Pong Bu, a little western Sichuan village. Before then it had seldom occurred to me what the privilege and responsibility of being an American could mean. My plant collecting party surprised a school full of young Tibetan kids who crowded around, staring at odd people they had never seen before. I worried hairy Caucasian arms would be my legacy. These sweet children followed us part way up the mountainside – bright-eyed and curious – unaware of what was going on in the next village, much less the other side of the world.)

The Russians kept a stranglehold on Estonia for nearly fifty years, but the empire collapsed in August 1991 and Estonia declared its independence. Estonians were free to travel. Urmas had high-tailed it to England. He wanted a glimpse of what was going on in the gardening world. The Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew overwhelmed him. It was “like heaven, just fabulous … we had empty shops at home and food-shortages…you were allowed to buy sugar and milk, soap and matches in a very limited way…I felt too full of plants, visiting Kew Gardens, just too much of new plants for the first time visit!”

Urmas and I chatted a bit that evening and picked-up the conversation the next day while wandering around Monksilver’s fascinating collection of rare perennials. We’ve kept in touch since. I look forward to his holiday greetings.

At this time of year, his countryside is dark and usually snow covered. Mine is gray and sodden. It’s a good time for Urmas to get away, and the Indian Ocean has its appeal. Here and only here is his favorite tree: Mathurina penduliflora, endemic to the Mascarene archipelago. Urmas explains, “There are only 30 individuals left. It’s critically endangered in the wild. It grows only on Rodrigues Island in Indian Ocean. We have named this tree in Estonian language as “Tree of Cheerful Tears”! As I met the tree the first time on Mauritius Garden of Pamplemousses (Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam Botanical Garden), I started to cry, it was so beautiful and unique! And still is!”

Staff of the Tallinn Botanic Garden – (from left) Mari Seidelberg, Krista Kaur, Urmas Laansoo, Taimi Puusepp – in the garden of plant Estonian collector, Sulev Savisaar. In front is the rare Chinese Jack-in-the Pulpit, Arisaema ciliatum var. liubanense

Photo: Siiri Liiv

Urmas started work at the Tallinn Botanic Gardens as a schoolboy in 1978 but traces his gardening roots to February 1966, in the village of Kohila. He was the tender age of four. With the nudge of his grandfather, he started cucumber seeds, on a windowsill. He still lives – and gardens – at the same childhood home. Today Urmas is a botanist on the education staff at the Tallinn Botanic Gardens, author of books, and television presenter of nature programs, leading excursions in Estonian, Russian, Finnish, and English. There’s no hint that he is ever bored.

In late May 2003 I made a two-day visit to see Urmas with Ratzeputzers Klaus Jelitto and Steve Still. After a few days in St. Petersburg, Russia, we arrived in Tallinn after a day-long bus ride driving past small towns and birch forests carpeted with ferns. (Air travel between the two cities wasn’t possible due to a lingering political feud between the two countries.) From occasional communications over the previous eight years, I supposed that Laansoo was probably a pretty competent plantsman, but I had no idea what to expect. Plantspeople can be peculiarly one-dimensional and sometimes as obsessive – and boring—as stamp collectors. Rare in this breed is the outlier who can keep a couple of balls in the air at once. Normalcy and obsession are at odds. Urmas is interested in history, music and literature and is thoroughly entertaining – and normal.

Hallan Kivisaar’s sculpture garden, Estonia: ideal for a moss crawl

Hallan Kivisaar’s sculpture garden, Estonia: ideal for a moss crawl

Photo: Allen Bush

We crawled around in these woods looking at mosses and lichens.Urmas showed us the impressive collections at the Botanic Garden. There were particularly large accessions of Peonies and Iris. And Phlox species and cultivars were on his radar screen for new acquisitions. But Urmas, though crazy about plants, skipped the chest-thumping so common among collectors. He’s as modest as he is brilliant. The rock garden included some alpine gems that he had been able to collect in the Pamirs of Tajikistan, near the Afghanistan border, and Tian Shans in Kazakhstan. The glass houses and Palm House are filled with tender species – some from collecting trips to Tenerife, Gran Canaria and La Gomera islands.

For bragging rights plantspeople will talk sometimes about how many rare things of this and that they’ve got tucked away. (Urmas doesn’t brag about plants but mentions he collects pillow cases and Christmas lights.) Some of the more interesting gardening characters have a working knowledge of the native species that grow in nearby woods and meadows. Precious few know much about mosses and lichens.

And endangered, I’m afraid, is the gifted natural educator, like Urmas, who can get you on your hands and knees crawling around in the woods looking at mosses and lichens as he spins a dazzling botanic yarn that makes your head revolve. You feel like an idiot when you get-up; you don’t know diddly. But your senses have been jolted, because you never imagined “this-is-fun” value in lower life forms.

Urmas also gave us a peek at a Baltic Bronze Age cemetery, and we visited a few very interesting local nurseries and gardens. I wouldn’t know a Benjamin Franklin Z Grill postage stamp if I saw one. But thanks to Urmas I know a little about mosses and lichens. Hang around long enough and I might get a bug for pillow cases and Christmas lights.

Comments

Vascular Visionaries Do Georgia

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Vascular Visionaries Do Georgia

Allen Bush “commences” once more with his gang of indefatigable plantsmen, scouring north Georgia in the funky month of May.

Georg Uebelhart goes vertical, plant hunting

Georg Uebelhart goes vertical, plant hunting

Yunnan, China, 1999

Photo: Dan Hinkley

By Allen Bush

I love graduations that feel like a tent revival: a mixture of triumph and prophecy. I see the light, no more darkness, no more night – and no more college tuition. Hallelujah!

My stepson just graduated with a mathematics degree from Reed College in Portland, Oregon. He’s an algorithm guy. I’m really proud of him. There were close to 400 graduates and each had to do a senior thesis. These papers aren’t cobbled together with consecutive all-nighters; they take more than a year to finish – no cakewalk.

The titles of some fascinated me. Take this anthropology thesis: “Constructing Das Deutsche Wessen through the Native American Other. German Indian Hobbyist Identity Development through the Experience of the Noble Savage and the Pursuit of the Imagined Authentic in American Indian Culture.” I should ask my Jelitto folks, in the German home office, to look at this. Or the history thesis “The Highland Bagpipe: Tradition and Transformation in Scotland, 1600 – 1850.” Reminds me of the joke: What is the definition of the perfect gentleman? Someone who knows how to play the bagpipes and doesn’t. The physics thesis was way over my head: “Accretion Disk Geodesics in Extreme Kerr Geometrics.” One history major’s thesis intrigued me: “The Secret’s Friend: Solitude and Masturbation in American Medical Discourse, 1800 – 1850.” But that was before my time.

And then there was the sociology thesis: “‘But I, Somehow, Someway/Keep Coming Up With Funky-Ass Shit Like Every Single Day!’: Artists’ Collaboration Networks and Success in the Case of Popular Music, 1992 – 2007.” Now, we’re talking! Not the music part, but coming-up with Funky-Ass Shit Like Every Single Day. I get that. It’s the gardening life— one enriched by friendships and collaboration with funky-ass folks who’ve never had a dull day in their lives. I am never disappointed visiting friends’ gardens or making a detour with them for the woods.

Uebelhart checks his horizonal: Tai Chi in Salzhausen, Germany 2010

Uebelhart checks his horizonal: Tai Chi in Salzhausen, Germany 2010

Photo: Iris Uebelhart

Georg Uebelhart, my colleague from Jelitto Perennial Seeds, flew to Atlanta from Germany in early May. The Swiss national, a brilliant plantsman, favors wild collected porcinis at home and prime rib (medium) on the road in the U.S.

Our days were filled with trilliums, coneflowers and Jack-in-the pulpits. They began with Tai Chi and ended with steaks. Our rule: there would be no beef in the evening unless we moved some chi in the morning. We practiced in Gainesville, Georgia’s Poultry Park (a far cry from the Shanghai Bund but just as wonderful). The small park featured a tall obelisk topped-off with a laying hen (or was it a fryer?).

Tai Chi has slow moves that the uninitiated might suspect as looking peculiarly psychotic-like, but there were no hecklers—even with Uebelhart in fine fashion—on any morning anywhere, from Gainesville to Dahlonega.

For five days we stayed in constant motion in the company of Georgia crackers with a perennials predilection. Our friends are vascular visionaries of xylem and phloem – top-notch collectors, breeders and gardeners. Plant talk was non-stop. What cracker is this…that deafes our ears…With this abundance of superfluous breath? Name a plant – perennial or otherwise—and chances are someone in this posse knows it, covets it, has had the joy of seeing it in the wild or the good fortune to grow it – sometimes very successfully. These folks follow a different drummer down unusual garden paths. All are passionate, tireless, wonderfully kind-hearted and a little odd. The world could use a few more like them.

Richard and Bobby Saul are leading breeders and garden innovators. They’re also a marquee tag team, the Coen Brothers of the plant world. The Sauls have their complementary strengths. Bobby has the horticulture degree and tends to business while Richard, who holds the business degree, looks after horticulture. World renown was sealed after their introductions of colorful Echinacea cultivars. Their Cone Crazy line includes ‘Harvest Moon,’ one of the longer-lived cultivars, and they also maintain two wholesale sales yards, catering to the busy Alpharetta and Atlanta wholesale landscape trade.

Their greenhouses are like Pee Wee Herman’s Playhouse of odd mutations that might end-up one day in gardens. It’s unlikely anyone can match their diverse offering, running the gamut from pansies, perennials, green roof succulents, tropicals, andd rare ferns to their own Mr. Natural line of soil amendments. But their strongest virtue might be the talent they identify and hire. Karen Stever, a Ph.D. chemist, works miracles in the tissue culture lab, and plant collector Ozzie Johnson discovers exciting new species, and interesting new plant forms, around the world.

Ozzie Johnson tends one of his Leyland Cypresses, Marietta, GA

Ozzie Johnson tends one of his Leyland Cypresses, Marietta, GA

Photo: Lisa Bartlett

Johnson has a superb one-acre garden, in Marietta, crammed to the gills. Don’t come a’knockin’ if you’re looking for colonial Williamsburg. This is not a boxwood by the front door sort of landscape. The iconic pair of mammoth Leyland cypresses is the takeaway here. Ozzie should consider a helicopter airlift for the annual pruning (he is 66) but still handles garden adventure with a 32’ ladder and pole pruners to reach the top. He’s used to the high wire. Near Wolong, Sichuan, in 2001, he recalled “The time I got lost and stuck on a ledge, lost my balance and grabbed tufts of green that saved me and it turned out to be Epimedium davidii. I vowed never to put myself in that situation ever again… Until I went to Vietnam.”

You’ll miss a lot on a garden walk-around in Johnson’s garden if you only do one circuit. Take another look. You might miss the epimedium that saved Ozzie from peril. Much of what’s here, Johnson has found in the wild in remote corners of China, Vietnam, or Japan where he has been over 35 times—collecting species in six prefectures and developing close relationships with Japanese nurserymen.

Woodwardia unigemmata, a Chinese woodland fern collected by Ozzie Johnson

Photo: Georg Uebelhart

Woodwardia unigemmata, a stunning woodland fern with broad arching fronds, was collected at an elevation of 4,500’ near Peng Jia Ba, Sichuan, China, in 2004. Schefflera megaphylla, a handsome, small shrub, hardier than many tropical species, was collected in the mountainous Lao Kai Region in Northern Vietnam. And many of Johnson’s asarums (over 40 species and cultivars) – lovely woodland wild gingers—have been wild collected in the southeastern U.S. and Asia or procured in Japanese nurseries.

Scott McMahan and Ozzie Johnson, funkiphiles and plantsmen, in the jungle

northern Vietnam near the Chinese border

Photo: Dan Hinkley

Scott McMahan owns McMahan’s Nursery, with his wife Kristie, in Clermont, down the road from the Saul’s Alpharetta operation. His Asia plant collections are trialed and propagated here with the help of Tiffany Jones. He is also a partner in Gardenhood, an innovative downtown Atlanta retail nursery that was bustling on a unusually cool Saturday. McMahan, in his mid-30s, is the bright, young star in a horticultural demographic overcome with aging dirt daubers. He gained an appreciation for the outdoors from his grandfather but cut his teeth in Sichuan in 2001, while in his twenties, then employed as Nursery Manager for the Atlanta Botanic Gardens. He has returned to China twice under his own auspices and also ventured to North Vietnam, Bhutan and India.

In Clermont, he is at home wandering the hoop houses pointing-out hardy impatiens, meadow rues and Solomon’s seals from far-flung outposts. An Aristolochia species, perhaps A. aff. kaempferi, collected near the Tau Yuan village in mountainous northern Sichuan in 2004, not far from the Gansu border, seems destined for more U.S gardens. The rare, semi-evergreen Clematis repens, with yellow bell-shaped blooms, and the narrow-leaved form of Impatiens omeiana – a perennial species with good heat tolerance—look promising, too.

-mcmahan475.jpg)

Impatiens omeiana, a narrow leaved variety, collected by Scott McMahan and being trialed at his Clermont, GA, nursery

Photo: Georg Uebelhart

Don Jacobs moves through the garden with a dancer’s grace, impressive for a garden legend who will be 91 this fall. He continues to sow seeds, divide nursery stock and mail order plants from the five-acre Eco Gardens he has tended since the early 1970s. (Jacobs has co-authored, with son Rob, the highly respected American Treasures: Trilliums in Woodland and Garden.) Trained as a botanist, with time served as a wholesale tropical fish supplier, he was, in 1983, riding one of first waves of western plant explorers in Sichuan, after Richard Nixon normalized China relations with Chairman Mao.

Jacobs’s nimble mind keeps track of an extraordinary assortment of plants, tucked in the ground around his ranch-style house, in sections he calls China Cove and the Japanese Corridor. He has also collected an impressive collection of native plants from the southeastern U.S. including lady’s slippers, trilliums and phlox species. His coral bell introduction, Heuchera americana ‘Eco-Magniflora’, found in western North Carolina, grows as well as any of the newer fancier cultivars. (Eco is the familiar name associated with many of Jacobs’s plant introductions.) His Asian garden influence parallels the evolutionary development and subsequent glacial separation of 120 genera that have disjoined populations in eastern Asia and temperate North America. Cypripedium, the lady’s slipper genus, is one good example; Jacobs has brought some back together after millions of years apart.

Bobby Saul, half of Georgia’s horticultural tag-team

Bobby Saul, half of Georgia’s horticultural tag-team

Photo: Georg Uebelhart

Richard Saul guided Uebelhart and me in the north Georgia mountains for a day—not fifty miles from where Eric Rudolph, the Olympic Park Bomber, evaded FBI capture for five years, holed-up in hillside caves. Rudolph was finally caught while dumpster diving in Murphy, NC. (Uebelhart is a mad man for plants, not a profile high on the list for U.S. Homeland Security and apparently no threat. “Are you going to the Kentucky Derby? “ U.S customs asked. “No, it was last weekend,” he answered. )

Saul drives while Uebelhart sits in the back with his x-ray eyes trained on the roadside. He can spot odd forms of wild gingers (Asarum species) 100 feet deep in the southern Appalachian forest while driving along windy mountain roads, where peanuts are being boiled in country stores around Suches and Turners Corner. Crested iris, mayapples, galax, golden Alexander and twinflower are on view. For the first time, we see Indian cucumber, Medeola virginiana, and the American columbo, Frasera caroliniensis – that’s some Funky-Ass Shit.

E.H. “Chinese” Wilson wrote about plant exploring on Sichuan’s sacred Mount Emei in Naturalist in China published in 1914. Resting briefly in a transitional zone of temperate and subtropical species between 4,500’ and 5,000’ in southwestern China, Wilson reminisced, “Everything around us looks so smiling that all nature seems to be at peace.” Uebelhart and the Georgia Funky-Ass Folks, all of them in love with gardens and nature, know the feeling.

Comments

As a Georgia, I was tickled to read about the very cool plantsmen in Georgia. Thanks, Allen. By the way, I’d never before seen a Leylandii in picture or in person. Ozzie Johnson’s is impressive.

Thanks, Georgia. These folks are wonderful and Ozzie’s Leylands are a sight to behold.

what an all-star trip…literally. thanks!

Thank you, Victor. Never a dull moment with this bunch!

To Paint Two Roses

By on February 28th, 2022 in

To Paint Two Roses

An artist in Cambridge, Massachusetts, sets out on a new subject. With Manet to help him over triviality-block, Nick Read finds flowers “obstinate” and glorious.

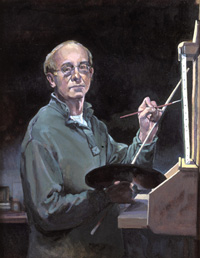

Self-portrait, by Nicholas Read

Self-portrait, by Nicholas Read

By Nicholas Read

When a friend asked me recently to describe what it was like to paint flowers, I had no ready response. I am a painter, but the subjects I choose do not include flora. Nothing against it, but the question caused me to wonder whether flower painting Is different from painting, say, the Maine shoreline, a pretty young woman, a dog, a horse, a ship, or any of thousands of possible subjects?

This is what I found out.

A trip to Google brought me immediately to “Painting Flowers.” The BBC teamed up with the National Gallery and public galleries across the UK to create this unique online art exhibition of flower paintings. They were joined by the Royal Horticultural Society—“ to explore the vivid theme of flower painting in art.”

The site includes interesting information. For example, flower painting is over 3500 years old: paintings of lilies dating from 1580 BCE were found in a villa in Crete. The figure of Flora in Botticelli’s famous painting in the Uffizi, Primavera, strews identifiable flowers over the garden on which she walks (as discussed, for example, in Levi d’Ancona, Botticelli’s “Primavera”: A Botanical Interpretation, Olschki, 1983).

The intensity of van Gogh’s sunflowers reflects innovation in the fabrication of artists’ pigments, notably the introduction of chrome yellow. (By the late 19th century, the vibrant yellow was one of a series of new and exceptionally vivid colors. Chrome yellow is actually a lead salt, lead chromate (PbCrO4). The pigment is still used today but it has been replaced in many cases by similarly colored, less toxic organic pigments. Unfortunately chrome yellow degrades over time; van Gogh’s once brilliantly glowing sunflowers, for example, now appear to be dry, drab ocher shadows.)

Branche de pivoines blanches et secateur (1864)

Edouard Manet

Photo: Musee d’Orsay

But what about actually painting a picture of flowers? How does one get started? Which flowers does one choose? Coral Guest, a contemporary British artist featured on the BBC website, describes it this way:

“You can simply pick the plant up, put it in front of you, and say “All right, that’ll do,” or you can look and turn and experiment and sketch and find within that flower an arrangement which has a kind of naturalistic appeal which says something about the real character, the real personality, real demeanor of that subject that you are looking at.

“When you do look at the plant in that way, you find that as you look between the leaves and stem and the angle of the flower, what you get is a particular, almost an arabesque shape. When that’s placed on a white page, you have to consider those shapes in between the parts of the plant because the whole thing holds together as one. And this happens almost intuitively when the artist finds the right place or the right way to display the plant on the page. It can be the difference between someone looking at something and being interested and looking at something and being amazed by it.”

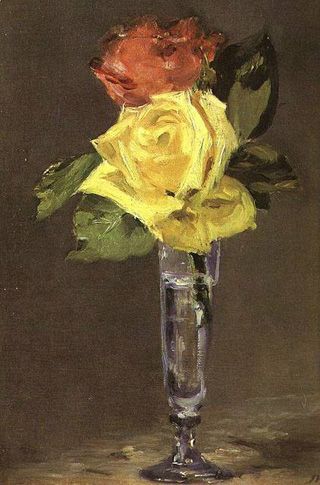

Des Roses dans un Verre à Champagne (1882)

Des Roses dans un Verre à Champagne (1882)

Edouard Manet

Photo: SCVRS

I looked at many pictures of flowers from my own library such as Flower Painting (Robin Harris, Phaidon, 1976). And I looked again at the Internet. A listing for the Santa Clarita Valley Rose Society’s “Roses In Art” webpage describes the history of rose painting. It says that the 19th century was the heyday of rose painting, noting a fine example in the Glasgow Museum’s Burrell Collection, called A Pink Rose and a Yellow Rose or, alternatively, Des Roses dans un Verre à Champagne . It was painted by the French artist, Édouard Manet in 1882, the year before his death.

Manet was seriously ill with a rare nerve disorder when he painted Pink Rose/Yellow Rose. He painted some seventeen flower still-lifes, including this one, in the two years before he died at age 51. Many of these small paintings show oeillets (carnations), pensées (pansies), lilacs, peonies, tulips, pinks, clematis and roses, most of which were brought as gifts to the artist by his friends. These paintings probably did not require too much of Manet’s failing energy and they gave the artist “enormous pleasure.” They are lovingly reproduced, together with tributes by Manet’s friends, in The Last Flowers of Manet (Robert Gordon & Andrew Forge, Abrams, 1986)

I find it gratifying to think that Manet’s debilitating illness was the genesis of his flower painting. It strips the genre—in this case at least—of any hint of triviality or preciousness. The flowers he painted were given to Manet by caring friends when he was a semi-invalid. One writer described the scene this way:

“He was sitting up in bed, painting flowers—the gifts of his visitors—in glass vases, pinks, roses and clematis in water, which combined the limpid lucidity of Vermeer’s paintings of stems in water with his own unmistakable thick, creamy brush strokes. …These were his last masterpieces, fragile impressions of refracted colour and light.” (Sue Roe, The Private Lives of the Impressionists: Harper Collins, 2006), pp. 246-47). Not only was Manet able to paint flowers, but he was also able to derive great enjoyment—and, I would add, dignity—from the exercise.

Manet’s last days cannot have been easy. He died of tabes dorsalis caused by untreated syphilis and rheumatism, which he had contracted in his forties. The disease caused him considerable pain and partial paralysis due to a slow degeneration of the nerve cells and nerve fibers that carry sensory information to the brain. Toward the end, his left foot was amputated because of gangrene; eleven days after the operation Manet died.

Pink Rose/Yellow Rose was purchased by the Scottish shipping magnate Sir William Burrell in 1937 and, as part of Burrell’s art collection, was donated in 1944 to the City of Glasgow. Burrell donated money for a gallery as well, but he was concerned that urban air would adversely affect the collection. On account of delays finding an appropriate rural site, the collection was not permanently displayed until the 1970s.

The painting is a modest 13 1/2” by 9 5/8” (34.2 x 24.8 cm.) Manet has posed a crystal flute vase in which are placed a pink rose and a yellow rose, against a neutral greyish-blue background. According to the Glasgow Art Museum’s catalog, his “painterliness is evident in the broad brushstrokes he uses to convey the forms of the petals and the leaves.”

If the heyday of flower painting was the 19th century, and if Manet was a serious practitioner of the genre—to the point even of providing relief from a progressive, fatal disease—what better way to understand the challenge and the reward of painting flowers than by walking in the artist’s footsteps? To do this it is not necessary to copy or even imitate Pink Rose/Yellow Rose, but merely to start where Manet started: using the elements of his painting—the vase, the pink rose, the yellow rose, rose leaves and a neutral background—as the building blocks of a painting.

I cannot leapfrog over Coral Guest’s hurdles; my vase, my flowers and my background will not be the same as Manet’s, so I will still have to “consider … shapes in between the parts of the plant because the whole thing holds together as one.”

Nick’s model

Nick’s model

Photo: Nicholas Read

So I bought a similar vase at the local Goodwill. I went to the florist in Central Square and showed Mariou, the saleswoman there, Manet’s painting and said I wanted flowers the same as those pictured. Mariou sold me two roses, but said that it might be a day or two before they would be as open as the flowers in the painting (although you can, she added, accelerate opening by putting the flowers into warm water).

I brought all this back to my studio and set up the painting.

That’s when I started having problems. While I had elements of the Manet painting, the flowers were not the same size, not exactly the same color, and were not open in the same way; their leaves were configured altogether differently than those Manet painted. Try as I might, I could not contort the elements into a tableau of Pink Rose/Yellow Rose.

I then remembered that I had set out to do a painting of flowers, not a painting of a painting. I’m sure Manet would have said, let the flowers do what they will. It’s not about the result, but about the doing. Freed from the mistaken goal of copying, I could “look between the leaves and stem and the angle of the flower, [to the] particular, almost an arabesque shape.”

Nick’s painting, stage one

Nick’s painting, stage one

Photo: Nicholas Read

For me a painting is a two step process. First, I need to understand and set down in a general way the structure of the subject (which includes the darks and lights). Second, I need to understand and capture the surface (or color) of the subject. If I were merely copying the painting Pink Rose/Yellow Rose, Manet would have already taken the first step for me. A painting is two-dimensional; its structure has already been committed to a flat surface. But the buds of the roses, their stems and leaves, the vase, the water in it, and the surface on which they all sit are three dimensional objects. It is up to the painter to describe them in two dimensions.

Having set up the vase and flowers in my studio as shown in the photograph, I start to paint. On the first day, I lay in the basic composition, including the lights and darks that define the shape and structure of the forms, leaving off the yellow rose for the time being in the hope that it would open in a way that would be at least similar to that in Manet’s painting.

Waiting was not a solution, however. Flowers in a vase are already dead; water, light and temperature only keep them looking alive. After a day or so, waiting for a hoped for metamorphosis didn’t seem like a good idea. The bloom was opening (slowly), but the leaves were starting to go limp! So I proceeded with what I had. (I should have done this to begin with!)

Stage two

Stage two

Photo: Nicholas Read

The second is step is interpreting the surfaces. There are many. The rose petals are translucent and fine, with intense color and subtle shadow—very much like a baby’s face. The leaves are opaque, but they are veined and waxy. There is the vase also, with its smooth and patterned surfaces. And there is the background—artificial to be sure, but a means by which to focus the viewer and eliminate distracting details.. These elements all combine and contract to make a visually interesting composition and, hopefully, evoke something of the spirit of a vase of flowers.

But in painting these colors and textures, I ran up against a second problem: try as I might, I could not seem to capture the intense translucence of the roses in oil paint. For my pinks I would mix cadmium red, vermilion, scarlet lake, alizarin crimson and rose madder with white to come up with the elusive pink, whose shadows were purple, green and red. The yellows were challenging too. No combination—cadmium yellow light, cadmium yellow deep, cadmium orange, Naples yellow and yellow ochre—could evoke the intensity of the yellow rose, and the petals’ capacity to transmit light.

It is always a good idea when confronting a painting problem to see how other painters have handled a similar problem. I went to the library and checked out three books: Josephine Walpole, A History and Dictionary of British Flower Painters 1650-1950 (Antique Collectors’ Club 2006); Peter Mitchell, European Flower Painters (Adam & Charles Black 1973); and Wilfred Blunt, The Art of Botanical Illustration (Antique Collectors’ Club and Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew 1950). I also visited the nearby Boston Museum of Fine Arts. The MFA did not have many flower painting on display that day, but I was able to see a variety of solutions adopted by such artists as van Huysum, Gainsborough, Burne Jones, Fantin Latour, Alma Tadema, Dewing, LaFarge, Gaugin and Renoir. Paintings not on display but appearing on postcards in the museum shop included those by Heade, Hills, Redon and Matisse.

I was surprised by what I saw. Each example was expert, insightful, gifted and elegant, but very little of it came close to capturing the characteristics of a flower that has so baffled me. It was the light. It wasn’t there. I look again at the photograph. The same.

I imagine it is because paint and printing ink are opaque. When light meets the surface of the paint, it stops. The paint cannot emit light. Certain techniques will suggest the emission of light. The watercolors in the book I looked at, for example, captured the incandescent quality of flowers better than the oils. This is because watercolors, when applied in a wash, allow the light to pass through the paint and refract off the white paper and back to the viewer, resulting in an impression of luminosity. Oil paints can be applied in this way but the medium is inherently heavier and darker, so the same lightness is difficult, if not impossible to achieve. The old masters obtained a glow through the use of glazes. Thin layers of transparent color are applied so that the light passes through them to reflect off the under painting below. Most modern painting—including that of Manet—was painted all prima, however. That means that the artist has identified the color and matched it (or rendered his “impression” or it), and the identified colors collectively created an image with structure and light.

Aware now of these limitations (and feeling less inadequate), my painting moved quickly to completion.

Finis

Finis

Photo: Nicholas Read

All I can now say is that it represents my best effort to capture what I see before me. A flower painting is unique because of the intensity and type of color required, very different from that of, say, a dog or a ship. Even looking at different reproductions of Pink Rose/Yellow Rose, I never came to a clear understanding of what the colors in fact are. They were sometimes too yellow, something too dark, sometimes garish, sometimes mute. One would have to go to Scotland, I suppose, to identify them with any certainty.

But even then, would they be the same as the colors Manet painted? Color is not immutable. I recently looked at the glass flowers at the Harvard Museum of Natural History. As ingenious as they were, I was struck by how little life they had. Apparently they were for many years exhibited in natural light. This had probably faded them. Or maybe they were always that way. As has been suggested, even van Gogh’s flowers are less yellow today than they were a century ago.

Flowers are obstinate. They defy capture. They remain completely autonomous and unique, and cannot be reproduced in paint , glass, or even in words. Their moment of glory is also fleeting, and in that way became a representative of life itself. And that, I think, is the source of their allure.

And why a dying man might be drawn to them.

To capture so elusive a subject is a challenge indeed, and makes the words of John Ruskin completely understandable: “If you can paint one leaf you can paint the world.” (5 Complete Works, “Of Leaf Beauty”: Bryan, Taylor & Co. 1894, p. 61).

Comments

I read spellbound. Nick, the combination of text and images really conveyed your process.

I have a passion for pillow cases!

Great story Allen. I look forward to more recollections of your travels.