Human Flower Project

Search Results for:Kew

Paul Mckinney Singing Through The Soil

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Singing through the Soil

Allen Bush pays homage to one of his mentors—a Western North Carolina farmer who orchestrated crops and equipment, and sang gospel music, too.

Paul McKinney and his trusty 1949 Farmall tractor

Photo: Paula McKinney

By Allen Bush

Up Avery’s Creek and around Mills River in the North Carolina mountains, between Asheville and Hendersonville, folks love Paul McKinney. He is a good man, a remarkable man. He and his wife, Mary, own McKinney’s Small Fruits and have been partners in love for fifty-nine years. Paul is old school though not old-fashioned, except for his customary overalls. He stands tall, over six feet, a wise, handsome man who shakes hands as firmly as he strung barbed wire.

I lived a half-mile down the road from the McKinneys between 1979 and 1995. Paul came down to introduce himself soon after I arrived. It was the neighborly thing to do. I had bought 37 acres and started Holbrook Farm, named after my mother’s side of the family. They had come from Trap Hill, a few ridgetops away in Wilkes County. My retail mail-order nursery published a spring and fall catalog and shipped rare and unusual perennials across the country for fifteen years. I moved to the farm from Louisville, Kentucky, after a year’s training at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, England. The summers were cooler and the winters milder in western North Carolina. I was a suburban boy turned nurseryman, full of myself, but actually not quite sure what I’d gotten myself into.

Mr. McKinney worshiped Jesus, loved his family and made no pretense. He drew no distinction between sinners and the saved. He was fair to everyone, especially his newly arrived, suspect, bearded neighbor. I was young, had some backing – the support of a family and new wife – and fell into the might-be-saved-someday category. Paul and Mary McKinney had bought a small place up the road, two years before I arrived. They had little financial backing but never lacked for loving family or devoted friends.

A young Paul McKinney working a field with draft horses

Photo: Courtesy of Enka Voice

The McKinneys began their marriage on an 800 acre farm that Paul and his father sharecropped a few miles away on Avery’s Creek. After the Second World War father and son made a gentleman’s agreement with the landowner to turn forest into farm. Stump by stump they cleared land, nurtured their homestead and made a living for three daughters and a son. Over time, it was understood, the land would grow more productive, farm profits would be shared and the land would eventually become the McKinneys’. Paul says the landowner promised, “If we make it, the land will be yours.” He died thirty years later. His wife and son followed in quick succession. All bets were off. A handshake so long ago meant nothing this far down the chain. This mountain farm, so much a part of the McKinneys’ lives, was sold from underneath them.

Paul, then, fifty-three, downsized. He bought six and one-half acres on Fanning Bridge Road. The McKinneys were not going to be caught short again. He put-up a pole barn for farm machinery and a shed for a milk cow.

He took “public work,” as he called it, for the first time. Paul took a job a mile away at the North Carolina Mountain Horticultural Crops Station doing farm and maintenance work. At the end of the day he came home to work until the daylight dwindled. Paul, it could be easily said, “traded his bed for a lantern.” He and Mary tended strawberries, blueberries and blackberries that they sold pick-your-own, and vegetables that they canned and froze for themselves. He had some fine equipment stuffed inside the open-sided pole barn, but nothing he loved more than the Farmall that had been his first tractor, bought in 1949.

McKinney could grow anything, and did—shown here with a row Baptisia pendula

McKinney could grow anything, and did—shown here with a row Baptisia pendula

Photo: Allen Bush

Paul grew corn and cut hay on farm land he leased all around Henderson and Buncombe County but he looked forward to coming home. He loved his new place. There was never any hint at bitterness over the loss of the bigger farm on Avery’s Creek. Paul was peculiarly magnanimous in his outlook: life’s ebb and flow evens-out over a long, blessed life.

Strawberries and stokesias were grown to perfection by an artist in harmony with crops and equipment. Seeds of Stokes’ aster and baptisia were contract grown for Jelitto Perennial Seeds. I envied Paul’s practical skills. I had none. My father once said that, tools in hand, I was “like a bear with boxing gloves on.” (Paul McKinney astounded me with his know-how. He once poured Coca-Cola on a rusted chain and untangled frozen metal.)

Paul loved to sing gospel music. He and Mary never traveled far but they began going a day’s distance to meet other folks who enjoyed singing. And sometimes the group came to the McKinneys.’ They would gather to sing on the back porch after supper, surrounded by the majesty of this small place. You could hear Paul’s magnificent, deep voice down the road.

Comments

Mothers Remedies From Jamaicas Country

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Mother’s Remedies from Jamaica

It’s cold season. Georgia Silvera Seamans and baby Robert catch the bug and glean home remedies from grandmother. Fetch the cauldron…

A mobile for the baby’s room? No, it’s bitter melon (Momordica charantia), used in Jamaican traditional medicine to make a tea that eases stomach ache.

Photo: wiki

By Georgia Silvera Seamans

My baby’s ear infection went away without his taking antibiotics. Now, we both have colds. He is not being given anything for his cold except liquids and rest. I am gargling my sore throat with warm salt water per my mother’s instruction. This morning, after putting my baby to sleep, my mother told me about home remedies of her youth. My mother grew up “in the country” of Jamaica.

Fever

Pick a lot of fever grass (a.k.a. lemongrass), boil it in a large cauldron, pour the hot liquid into a tub, and set a wooden plank across the tub. The feverish person would then sit on the plank and be covered by a sheet. The person would remain under the steam sauna until the water became lukewarm. Prior to pouring the fever grass brew into the tub, a small portion would be sweetened with sugar or honey for the feverish person to drink.

Headache

As many cow-foot leaves (Piper umbellatum) as were needed to cover one’s head were gathered and then your head was wrapped with a scarf.

Wrap an aching head in Piper umbellatum (cow-foot leaves), a relative of our own root beer plant/hoja santa (Piper auritum)

Image: Nicolaus Joseph Jacquin

Cold

A weed whose name my mother cannot recall was boiled and drunken for a couple of mornings.

If One Stepped on a Rusty Nail

A paste made of kerosene oil and grated green banana was applied to site and the foot was wrapped tightly (bandaged) for a day. The nail would emerge from the wound and there would be no need for a tetanus shot.

Cut

The wound was cleaned with a mixture of bay rum and camphor balls and then wrapped with a bandage. This application would prevent an infection. The bay rum and camphor balls mix was something my mother’s grandmother always had in her house.

Tummyache

Cerasee tea, a bitter brew derived from the bitter melon plant (Momordica charantia) was sweetened and drunk by the person with a tummy ache. I recall drinking cerasee tea. Also, we had a plant growing along the fence of our side yard. The fruit is very beautiful. A stronger brew could be administered as a cleanser and was known as a “wash out.”

If a Baby Contracted Pink Eye

Dew gathered from leaves very early in the morning was applied to the eye. (An alternative was to apply mother’s milk to the affected eye.)

Note: Hope you’ve both made full recovery, Georgia! (Georgia’s weblog is Local Ecology.)

Comments

Georgia, I enjoyed reading about your mother’s “country” remedies,

That is one cute photo of you and young Robert!

I hope you all are feeling better very soon.

Allen: we are better, thank you. Mother/grandmother’s care was a major contributing factor.

Thanks .

Iris Stocksii Your Day Is Coming

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Iris stocksii: Your Day Is Coming

Alpine horticulturists around the world, including Allen Bush, wait with excitement as cultivation of a rare Juno iris, collected in Afghanistan, begins.

Tony Hall working on a frame of Juno Iris

Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, 2009

Photo: Jim Almond

By Allen Bush

I spent one sleepless hour after another on my London flight in late May walking the aisle while staring at an unconscious planeload. I tried to play catch-up. Two glasses of airline wine and an Ambien didn’t do a bit of good. A day later I came calling on Tony Hall cross-eyed with jet lag. Sleep walking for a couple of hours around the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew seems now like a dream—full of memories of a friend.

I tumbled out of the car on Kew Road at Primrose House and graciously agreed to be picked-up sooner or later. Later preferred. I feared sooner since neither Kew Gardens nor precious time with Tony Hall should be done on the fly. Hall has retired – sort of. He was for nearly thirty years the Manager of Kew’s Alpine Unit, caring the alpine plants and bulbs and overseeing the Alpine House and Woodland Garden. Hall, renowned for his knowledge of Iris, is the leading authority on Juno Iris and working toward a botanic monograph. Kew continues to provide facilities for Hall’s Juno Project.

Tony buzzed me in and was eager to get moving. A special package had just arrived: four bulbs and nearly fifty seeds of the very rare Iris stocksii.

Iris stocksii, a rare and genetically mysterious Juno iris, in its native Afghanistan

Photo: Juan Piek

Juan Piek, a South African, working for Security Forces in Afghanistan, found the Juno Iris in Kajaki, Helmand Province, and told Hall that he would put the collection in the mail. A month went by and Tony worried that it had gotten lost, but, fortunately, Piek had waited until he was safely home before posting the rare species. Piek was, according to Hall, “…a lover of plants, especially Proteas…not especially Junos.”

In a battled scarred desert landscape, Piek ran the risk of landmines and avoided the crosshairs of feuding warlords and resurgent local terrorist networks. At stake in Helmand is the rich opium crop. 40% of the world’s production comes from the Province, an area described by the New York Times as: ”…Afghanistan’s most dangerous land.” (Take a look at this video.)

There may soon be a land rush there, too, since an internal Pentagon memo recently suggested Afghanistan might become the “Saudi Arabia of lithium.” (Lithium is used to power laptops.) General Petraeus, Commander of U.S. Central Command (and just recently promoted), cited this vast reserve and other rich mineral deposits for its “stunning potential.”

Not quite lost in this land grab has been Piek’s prize, Iris stocksii, whose vital DNA is being mapped at Kew. The “stunning potential” of this species will soon power-up the fertile imaginations of a few talented botanists, molecular scientists and horticulturists, and, worldwide, there’s a handful of us who can’t wait to see what happens. We may have to wait awhile.

Tony Hall will try to try to mimic conditions indigenous to the dry, stony slopes of central and southern Afghanistan and neighboring Baluchistan, around Quetta, in western Pakistan—an elevation range between 1150-2700 m (3,773’ – 8858’). He’ll grow the Iris in special glass frames for many years to come, trying to coax them into bloom. In nature, Iris stocksii endures cold, dry winters and emerges with spring snowmelt, or the first rains, between March and April. After producing seeds, the plants soon go dormant again, surviving the intense summer heat(45 c /113 F) and prolonged dry period with the aid of fleshy roots and bulbs.

Longtime manager of Kew’s Alpine Unit Tony Hall (shown here before the Palm House, May 2010) is working on a monograph about Juno Iris, his specialty.

Photo: Allen Bush

Hall was chomping at the bit. He wanted to hand deliver the parcel to Kew’s Jodrell Laboratory, where Dr. Mark Chase, one of the world’s leading molecular scientists, would conduct a DNA analysis and add his findings to the matrix for junos. “Iris stocksii is such an important and morphologically unusual iris,” Hall emphasized. “It must be added to the tree.” We crossed the street into the gardens through the Shaft Yard Gate and wandered toward the Jodrell, past the Palm House and into the rock garden. We paused at the luxuriant, blue- flowering Iris cycloglossa. This tuberous, clove-scented species, native to Herat Province in Northwest Afghanistan, is more receptive to garden cultivation, perhaps because it grows in moist meadows, which is not usually the case with Junos. Tony told me it had – just the day before—been awarded the Royal Horticultural Society’s distinguished First Class Certificate at the Chelsea Flower Show. This was turning-out to be a big week for Juno Iris.

The new Alpine House at Kew

The new Alpine House at Kew

Photo: Richard Wilford

Just beyond the rock garden we stopped at the new Alpine House. The previous “new” Alpine House had been completed in 1979, when I was an International Trainee. Now it’s gone. (It seemed like only yesterday!) The Jodrell needed more room. Tony muttered something about missing the past two Alpine Houses (the earlier version, next to the Order Beds, now holds a bonsai collection). Tony, nostalgic for the past, shook his head and said great things had been accomplished in both these old alpine houses.

“I heard that, “ Kate Price barked back. Kate is growing good things, too. She is the Team Leader for the Alpine House and Woodland Garden. Tony knows Price is growing good things and tells me quietly, but not so she can hear. Price has just returned from North Carolina, a study trip not far from where I had been in the north Georgia mountains just a few weeks before. Tony Hall began getting antsy and excused himself, delivering the goods to Mark Chase at the Jodrell while I lingered in the Alpine House.

Kate Price, while hand watering, climbing among the landscaped rocks, looked over species that are a world apart from the temperate woodland plants of the Southern Appalachians. She described a few species she was tending in the Alpine House, choosing for rarity, rudeness and a good laugh.

“For rarity, the critically endangered and not enormously appealing Centaurea akamantis, from the Avgas Gorge in SW Cyprus, where it grows on near vertical, north-facing and permanently shaded walls,” Kate reported. “For sheer rudeness, the shocking dinner-plate-sized flowers, with flesh-pink, hairy interior to the spathe, of the Helicodiceros muscivorus, which emit an evil and powerful scent (said to mimic the stench of a rotting seagull chick) to attract pollinators to their Mediterranean sea-cliff habitat. For provenance (and comedy value), the smiley faces of the Calceolaria uniflora, from the wastes of Patagonia. The white ‘grin’ on their faces is a sweet structure, pecked at by birds, who then inadvertently pollinate the flowers as they move between them.”

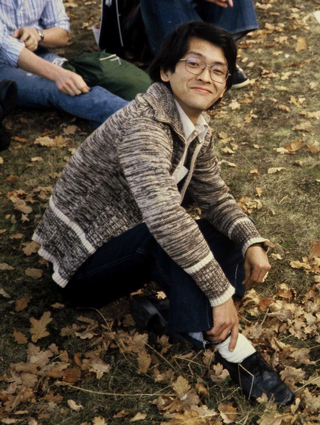

Takemi Iida, at Wakehurst Place, West Sussex, 1978

Takemi Iida, at Wakehurst Place, West Sussex, 1978

Photo: Allen Bush

Takemi Iida figures into this story. He is the reason Tony Hall and I keep in touch. Tony and I were acquaintances when I was at Kew in 1978-79 (International trainees were the lowest on the Kew totem pole) but we both shared a close friendship with Iida, a native of Japan, who was a Kew Diploma student. Iida was destined for greatness, but worked himself to death and died of a heart attack, home in Japan over fifteen years ago. The news didn’t settle well with either one of us. Tony and I have kept-up contact with one another, along with an occasional visit, to keep Takemi’s memory alive. Iida was a brilliant horticulturist who defied normal characterization. Disheveled in dress but a stickler for detail, he was precise with his hands (he enjoyed woodworking and knitting). He was self-possessed and well liked—a lover of Shakespeare, bound for tragedy.

Takemi would have loved this iris story. I can picture him, firing-up a cigarette and laughing at the obsessive foolishness that Hall will go through in order to bring this to bloom. Iris stocksii hasn’t been grown in cultivation in decades. All attempts have failed. Another Juno, Iris postii, took 12 years of coddling before flowering. Tony Hall knows it’s crazy.

It doesn’t matter. This rare species was plucked from the wild – truly wild Afghanistan. Tony might not finish the job but someone will. Piek’s prize was shared with Henrik Zetterlund from the Gothenburg Botanical Gardens in Sweden and a few other Juno aficionados. Hall knows that Iris stocksii will someday come into flower – for the first time in garden cultivation – somewhere. And Tony and I know Takemi Iida would be enjoying it all.

Rose and my friend arrived two hours later, just as I was finishing a pub lunch of cod, chips and mushy peas, on Kew Green, with Hall, at the Rose and Crown. “How’d it go?” I was asked.

“Well, there was this Iris…“

Comments

Reading this marvellous essay I was reminded of the the history of trying to cultivate the Persian Rose, Hulthemia persica. Jack Harkness quoted John Lindley of 1829: “It resists cultivation in a remarkable manner, submitting permanently neither to budding, nor grafting, nor laying, nor striking from cuttings; nor in short to any of those operations, one or other of which succeed with other plants. Drought does not suit it, it does not thrive in wet; heat has no beneficial effect, cold no prejudicial influence; care does not improve it, neglect does not injure it.”

Jack Harkness raise numerous hybrids in Hitchin in Hertfordshire in the 1970s.

Thanks very much John. I should try Hulthemia persica (Rosa persica), but it, and its progeny, appear as scarce as hen’s teeth in the trade—most likely for reasons Mr. Lindley made clear. Maybe all it needs is the interesting black spot preventative you mentioned in your May post? I’m on the look-out to see if I can hunt one down and tame the beast. I’ll keep you posted. Heavy thunderstoms expected this morning. I don’t think that’s part of the rose’s recipe…

Joe Pye Weed My Man

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Joe Pye Weed, My Man

It’s hotter than a boiled peanut! Time for the hard-core gardeners of the Mid-South—like Allen Bush—to show what they’re made of.

Joe Pye Weed (Eupatorium maculatum ‘Atropurpureum’)

stands tall in the July garden with Rose Cooper Bush

Louisville, Kentucky

Photo: Allen Bush

By Allen Bush

After two hours of weeding and planting in the sweltering morning heat, it’s usually time to throw in the towel. Well, not quite. I keep a towel handy to wipe the sweat off my creased brow and dab my receding hairline. This is one coping ritual for mid-summer. A cool swim later in the afternoon can work wonders, too. But the Lakeside temperature is hovering near 90 F (32 C). There’s no magic, there. When the morning temperature hits the low end at 80 F (27C), as the sun comes-up, you know you’re in for a rough ride the rest of the day. There’s no stopping 90 F (32 C) or hotter. During spells like this, when the humidity is as stifling as the debate on debt limits, it’s hard to catch a break.

July wasn’t hot straight the way through, and I wasn’t stuck in Kentucky all month, either. I caught a breather in the Colorado Rockies, with good friends, looking at alpine wildflowers in early July. My pals Kirk Alexander and Panayoti Keliaidis organized a great tour. I’d call home each day and Rose would tell me about the skyrocketing Louisville heat index that hovered in the triple digits for days. I tried to be sympathetic. The annoying heat index – a summer flogging by forecasters – combines ambient temperature with the relative humidity. But it doesn’t skewer “the hardware of reality.” It’s hot and we all know it.

I didn’t tell Rose I was wearing a cotton sweater at 10,000 on the road up to Pikes Peak. Nor did I dwell on walks through meadows in the alpine tundra filled with primroses and alpine forget-me-nots.

Nurserymen Richard Saul and Ozzie Johnson at the Saul Brothers’ Swamp location in Atlanta, July 2011

Nurserymen Richard Saul and Ozzie Johnson at the Saul Brothers’ Swamp location in Atlanta, July 2011

Photo: Allen Bush

At the end of the Perennial Plant Association symposium during the third week of July, I drove from Atlanta to Clermont, Georgia, to McMahan’s Nursery to visit my friend, the nurseryman and plant explorer Scott McMahan. It was plenty hot in Georgia, too. I seldom return from a trip without picking-up a few plants. I’d already broken the ice (I feel cooler mentioning ice….) a few days before at McMahan’s downtown Atlanta Garden*Hood and across town at the Saul Nurseries Swamp location.

When the temperatures rise above 90 F (32 C) normal retail garden center customers call it quits until the next spring. But the plant-obsessed keep on shopping and planting. At McMahan’s I kept piling-up my cart, and only at the verge of heat stroke pulled out the Visa card, double-stacked the plants in the car, turned on the air conditioning, and drove home on country roads through the mountains, bordered on either side by kudzu vines climbing-up trees along the forest’s edge.

Thank God for A/C. Interior in Louisville, late July

Thank God for A/C. Interior in Louisville, late July

Photo: Allen Bush

By the time the kudzu canyons started to dwindle and there were no more handmade signs pointing the way to “Boiled peanuts just ahead,” I figured I must have crossed into Tennessee. When I pulled-in the drive way in Louisville at 9:00 that night, the evening air was suffocating. The house windows were fogged-up.

I worked in retail from 1980 to 1995. Eager garden center customers would come around in April and May ready to fulfill magazine-stoked garden notions. In the ‘80s, an English mixed perennial border was the fantasy. Billowy white baby’s breath and towering delphiniums in breathtaking colors looked so easy and effortless in the great English gardens. It took years before Americans could think of the native Joe Pye weed Eupatorium maculatum ‘Atropurpureum’ as majestic, a peer of the statuesque English Delphiniums. For years, it had to be English. Puny 18” (45 cm) Delphinium statuettes in the south didn’t cut it.

Allen Bush with Lilium formosanum, a wonder of July in the Tophill garden, Louisville

Allen Bush with Lilium formosanum, a wonder of July in the Tophill garden, Louisville

Photo: Rose Cooper Bush

I tried to be consoling. When southern delphiniums died before Independence Day, I urged all blame be fobbed-off on the bloody British. I can’t be without Joe Pye weed and the companion, easy-to-grow, eight-foot tall (244 cm) Formosa lily. Lilium formosanum is too good to believe. And it self-sows and often flowers the first year.

“How much time do you want to spend in your garden, “ I would ask retail customers. The answer was always an enthusiastic, “As much as possible!” The customer has a pulse. The follow-up question —and often the deal breaker—was: “How much time do you want to spend in the garden in July and August?” The answer, the hard truth: “As little as possible.”

I could have sold a lot more plants if I’d treated the exercise like selling used cars. “You can’t go wrong. Plant perennials once and you’ll never have to plant them again. They’re no fuss whatsoever.” Woe is the home gardener who dared to ask me for a personal guarantee: “Will your perennials live forever?” It was a waste of time to offer all the obvious reasons why drought and pestilence might strike their plants dead by the time they got home.

Soleful potting at Garden*Hood, in Atlanta

Photo: Allen Bush

I stumbled-on a fool proof answer; it came pouring out of my mouth in frustration one day: “They’ll live if it’s God’s will.” No sense equivocating on this point. Nobody ever came back to challenge me. Or maybe the plants lived happily ever after—as God, not I, ordained.

Steering back from Georgia last week, my wagon was packed to the gills, leaves of my new plants pressing-up against the windows. A few motorists gave me the thumbs-up; most just stared and wondered. I came home with twenty-two trees, shrubs and perennials to plant. McMahan and his sidekicks Ozzie Johnson and Dan Hinkley had discovered a few of them on trips to Sichuan and Northern Viet Nam.

Scott McMahan and Tiffany Jones of McMahan’s Nursery, Claremont, Georgia, pack up the author for the trip back to Louisville.

Scott McMahan and Tiffany Jones of McMahan’s Nursery, Claremont, Georgia, pack up the author for the trip back to Louisville.

Photo: Allen Bush

I fell hard for Hydrangea aspera ‘Golden Needle’ that they collected near the town of Taoyuan. Even though Mike Dirr pays little attention to the species in Manual of Woody Landscape Plants, I have to think that it’s do-able in Kentucky if it withstands the Georgia summer heat. The lavender buds open-up to white mopheads. They found Lilium poilanei on another trip in the mountains of Northern Viet Nam, near the border with Yunnan. Scott said it had recurved, sweet-scented yellow blooms with red splotches on the insides of the trumpets. I grabbed a pot. (It’s the rainy season in the mountains of Sichuan and Northern Viet Nam. We could stand some rain, here, about now.)

Then there was Anisacanthus wrightii, the Texas firecracker – a perfect common name for my summer mood. I ignored the warning that it might be hardy to only Zone 7. Kentucky is zone 6 but hummingbirds love the plant and so it gets a shot. Same thing with the zone-challenged (zone 7) blue flowering Burmese plumbago, Ceratostigma griffithii. Blue flowers are as scarce in my garden as a cool day in July. The red tinted autumn foliage doesn’t sound too bad, either. I trust the Burmese plumbago, my little piece of the Himalayas, will be fine in Kentucky. God willing.

Comments

Sounds as hot as it was in NYC. We got rain two days in a row and hoping for more. Trees growing in concrete planters and in micro urban heat islands are stressed!

Lovely photo of Rose and the rosy-blossom Joe Pye Weed.

Thanks, Georgia. Glad you got some rain. We’re doing ok with a few lucky scattered showers, but Louisville had its third hottest July on record. August looks like more of the same. As they like to say in Georgia, “It’s so hot, even the bass have ticks.”

I have to admit, I have spent precious little time in my garden this last month. I keep getting distracted (and the mountains are so alluring, as you know!). Yesterday we left sweltering Denver (high: 96F): at the top of Mt. Evans, the frozen freshets were still topped with thick ice, and I feared the wind gusts at 40F would tip over my van. Felt good going back down tot he heat, I admit!

Homecoming Mum The Riot On Your Chest

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Homecoming Mum: A Riot of Conformity

How to stick out, fit in, and drop $75 for the big game.

JV cheerleader Amani Dorn sold programs

at Lake Travis (TX) High School

Homecoming football game, 2002

Photo: Bill Bishop

Lake Travis High School JV cheerleader Amani Dorn looks down at her chest, powerless to explain what’s there. “I guess it’s based on the whole corsage thing.”

She’s wearing a silk bloom the size of a cauliflower, nestled in spangles and rigged with a fake butterfly. Two pounds of trinkets hang from red and silver ribbons down to her bare calves. This is no corsage. It’s a dead grouse crossed with a bottle rocket, a Texas homecoming mum.

Depending on your feeling for the boys-will-be-hideous sport of football—chin straps, ice packs and necks thick as thighs—the homecoming mum is either the mightiest incursion or the ghastliest concession girls have made, our turn to shine and groan. At the Lake Travis High School Homecoming last month just about all girls over age 12 and under 25 arrived with chestwear. Outside the stadium one fan, obviously a mum-novice, stepped cautiously, steadying herself on a boy’s arm and lifting her gush of ribbons to keep from tripping.

“You kind of get to show off,” said Lake Travis sophomore Ashton Verrengia, standing with an armload of programs by the main gate. Her mum sagged from two oversized pins, loaded with a panda bear, globular heart, cut-out of the state of Texas, even a car, since “I’m going to be driving this year.”

Kira Miles, senior,

Kira Miles, senior,

with black and white mum

Permian High School homecoming

Odessa, Texas, 2003

Photo: Julie Ardery

Up in the stands, blonde and bronzed April Fields, also a sophomore, sported two gigantic mums, one a gift from her date, Brett Jennings, the other from friend Clayton Amacker, in the running that night for Homecoming King. Both her silk flowers bore Batman insignia because, she explained, “The theme is superheroes for homecoming.” April said “creativity” keeps driving the mum tradition to new extremes; to prove it, her two mums were studded with more symbols and cryptic allusions than a Renaissance altarpiece: “O” and “Pushpop” in silver lettering, a Batman yoyo and a soccer ball charm.

On Wednesday before the Lake Travis homecoming game, Glenda Morris, floral designer of the H.E. B. at Bee Caves Rd. and Hwy. 71, sounded edgy. “We’re booked solid. We can’t take any more orders.” Christy Cedeno, a clerk at the nearby Randall’s, said her floral department began preparing for mum season back in July. “We make them all summer long,” customizing each flower as orders flow in. Cedeno said her store had made over 150 silk mums for Lake Travis homecoming alone. Donna Parker, owner of Flowers by Nancy, Too in Lakeway, estimated she would fill 100 mum orders by game day, and “this year, we’ve added lights.”

Those raised in milquetoast states like Ohio or New York may think a homecoming mum is one white flower with a bow of your school colors and—oh, wow—a pipecleaner initial. Native Kansan Becky Swem, *with* flower wholesale house Pike’s Peak of Austin, remembers waiting on her first Texas high school cheerleader years ago, “I kept trying to convince her to get something else. She’s standing there in her little uniform and looking at me like I’m crazy. And I’m thinking, ‘Why does she want this huge mum and all this crap hanging off of it?’ ”

Why, indeed? Even old hands at mum-making, like designer Tom Blomquist of Bill Doran wholesale, aren’t sure, but he declares, “This is a Texas phenomenon. Nowhere else in the country is the football mum business like it is here in Texas.” As with most Lone Star excesses, the trail seems to lead toward College Station. Members of the Aggie corps used to buy their dates white chrysanthemums for every home game. Not to be outdone, the UT fans started wearing flowers, too, for the big Thanksgiving Day contest against arch rival A&M.

Dorothy Langston, a third generation Austin florist, sold fresh mums for her grandfather Joseph Brown’s shop back in the 1950s, toting “200, 300 football mums already dressed, down to UT stadium.” Langston says these corsages, made with fresh flowers, just had a ribbon and one long streamer. In 1959, her senior year of high school, Dorothy remembers a tiny football and a cowbell had been added to her homecoming mum. “It didn’t have all these other things, the helmets and the animals,” much less today’s riot of silver chains, music boxes, cowboy hats and wishbones. This year Bastrop Florist, for example, offers customers a menu of 118 gew-gaws. “All high school students want to conform at some level,” Donna Parker explains. “They want it to be just like everybody else’s but then they want it to be different. So we specialize in ‘just like everybody else’s but different.’ ”

Prices? Renee Dahl of A Bed of Roses, bracing for Bowie and Crockett high schools’ homecomings, says, “the basic Plain Jane starts at $16.95, but the average mum goes for around $35 to $50, and on up.” On up where? Well, figure you’re mixing football mania, peer pressure and Texas ostentation with teen sex hormones and a Chinese labor force. “It became a competition,” Blomquist says. “Who had the best, the most unusual, the fanciest? The sky’s the limit.”

Mother/Daughter florists Wanda and Micki Smith of Odesssa, TX

show mums they’ve made for local high schools rivals

Permian (black) and Odessa (red)

Photo: Julie Ardery

Sandy Smith, a designer at Bastrop Florist, said that in football-dazzled Abilene, she once assembled a maxi-mum reaching over the shoulder and around the waist, for $275. Aya Linenberger Matocha, owner of Bastrop Florist, reported that, “A lot of people come in and buy four and five—they’ve got that many kids in their family—and walk out of here going, ‘We’ll eat cold cuts the rest of the week.”’

The unofficial Queen Mum of Texas is Kathi Thomas, a wedding consultant who gives football mum demonstrations all over the country. In the years before silk flowers, she worked “literally all night the three or four nights before homecoming” to prepare 1000 fresh mums for Sam Houston State’s game. Now, “it’s rare to even see a fresh mum anymore.” Once upon a time, a girl’s corsage would shatter poetically on the way home from the dance. But poetry isn’t what today’s customers want. The new homecoming mum is built to last, a trophy of one’s high school years to hang on the bedroom wall. “The up side,” Thomas says, “is you can work far in advance. The down side is that it’s taking (mum business) out of the florists’ hands and into the craft stores.”

Hobby Lobby on Manchaca carries an aisle of mum trinkets and custom ribbons for 30 area schools. All you need is a stapler and a glue gun. Austin florist Ken Freytag calls the football mum, “a dwindling tradition” at least in larger cities. “In small towns it seems to still be thriving. Probably 15 years ago I would sell 400 to 500 mums for Anderson High School’s homecoming, and now we may sell 40.”

The megamum’s heyday, Kathi Thomas says, was the 1970s: “I student-taught at Crockett in ‘76 and there it was a prestige thing about how many mums you could get. Girls would have six, seven, eight on.” Around 1980, “We got very concerned about everyone’s ego.” Thomas cited and blasted the PC line: “ ‘Everybody doesn’t get ‘em so you can only wear one, because that’s more fair.’ Give me a break!”

Even tougher on the mum custom, Thomas says, was the passage in 1983 of House Bill 72, Ross Perot’s “no pass-no play” school reform. “It cut out all frivolity” in the school day and that meant “all of a sudden, you couldn’t deliver the homecoming mums to school.” Dorothy Langston agrees: “The schools said it caused too much disruption in the classroom because they would be jingling the cowbells every time the girls moved. So slowly it just faded out, about five or six years ago.”

But Bastrop Florist, Lake Travis High School homecoming and the crush of customers at Hobby Lobby tell a different story. The Tuesday before homecoming, Bastrop Florist was clogged with shoppers for both mums and garters (a mum-on-the-arm tastefully trinketed “for him”). Jeanette Vowell of Hobby Lobby says the mum custom has seeped from the high schools down to the junior highs and middle schools, even “to pewee football teams.” Fans are making their own chestgear with abandon.

Alanna Henry, Class of 2001, and custom mum

Alanna Henry, Class of 2001, and custom mum

Lake Travis High School homecoming, 2002

Photo: Bill Bishop

Alanna Henry from the LTHS Class of 2001 was all smiles attending the game with friend Sarah Smith, wearing a mum emblazoned—redundantly—with a smiling photo of Sarah and herself. “It means more when they’re not store bought, ” Stacey Dickerson insisted. Her homecoming corsage was a wilting canna leaf and sprig of lantana harvested from friend and fellow sophomore Jenna Hernandez’s yard.

Once the rah-rah-sis-boom-bah accessory of boy/girl dating, the mum has morphed. Designing, giving and getting are as complex as the rest of adolescent life circa 2002. Sharnisha Aldridge, a Bastrop 7th grader, is making her own first mum emblazoned in glitter with the names and jersey numbers of her brother, a player on the Bastrop football team, and her cousin Donovohn Henderson, who used to play for Bastrop but was killed last summer. Ashton Verrengia’s mum was made by “my ex-boyfriend’s mother. We’re still good friends.” Stacey’s backyard corsage incorporated the pin of another friend, a band member, “It’s a collaboration of, like, everybody.”

A corsage signifies, “Tonight, I am somebody.” But how do you signify “I’m a member of the Lake Travis drill team about to get my driver’s license and a soccer player on good terms with my ex”? To say all that is going to take a Texas mum and the chutzpah to pin it on.

(This story originally appeared in the Austin American-Statesman, October 2002)

Comments

My Mothers name was Dorothy Langston. Ran across your name in a search. Could you help me with information on the Langston name. I was adopted in March of 1948, LA Calif. Thanks.

This was a very interesting read. Thanks

The cheerleader.

http://www.ultimateguidetocheerleading.com

In Architecture Ancient Plants Grow On

By on February 28th, 2022 in

In Architecture, Ancient Plants Grow

Russell Bowes looks back several thousand years to the papyrus, palms, lotus and acanthus still rooted in the world’s building styles.

Stylized papyrus blooms top columns

Ramesseum—Luxor, Egypt

Photo:via wiki

By Russell Bowes

Ornamentation of a building is not strictly necessary. Doors, windows and walls function just as well plain as decorated. Yet for thousands of years, people have turned the structural parts of buildings into naturalistic and stylised depictions of local plants and flowers.

Was this for the joy in decorating plain surfaces? Or did the leaves and fruits have deeper meaning? Perhaps ancient buildings speak to us in a language we no longer hear, with words we no longer understand.

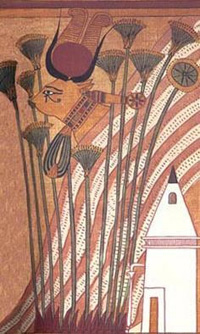

Goddess Hathor stalks through papyrus plants, from Papyrus of Ani

Goddess Hathor stalks through papyrus plants, from Papyrus of Ani

Photo: via wiki

The earliest Egyptian builders worked in a landscape inhospitable to trees. Thin soil, negligible rainfall and constant desert winds don’t support large stands of timber; thus, buildings constructed entirely of wood were extremely rare. In the millennia before the widespread use of stone as a building material, with wood at a premium and with relatively crude hand tools unsuitable for working what little timber was available, the ancient Egyptians used more abundant materials which were more workable with the tools they possessed.

The Egyptians staple building material was made from bundles of reeds, woven with palm fronds for added tensile strength and liberally smeared with layers of mud from the Nile. Palm leaves, however, are not completely flat but curve at the tip, and these curved tips were often left poking free of the structure at the tops of walls, forming a curved ‘architrave’ between the uppermost section of the wall and the roof. In centuries to come, when walls were made of stone blocks, this curve would be translated into stone, becoming the cavetto cornice which is such a distinctive feature of Egyptian architecture. Often painted to resemble a row of palm fronds, they served constantly to remind the later Egyptians of their architectural heritage.

Cavetto cornice, 204 Allen St., Buffalo, NY

Photo: Buffalo as an Architectural Museum

Wattle and daub, however, was not strong enough to support the roofs of later, larger buildings, structures with much longer walls than crude huts. Bundles of papyrus stems, which have a hollow structure similar to bamboo, were lashed together and interspersed with the wall panels or used as freestanding supports, although they also tended to splay at the top under the weight of the roof timbers. A crude column, complete with rudimentary ‘capital’ had been born. Again, when these columns were later rendered in stone, allowing buildings to become progressively higher, the architects copied the entire form of what had gone before—including the papyrus bindings. The column shaft was lobed in a literal translation of the bundle of stems, while the capital came to represent the closed buds of the papyrus flower.

In a society where practically everything had a symbolic meaning as well as a practical use, the closed buds came to represent “night”. Columns representing a single papyrus stem, with a fully opened flower—symbolising day and the rebirth of the sun god Ra—began to appear during the reign of the Pharaoh Amenotep III (1390 – 1353 BC). Similarly, the lotus column derived its form from a bundle of stems surmounted by closed flower buds. (It should be noted that ‘lotus’ refers to the white waterlily (Nymphaea lotus), from which the sun disc was, according to Egyptian belief, reborn each morning, and not the true lotus (Nelumbo sp.) which is not native to Egypt.) Both lotus buds and open flowers feature prominently in the capitals of composite columns, as do the flowers and buds of the papyrus.

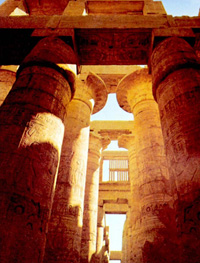

Hypostyle Hall, Temple of Karnack

Hypostyle Hall, Temple of Karnack

Photo: Artlex

All Egyptian architecture was of ‘post and lintel’ form, composed entirely of vertical and horizontal planes; the load-bearing capabilities of the arch would not become widely known for many hundreds of years. Because stone is stronger molecularly as a post than a beam, large numbers of columns were necessary to support comparatively narrow roof spans. This lead to the development of great hypostyle halls in the larger temples. With their brightly coloured lotus and papyrus columns, they represented the primeval swamp from which Hathor, the cow goddess, walked on the first day of creation. For the privileged few who could enter these halls, the architecture symbolized life’s beginnings of life, as humankind crawled from the mud beneath the sacred waters of the Nile.

Farther north, the climate of the Mediterranean coast, with richer, deeper alluvial soil and measurable rainfall, supported the growth of palm trees of sufficient size, strength and quantity to make them a viable building resource. Sacred to Ra, the palm was initially honoured not by a literal representation of the tree in stone, in the form of a column, but by binding palm fronds to a tall wooden stake, used decoratively to line processional routes and temple precincts. Again, the rope bindings were clearly copied when the wooden ‘trees’ became stone columns. A stone abacus block took the downward thrust of the roof rather than the ‘palm fronds’ themselves. Thus the plant determined only the form of the stone column it gradually became and not its supporting function within the structure.

The oak, Jupiter’s tree

The oak, Jupiter’s tree

Image: Alciato Book of Emblems

More temperate regions of the Grecian plains were more densely wooded also. Different species of tree were sacred to particular gods of the pantheon (the oak to Jupiter, the bay to Apollo) as well as the home of dryads (tree spirits) who cared for each tree and ensured its fruitfulness. Through their roots and branches, trees connected the earthly plane of human existence with the underworld and the heavens. In tribute to their deities, the ancient Greeks honoured the trees themselves – individually, as a single specimen, or collectively in the form of a holy grove. A grove may have been roped off to indicate its special status, and offerings of flowers and fruit were hung between the trees from ropes secured to the branches. It is not difficult to see the connection between tree trunks and columns, and thus between a sacred grove and a temple made of stone. Likewise, the swags of offerings were eventually translated into applied decoration, rendering the tribute permanent rather than transitory.

Once the grove of trees had been made permanent by reproducing trunks as columns, attention focussed on decorative treatments of their tops. It is not difficult to see the twin spirals (volutes) of the Ionic capital as representing the tight curl of an opening shoot, or a coiled stem [pic 9]. The most decorative architectural order was the Corinthian, the form most enthusiastically adopted by the flourishing Roman Empire. Although many variants of the style are known, the principal component was the acanthus leaf, symbol of death and rebirth. Both Acanthus spinosus and Acanthus mollis were represented. Being an herbaceous plant, the acanthus is an ideal symbol of regeneration.

Corinthian columns, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Corinthian columns, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Photo: Classical Traditions/Vanderbilt Univ.

Additionally, a popular legend added credence to the theme of resurrection. [pic 10] A young girl of Corinth died and her mother gathered together some of her daughter’s favourite possessions in a basket. Covering this with a tile to keep out the rain, she laid it on the child’s grave but in her grief failed to notice that she had placed it on a dormant crown of acanthus. The following spring, the newly emerging leaves pushed out from the soil and grew up around the basket. A passing architect, Callimachus, saw the basket enveloped by foliage and was inspired to use the composition as a column capital. A nice story, but one which will never be proved, unfortunately,

Usually Corinthian capitals were purely foliate, consisting of leaves of acanthus and other species. However, a variation, popular in central and northern Europe from around 2AD, shows faces peering down from the capitals, recalling the Greek idea of trees being inhabited by gods and dryads. [pic 11] Known as Jupiter Capitals, they may well have contributed to the popularity of the ‘Green Man’ mythology, a pagan deity of vegetation and symbolic of the links between the kingdoms of the plants and man. There was also limited use of the heavily stylised palm capital, showing that first the Greeks and then the Romans were not above borrowing ideas they found aesthetically pleasing.

The native flora of Egypt and Greece profoundly influenced the buildings each culture created. The effects were both stylistic and symbolic, with each country’s buildings honouring their gods and paying homage to indigenous creations myths. The Romans, having subsumed the forms of Greece into their own culture, with sometimes little or no understanding of the ideas that lay behind them, exported their adopted architectural styles around their empire. The use of the principal elements, in decorative terms, reappeared throughout time and around the world.

Bed with columns

Bed with columns

Photo: Chloe’s Garden Room

We continue to adorn our great public buildings with plant motifs and images which have little, if any, relevance or meaning for us today. But we feel comfortable with them, and unconsciously feel that a building in classical style is somehow more ‘solid’ in character than one without the familiar architectural references. It may be that, although the words have lost their original meanings, and the language is one which we no longer understand, the buildings still speak to us of the virtues of the past. Through the plant forms, obvious or disguised, that adorn our buildings, we continue to hear the messages spoken by our ancestors. We may no longer understand, but we are still listening.

Russell Bowes is a garden historian and lecturer, based in London. He’s generously appended a bibliography to this essay. Thank you, Russell.

Selected Sources

Anderson, W. Green Man (HarperCollins, 1990)

Fleming J., Honor, H., and Pevsner, N. Dictionary of Architecture (Penguin, 1991)

Gibberd ,V. Architecture Source Book (MacDonald Orbis, 1988)

Howarth, E. Crash Course in Architecture (Headline, 1990)

Lawrence, A.W. Greek Architecture (Yale University Press, 1957)

Lloyd, S. and Müller, H.W. Ancient Architecture (Faber and Faber, 1986)

Seton-Williams, V. and Stocks, P. Blue Guide: Egypt (A&C Black, 1993.

and Stocks, P

Wildung, D. Egypt: From Prehistory to the Romans (Taschen, 1997)

Woodbridge, S. Details: the Architects Art (Chronicle Books, 1991)

Yarwood, D. A Chronology of Western Architecture (Batsford, 1987)

Comments

I heart “classical” architecture. Now Russell has provided a possible reason: subconsciously I have been responding to plant-based forms.

Her Honor For A Potato Crop

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Her Honor for a Potato Crop

Should a community garden director be free to hawk her Olympic torch?

Route of the Olympic Torch, May 26, 2012

Image: London Olympics 2012

Sarah Milner Simonds was honored by the Olympic committee to carry the Olympic torch along part of its route to the 2012 summer games. Simonds, a 38-year-old horticulturist, was chosen for her work with People’s Plot, “a community allotment in South Acton [West of London], where we can grow our own fruit and vegetables, cook and eat the food we grow together.”

But before Simonds ever trotted her segment of the Olympic relay, her honor was besmirched: she had tried to sell her torch on ebay.

According to the New York Times, the winning bidder offered 153,100 pounds, ($242,323) last Sunday, meanwhile drawing down the fury many observers – though the unnamed buyer has yet to pay up.

Simonds defended her position, saying she intended to plow all proceeds from the sale back into People’s Plot: “There are still lots of people who feel strongly that these iconic torches are somehow sacred and that trading demeans their value,” Simonds said. “To these I would ask how exactly can we plant our potatoes using a torch? They obviously didn’t understand my motives.”

Several other torchbearers likewise have tried or are now trying to sell their Olympic flame-carriers, and most of them too have designated specific charities as beneficiaries.

Are honorifics transferable commodities? There are plenty of Olympic medals up for sale on ebay right now. Does it matter that Simonds didn’t win her torch, rather that it was conferred upon her by the Olympic committee? Since she didn’t have to toss a shot put farthest or run fastest for it, does that make the object any less hers to do with as she pleases, or more so? Do her charitable motives make a difference?

The American Academy of Motion Pictures Sciences confronted the problem back in 1950, after a trade in Oscars has begun. In 1950 the Academy began binding winners to an agreement banning them or their heirs “from selling their Oscars to anyone but the Academy for the nominal sum of $1.”

Academy Awards made prior to 1950 are exempt. Michael Jackson bought the 1939 Best Picture Oscar, awarded to “Gone with the Wind,” for $1.54 million in 1999. Other less renowned statuettes, all awarded pre-1950, have sold at auction too.

Sarah Milner Simonds of the People’s Plot, crowned with flowers and carrying the Olympic torch in Dunster, Southwest England, May 21.

Photo: Toby Melville, for Reuters

But back to Sarah Milner Simonds and her effort to convert the torch given for her work with the community garden into money to support that garden. Was she wrong to turn this status symbol into a commodity?

Initially we thought she was in the wrong. It struck us as demeaning to the games and a transgression of their ethics of amateurism and global friendship for one honored participant to exchange her bit of communal Olympic glory for a personal cause – no matter how many vegetables might result. The glory wasn’t hers, really. It belonged to the games, which generously had shone a light on her worthwhile endeavors. It was as if she were taking the ball and going home with it herself. Bad sportsmanship!

But then we noticed another detail in the Times story.

“Most of the torchbearers who participate in the relay were nominated based on work in their local community or an inspiring personal achievement. They are given the option to purchase the torch for $314 (in advance of their run) to $339 (day of run).”

This arrangement changes the dynamic considerably. It was not Simonds who first commodified the object but the Olympic committee itself. Since the committee failed to make Simonds’s torch a free gift, rather sold it to her (granted, for a very low price), she was within her right to resell it.

Tacky, yes. But unethical, no. We hope Simonds’s ebay buyer comes through and the People’s Plot prospers for years to come.

Comments

Interesting story. I wonder what would have happened if she waited until the Games were over…

Hfq 6 Fit For Foraging

By on February 28th, 2022 in

HFQ #6: Fit for Foraging?

Georgia Silvera Seamans, local ecologist of Berkeley, California, writes:

Spotted this vine with fruit over the weekend. Reminds me of a mango but as an avid mango eater (we had two mango trees in our back yard in Jamaica) I know it’s not a mango (tree!). I am hoping it’s human-edible so I can forage to exchange with Forage Oakland.

Hanging fruit in Berkeley’s Elmwood neighborhood:

Photo: Georgia Silvera Seamans

No popping off on this Human Fruit Query, folks; Georgia’s considering not only eating this herself but helping her neighbors to some also, through this interesting Bay Area group. Seems that they come together around the usefulness of local plants, much like the amazing Scooter Cheatham and Lynn Marshall here in Austin. (In the past, Scooter and Lynn have hosted “weedfeeds”—potluck meals where all the dishes are made from wild plants).

At right is a close up of the fruit. Anyone know it? Anyone digested it?

At right is a close up of the fruit. Anyone know it? Anyone digested it?

We did some digital grazing and learned that on Oakland’s east side there are many fruit trees, originally planted by Italian, Greek and Portuguese families who baked and canned and jammed the produce.

“People are too busy and too tired to pick peaches or peel, slice, core and stew apples,” says the Oakbook. “The problem is—no one told the trees, which means—the fruit still falls in the backyards. More often than not, it rots.”

In 2007, a group called PUEBLO organized and hired a few teenagers to pick the fruit and bike it to nearby senior citizen centers. The program was such a success its first year (harvesting more than 350 pounds of apples, plums, peaches, citrus and pomegranate) that in 2008 the number of pickers was doubled. So far as we know PUEBLO will harvest and deliver again this summer.

Georgia, these folks probably could tell you just what this vine is. And we’ll take a stab at it, too.

Banana passionfruit flower

Banana passionfruit flower

Passaflora mollissima

Photo: Quimbaya

Did you happen to catch sight of any of these gorgeous flowers? Our best guess is Passiflora mollissima, banana passionfruit. Purdue’s site offers some tasty specifics about how banana passionfruit is enjoyed in South America: “The pulp is eaten out-of-hand or is strained for its juice, which is not consumed alone but employed in refreshing mixed cold beverages. In Bolivia, the juice, combined with aguardiente and sugar, is served as a pre-dinner cocktail. Colombians strain out the seeds and serve the pulp with milk and sugar, or use it in gelatin desserts. In Ecuador, the pulp is made into ice cream.”

This Hawaii-centric site is less jovial: apparently Passiflora mollissima is considered an invasive plant in the islands.

We’ve spotted a number of banana passionfruit photos taken in the Bay Area, including several shots from the San Francisco Botanical Garden. We’ve also learned that there are a lot of passionfruit varieties out there, many of them yellow. And we could be way off. Please ask an expert before biting down.

We hope to hear from aficionadas of passionfruits, frigid fruits, and other quasi-edibles before Georgia’s foraging gets “out-of-hand.”

Comments

It seems to me that you are right, common name in Ecuador is “taxo” I guess that due to climatic factors the fruit is not ripen in the plant (turning yellow).

Our expert friends think it is Passiflora tarminiana. See the comments on <a href=“http://agro.biodiver.se/2009/03/do-you-know-this-fruit/”>this post</a >.

Passiflora sp. is my guess, too.

Ahhh foraging… we do a lot of it here in Sarasota, Florida, where you would think residents would be more interested in eating their tangelos, carambolas, papayas, & passionfuits than in watching the squirrels and racoons get them.

With so many people lining up at the food-banks, it’s amazing to us that we don’t see more people trying to gather the fruit-fall in their own back yards—to share, if not to enjoy themselves.

This discussion reminds me of another fruit ripening right now; it’s one that even long-time Florida residents seem to ignore: loquats, aka Eryobotria japonica. Tartly sweet, with many of the same flavor notes as apricots or plums,loquats are absolutely delicious and easy to pluck and pit.

In Turkey, cooks grill loquats with lamb—on skewers—just as we add peppers and onions to our kebabs. (A bunch of my people will be touring Turkey this April & May with National Public Radio’s Ketzel Levine as she explores the botanical bonanza of flowering bulb plants in the Aegean region.)

Even if you don’t yet have a taste for loquats, but if food and plants grab you—- check out Turkey, a forager’s heaven:

http://hollychase.com/ketzel-levines-botanical-tours/

Thank you Julie and HFP/ HFQ readers! I am pleased that the fruit is human edible. I wonder: does the fruit taste like a banana?

P.S. Hello Holly. Loquats are ripening in Berkeley, too.

Give Me Land Lots Of Land

By on February 28th, 2022 in

‘Give Me Land, Lots of Land…’

Flower farming, a venture with promise in Africa, is stagnating in many nations as “land reform” runs aground. And there are other high hurdles ahead.

Zimbabwe lands

Source: FAS/USDA

As recently as twenty years ago, Africa’s flowers were minor leaguers in the global flower market. That’s not so today, as Kenya (principally) but now also Ethiopia and more southerly African countries plow ahead. They hope to best South America and China by likewise capitalizing on sunshine, cheap labor and open land.

But whose land is it? Confusion and, in some nations, violence over that question have made flower farming enormously risky business. Brigitte Weidlich’s story of a cut flower operation in Namibia is fresh, and representative. She writes of the Wiese family’s 90 year old farm, Ongombo West near Windhoek, which once “exported arum lilies to the Netherlands worth several millions of Namibia dollars annually.”

In 2004, it was the first farm to be expropriated by the Namibian government, after a labor dispute. The white owners had to relinquish their rights to the property. In the years since, according to Weidlich’s report, the farm has been idle; “all infrastructure, including the large green houses for the defunct flower export business, has deteriorated.” Six “erstwhile farmers” who were resettled there to work the land have had to hire out on neighboring farms. And now the national Ministry of Lands has posted a want ad, hoping to attract “experienced and reputed engineering companies for the assessment of rehabilitation required for existing irrigation infrastructure.”

A Namibian official calls the situation at Ongombo West “a delicate issue”—another way of saying “big flat flop.”

In Zimbabwe, resettlement has been crueler. Land reform began with the election of Robert Mugabe in 1980. Britain, the former colonial power here, pledged 630 million GBP to implement a “willing seller, willing buyer” approach to land redistribution. Problems began right away and intensified with each passing decade. White farmers were not “willing” to sell; then, the Mugabe government gained first right to purchase available lands, but could not afford to do so. Agricultural production, further hampered by drought and rising fuel costs, stagnated.

In 2000 Zimbabwe voted on a new constitution that would have permitted Mugabe’s government to take lands away from white owners without compensation: i.e. expropriation. The referendum was defeated. But after the elections, pro-Mugabe forces decided to carry out their version of “land reform” anyway. They began forced “liberation,” taking about 42,000 square miles of white-owned lands.

“It is clear that the land resettlement program has been an economic disaster, with dramatic drops in agricultural productivity and economic growth,” writes Markus Scheuermaier.

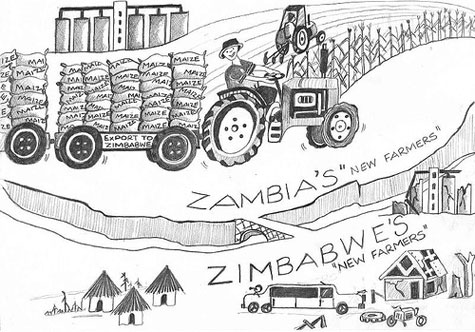

Cartoon pointing up Zimbabwe’s corrupt “cell phone” agriculture, dominated by elites, while Zambia’s farmers, many of them displaced from Zimbabwe, thrive.

Image: Sokwanele

African rights cannot overreach human rights, he contends. But this is just the most obvious flaw in Mugabe’s version of land-reform. Scheuermaier looks as issues of practicality as well as justice. Once an exporter of food, Zimbabwe has not been able to feed its own people since 2002. “In March 2004, an estimated 7.5 million people (or about 60 percent of the population) were dependent on food aid provided by the international community,” he reports. “Agricultural production has collapsed, and where land has been allocated to peasants the government has failed to provide inputs to allow them to sustain production on their new plots. Owing to poor rains, many have since abandoned their plots, and commercial farmers have not returned, fearing intimidation and violence.”

Meanwhile, South Africans have been monitoring Zimbabwe’s gruesome example closely as they, too, work toward land reform.

“At the onset of democracy in 1994, some 87 percent of (South Africa’s) agricultural land in the country was owned by whites, who make up less than 10 percent of the population. Thirteen years later, around four percent of land, or four million hectares (nearly 10 million acres), have been transferred to blacks.” The South African government has “promised to redistribute 30 percent of white-owned land by 2014.”

How will that happen, safely and fairly?

A bill that would have allowed the South African government to expropriate property from whites and turn those lands over to black South African farmers failed last week. White farmers are, of course, jubilant. Now, how will the promise be kept?

Economists, agronomists and policy-makers at the Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies are at work thinking options through, at least in the abstract. But hunger, land and, for that matter, flowers are not abstract, and making the leap from public policy to political reality is daunting, as Zimbabwe’s example proves.

About 150 years ago, Karl Marx was working on the same problem, also in the abstract:

“Centralization of the means of production and socialization of labor at last reach a point where they become incompatible with their capitalist integument. Thus integument is burst asunder. The knell of capitalist private property sounds. The expropriators are expropriated.”

All right. But then what happens? Considering the flower industry, a small but growing sector of southern Africa’s agricultural economy, both Marx and well-meaning 21st century scholars (Communist or not) typically fail to consider two crucial features of commerce.

First, it always takes intellectual capital to turn “means” like sunny land into productive use. In Zimbabwe, notably, the first lands “expropriated” were handed over to urban bureaucrats. What would they know about blackspot on roses?

There is evidence that traditional farmers, small shareholders, have managed some success on these newly acquired lands, despite all the forces against them in Zimbabwe. “This could be because they farm in more labour intensive ways and are less dependent on purchased inputs and fuel which have been in short supply because of wider economic problems,” writes Ben Cousins, director of the Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies. Cousins says these small land-holders have done especially well with cattle herds.

Cattle farmers, near Paul Roux in the Free State, South Africa

Photo: Aquila

They’ve been less successful in highly capitalised sectors of farming, or, Cousins says, “where long-nurtured market relationships have been undermined, such as in the tobacco or horticulture sector.”

In other words, it’s not just land, inputs and training that are lacking in southern Africa—but social capital. The flower market, more than most others, has historically functioned as a fairly tight-knit business, dominated as we all know by the Dutch. One of the most powerful investigations of this strange and beautiful commodity’s inner workings is Alex Strating’s study: “Kinship, Family and the Flower Trade in a Dutch Community.”

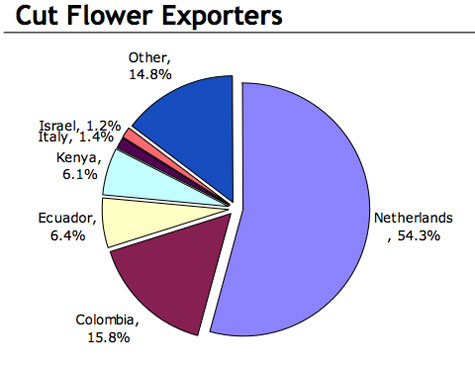

Global flower exporters by value ($5.7 billion market), 2005

Source: International Trade Center

Though Strating concentrated on the town of Rijnsburg, in the Netherlands itself, his study of closely-held firms there offers revelations about the flower industry as a whole. Through generational chains, family members (most of them male) pass along secrets of the trade. They also train novices in the multi-tasks involved—buying/packaging/transportation/sales—and can safeguard the names of their customers. Furthermore, Strating found that the tight ties of these lijnrijders made it possible to withstand the inevitable seasonal vagaries of this business – the crush of holidays followed by lean months, and, always, calamities of weather. Family members tended to be more willing to take pay cuts during hard times or stay after hours when orders flooded in, working along with the peculiar rhythms of the flower business.

This is not to say that such knowledge and social circuitry don’t exist in Namibia or South Africa or Zimbabwe. For in some respect, they must. But these are “means of production and socialization” that don’t come quickly or easily. And they sure don’t just happen with a windfall of property, whether that’s called “liberation,” “expropriation” or “land reform.”

Comments

An excellent essay. The inclusion of Marx is genius. Not to bring US politics to HFP, but the recent mocking of community organizing is nonsensical. One of the goals of organizing is to develop social capital. Social networks work as you brilliantly highlight with the example of the lijnrijders.

Garden Going Since Before Gardens For

By on February 28th, 2022 in

Garden Going Since Before ‘Gardens For’

Revisiting nurseries and public gardens, John Levett catches sight of Henry James but still hasn’t found “The Pottering Garden.” If you have a map to it, .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address) in Cambridge, England.

At Cambridge Botanical Gardens

At Cambridge Botanical Gardens

Photo: John Levett

By .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

Since when did the thought of going to a garden bring about palpitations of anticipation? Not recently? Not since the last time? Err…about 1984? Well, sometime around then. Or maybe it was just the last time when the arrival matched the picture in the head. Maybe I’ve had enough of gardens. Not gardening (although I start to flag this time of year). Just other people’s.

I was walking with a friend around Docwra’s Manor just outside Cambridge last year and realised it was the walkin’ and the talkin’ that made it and the thought of ‘this is the sort of place you get cream teas with scones and clotted cream and homemade blackcurrant jam and sticky fingers and nuclear strength tea imported in wooden casks from the Empire’ (it wasn’t).

Similar thing the year before. A friend was house-sitting for the Summer somewhere on the river near Hemingford Grey and would I fancy coming over for the evening and I did and it was The Manor where Lucy Boston had written the Green Knowe books. It was late evening and chilling up and friend’s dog went missing and so did I on the search and walking through the garden silence gave grounds for belief in the underworld.

Similar thing the year before. A friend was house-sitting for the Summer somewhere on the river near Hemingford Grey and would I fancy coming over for the evening and I did and it was The Manor where Lucy Boston had written the Green Knowe books. It was late evening and chilling up and friend’s dog went missing and so did I on the search and walking through the garden silence gave grounds for belief in the underworld.

So back to 1984, which had the best of times. And Ingwersen’s Nursery down in Sussex. For reasons now lost I’d got a passion for alpines. Read the books, bought the troughs, got the greenhouse (Yes! I know it’s not the same as an alpine house but it could pass for one!), seed from the Caucasus and points east sown but I wanted Instant Alpine and Ingwersen’s looked like it had the pedigree.

It was early April, bright, frosty, dawn. I drove down the A1, cleared London passing a ‘Troops Out’ protest in Parliament Square (Ireland in those days) and ate breakfast of salmon sandwiches at Biggin Hill overlooking the Weald listening to Johnny Mathis singing ‘Stardust.’ It’s still that clear. Ingwersen’s wasn’t a let down. They had the troughs and the alpine houses and the stone outcrops and the miniscule flowers which looked just like the illustrations and a steam railway at the bottom of the garden. It only needed three children in buttoned-up costume and their mother gathering her skirt and an old gentlemanly gentleman and ‘They were not the railway children to begin with.’ The thing I can’t recall is how much I spent. Guilt and memory consorting.

From that moment that nursery came to be a special place. Mustn’t go there too often then. So I didn’t but when I did it was always the first Saturday in April and the start time and the route and the salmon sandwiches on Biggin Hill stayed the same. Going back to special places needs its routines and its history. Then going back’s past its time. My last visit reminded me of what I knew—place has to do with time and how we were then and who and what was in our life.

Kew Gardens is like that for me, too. My mum, gran and me were always going to go to Kew for a day out but we never did. Gran died, then mum, by which time Kew had taken on myth. I got there in 1988 when life was spiritless and a friend called and said ‘Here’s a day out.’ We had lunch at The Old Rangoon near Hammersmith and thence to Kew but for my life then it was Hardy’s heath or Bronte’s moor at their most bleak. I arrived back there last year to see the new alpine house. Closed for repair, so I walked through the trees and sat by the Thames at Syon Reach, out of the crowd’s way, read and slept.

Cambridge Botanical Gardens

Cambridge Botanical Gardens

Photo: John Levett

I had similar feelings last week. I had a morning when I wake up and think ‘I’m closer to death than I was ten years ago so why am I spending time doing this’ and then restructure my morning accordingly but fall off the plan at half-past-one and take the (metaphorical) dog for a walk. To Cambridge Botanical Gardens. I’ve lived near botanical gardens (or ones that look like them) throughout my life and can see the Nineteenth Century point of them and they make sense in the current epoch when seen as places of work but I’ve never got much fun out of them. Which meant that I turned up there with a strop on. (Going places annoyed at the thought of being there is a part of me I should deal with.)

History first. Darwin learnt there and C.C. Hurst speculated there on the origin of the rose. Enough.

I got taken with incidentals—the age of one to whom a seat was dedicated (forty-four’s no age to die); the noise of grass cutting, tree felling and traffic on Trumpington Road; a cat stalking ducks; a group of day-trippers tripping from bed to bed; yet another alpine house under renovation. And gardening as an industry.

It wasn’t so many decades ago that I used to stop off at the Rose Society’s gardens in St. Albans on my way home from a day’s teaching, shattered and in need of head-space; hardly a soul around; seats and beds and acres of island. Standing-room only now. Last Thursday it touched me that I’d become a Larkin-like mitherer—the crowds and the prams; the intrusions of working days into one’s own day; the concessions to the current public taste. Maybe it was the acknowledgement of the current zeitgeist that we have to be gardening ‘for’ something—the Dry Garden (no watering required), the Fen Garden (repopulate the wetlands), the Winter Garden (no time off for good behaviour elsewhere in the year), the Fragrant Garden (now with wind chimes).

The Pottering Garden? I couldn’t see it. The one where you walk about clipping a bit, thumb-in a cutting, layer a trailer, scrape a space for some bulbs, shift this to there. I passed the ‘listers’, secretary-like with pen and pad, readying for the raid on garden-centre, website and Tesco. Clear the space, break the pot, heel in. Sorted ‘til the next generation. Like decorating a room.

Towards the end of the afternoon I walked out towards the far edges of the garden to where the staff were finishing off. There was a young lad there, maybe late teens, maybe an apprentice. I remembered leaving school in 1960 aged fifteen. There were three employment options open—metalwork, carpentry and gardening. It was still (just) the age of ‘a job for life’ and there were still lads who’d go into gardening, maybe in the municipal gardens, maybe on an estate, and stay there for the duration and into a pension. I wondered if this lad tidying up the beds of hardy geraniums, wiping off his tools, collecting the scattered pots would still be hoeing fifty years hence, not rushing but giving plants, and himself, time.

Cambridge Botanical Gardens

Cambridge Botanical Gardens

Photo: John Levett

I was going through one of my periodic ‘Modern Times’ moments—remembrances of gardens strolled through by Barbara Pym characters and maiden aunts with grans. Then, for reasons unknown, thought of Henry James. James furnishing Lamb House in Rye; choosing plants for his walled garden as he chose furniture for his rooms; matching foliage to brick as he would tapestry to panelling. Then I thought of him arranging his papers and his pens, his shelves, his working ways with his views, his chairs with his fireplace, his comfort with his protection.

Then I thought ‘just like me’. The garden as comforter. I reflected on how I arrange my chairs around my garden; the morning site, the mid-morning-coffee site, the lunch-time-snack site. How the time must be ‘just so’ to catch the sun above the warehouse wall (no problem for James with that one!); the annoyance of next door’s children out early on Sunday (very Henry); saving the un-read article to partner the cake-treat from Fitzbillies (how to explain that, should he be seen?) My garden for me is the pair of slippers, the useful cardigan, gloves that fit, Marty’s recliner, Norm’s bar stool. Sometimes ‘the garden for the bone idle’; other times ‘the GWF Hegel garden’; in my mind’s eye ‘the John Cassavetes garden’ (think scripted but improvised); never ‘the Princess Diana bring your lame and sick garden’ (ten years and still no miracles?).

I walked towards the exit in late sun and met a couple sitting near the water garden; a daughter and her father who was working in the gardens at the outbreak of war in 1939. I thought of a conversation with him but thought better; he looked tired, or lost elsewhere. I left with a pleasantry and went looking for tea. I snuck something out and sat in the part of my plot known as the woodland garden—nine square metres underneath next door’s tree, next to my ferns and R.Davidii with its autumn heps. There was probably noise. No mithering.

Comments

There is always good feeling after reading John’s writing…

The gardens look so green and the air smell so fresh..and the books!!

we do have many great gardens in Calcutta.

But sorry to say most of these gardens are no longer being valued. All in poor state.

The only upkept one may be Victoria Memorial Hall.

May be the present generation no longer have time to enjoy the morning dews… for they sleep late and wake up at noon time!

Anyway, John, these are for you…

The once, “Jewel in the crown”… left behind by the British.

http://www.asiarooms.com/travel-guide/india/kolkata/parks-and-gardens-in-kolkata/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_Botanical_Gardens

http://www.victoriamemorial-cal.org/

http://www.asiarooms.com/travel-guide/india/kolkata/parks-and-gardens-in-kolkata/eden-gardens-kolkata.html ( this garden is closed for reasons best known to them..Between the Forest Dept and the Army; Forte Williaom, over the gate entrance fees!) otherwise a nice garden where I go for my daily morning walk.

sandy.

opps!

it’s fort william !

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_William,_India

Last time I checked, Fort William was also in the mighty Scotland. Perhaps there is also a Fort William in India – great blog post nonetheless. Thank you for the read!

It’s really nice to read your John’s journey.

I myself also always try to visit city garden when visiting a new city.

Seems like a *hand*shake should be meaningful in farm country. Glad it worked out for Paul and Mary on Fanning Bridge Road.