Human Flower Project

Street Trees: Let’s Think Outside the Wires

Local Ecology’s Georgia Silvera Seamans explains why, in choosing a city’s trees, there’s a lot more to consider than power lines.

Hawthorn tree in bloom: short, showy, and nectar rich

So why isn’t it a choice of Oakland’s city foresters?

Photo: Georgia Silvera Seamans

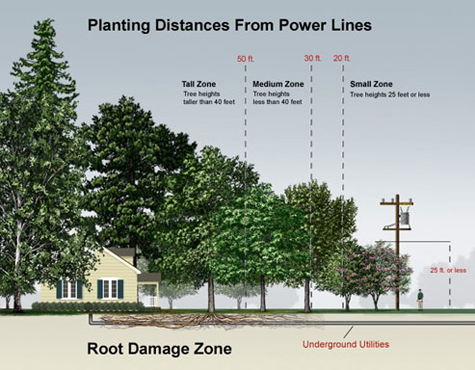

In urban settings, human tensions arise over the selection of large stature or small stature street trees. The “Right Tree in the Right Place” planting policy recommends that short stature trees – 25 feet or less – should be planted beneath utility lines because the canopies of these trees do not interfere with overhead wires. But emphasis on height alone neglects larger issues—of ecosystem value.

Large stature trees—like red oak, London plane tree, or sweetgum—do interfere with overhead wires, but they also provide greater ecosystem benefits than do small stature trees: they sequester (store) more carbon, filter more particulate matter from the air, and intercept more rainfall via leaves, trunk, and soil (and slow runoff into storm drains). And, because of their larger crown spread and evapotranspiration capacity, larger trees cool larger areas of surrounding air (cooling nearby infrastructure and buildings, too).

In a study of Berkeley’s street tree canopy conducted by the USDA Forest Service Center for Urban Forest Research (CUFR), researchers found that city trees saved $12.58 per tree in annual electricity costs. As for capturing stormwater runoff, the average street tree intercepted 1,478 gallons, a value of $5.91 per tree annually. The researchers also found that, overall, larger stature trees provided the most benefits: the average small, medium, and large deciduous street tree produced annual benefits totaling $32, $79, and $96, respectively. (Note: Author Georgia Silvera Seamans, assisted by Qingfu Xiao, research scientist at UC Davis, obtained this information as part of a research grant with Urban Releaf.)

Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba): as with many large trees, its flowers aren’t showy

Photo: Georgia Silvera Seamans

Though not all short stature trees have showy floral displays, they tend to have larger, more conspicuous flowers. Most people think of herbaceous perennials as the plants that attract bees and butterflies, but flowering trees are definitely popular with wildlife too. As cities make tree selections, they should consider the “wildlife-value” of species that produce fruits, seeds, nuts, catkins, and acorns. A tree’s wildlife-value in the larger ecosystem, something not usually quantified, involves its floral services for small, highly mobile species like butterflies and bees and some birds. Hummingbirds, for example, utilize showy flowers for nectar. As well, floral displays attract insects on which non-nectar eating birds rely. Not only are the showy flowers of shorter stature trees attractive to birds and bees, their exuberant flowering draws “oohs” and “aahs” from us humans. I have never visited Washington, D.C., in the spring, but I have heard the buzz about the mass blossoming of the Mall’s 3,000 cherries. (At this year’s San Francisco Flower & Garden Show, the USDA Forest Service created an urban forest garden. The sign below the coast live oak, interestingly enough, listed the aesthetic monetary value of the oak over 40 years as $5,210.)

Given the dual appeal of short stature trees, I was curious to see which varieties municipal urban forestry departments selected. A natural choice for a case was the City of Oakland. I am an intern of urban forestry issues for the City of Oakland Mayor’s Office. Oakland’s street trees are managed by its public works agency. The city’s Official Tree Species List, as of November 2007, has a limited palette of small stature trees. The list contains seven species: Strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo), Eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis), Crape myrtle (Lagerstroemia indica), Photinia (Photinia fraseri), purple leaf plum (Prunus cerasifera ‘Thundercloud’), Evergreen pear (Pyrus kawakamii), African sumac (Rhus lancea), and Water gum (Tristania laurina ‘Elegant’). Many of Oakland’s residential streets are lined with overhead utility wires, so I expected a longer list of short stature trees.

Of these seven species on Oakland’s approved street tree species list, four have documented wildlife value. According to the USDA Forest Service Silvics Manual of North America (1990), the eastern redbud nectar is used for honey production (and the fruit is eaten by cardinals, bobwhites, ring-necked pheasants, rose-breasted grosbeaks, white-tailed deer, and gray squirrels). The crape myrtle attracts “beneficial insects” according to the UC Davis Arboretum plant database, but it does not give a list of insect species. Water gum or Tristania laurina provides nectar to honey bees; these bees are common to very common visitors of the water gum flowers. The UC Berkeley Urban Bee Garden project also observes that water gum flowers occasionally attracts small, native bees.

A powerline-centric view of urban tree selection

Image: Pacific Gas & Electric

As mentioned previously the primary limiting factors in planting the right tree in the right place with regards to overhead utility lines is height; trees should be twenty five feet or less in height at maturity. Of the seven species listed by the City of Oakland as “small,” two can attain thirty feet in height: the crape myrtle and the purple leaf plum. Two of the species categorized as “medium” are listed with heights of twenty feet: the bronze loquat (Eriobotrya deflexa) and the Saint Mary magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora ‘Saint Mary’). In general, magnolias are medium-sized trees, but I gather that the Saint Mary variety is typically twenty feet at maturity. The flower of the loquat attracts bees (and birds eat the summer fruit).

The City of Oakland does not list the hawthorn. I have noticed bees buzzing around and landing on hawthorn (Crataegus species) flowers in my Berkeley neighborhood. My casual observation is supported by the UC Berkeley Bee Garden project. Crataegus laevigata attracts five to nine honey bees every three minutes for pollen and nectar, while C. phaenopyrum (Washington hawthorn) attracts five to nine honey bees every three minutes and occasionally attracts small and medium bees for nectar.

Of course, wildlife value is not limited to short stature, showy, flowering trees, and flowers are not the only source of value. Linden trees (Tilia species) attract bees in great numbers according to observations made by the Cornell University Arboretum. The valley oak (Quercus lobata), according to the UC Davis Arboretum plant database, attracts butterflies, beneficial insects, and birds. But, the valley oak does not make a good street tree. Urban sidewalks are not designed to accommodate this large, broad-crowned California native that requires “deep soils where it can tap groundwater.”

A coast live oak in its namesake city, Oakland, California

Photo: Georgia Silvera Seamans, Local Ecology

Actually, the City of Oakland is named for the oaks that used to cover its land area. The coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia) is conspicuously absent from the city’s list of large tree species. This species would require a large growing area and the majority of residential sidewalks in Oakland are six feet wide; a four-foot right of way is required by the Americans with Disabilities Act. To see an urban mature coast live oak (and its optimal growing space), visit Oakland’s City Hall Plaza.

Comments

Interesting stuff, Georgia. I’ve never paid much attention to the height of trees here in the Big Apple or elsewhere. It’s nice to think of birds and insects co-mingling 20 feet above my head. As a matter of fact, it’s hard to think of any real “downside” to short stature tree-lined sidewalks.

Great essay

I appreciate your point to look to broader ecological value. I liked

the specific examples. I could see going even further to suggest

specific species or to look for other ecological value or to provide

examples of trees planted in certain cities or neighborhoods that are

a model for the ecological value.

I’m all for burying power lines. Many an excellent photo has been ruined by a power pole or tangle of wires and transformers. Given that’s not likely to happen any time soon, shorter trees do seem like the answer. The important thing is that there ARE trees and not just a concrete jungle.